Thank you to Lissa Chapman, author of the new book Anne Boleyn in London, for sharing this guest article with us today. You can also read Lissa’s other article “Anne Boleyn: The news on the street”.

Thank you to Lissa Chapman, author of the new book Anne Boleyn in London, for sharing this guest article with us today. You can also read Lissa’s other article “Anne Boleyn: The news on the street”.

Anne Boleyn began to be a non-person around a fortnight before she died. Her household was disbanded before her trial. And in the days between her condemnation and her execution, her husband was partying on the Thames with his wife’s friends, carrying in his pocket and showing to anyone who would read it the manuscript of a play giving his version of her behaviour towards him. Contrary to an assortment of myths, once the guns of the Tower of London announced the death of one queen, Henry VIII had himself rowed to Chelsea to visit the next candidate for what appeared increasingly to be a less than secure position. Already the masons were at work removing the HA initials from public places and replacing them with HJs. And it was an easy matter to alter Anne’s white falcon badge so it would pass for Jane Seymour’s phoenix.

For the next two decades the name of Anne Boleyn was not one to mention in public. It was not until, against huge odds, her daughter Elizabeth survived to become Queen of England in her own right, that Anne’s image was seen again. When the new monarch rode through the streets of her capital city, one of the set pieces of theatre and decoration in her honour featured the life-size figures of both her parents, together for the first time since the one ordered the killing of the other. It is impossible to know exactly what Elizabeth Tudor thought and felt about all this – there is no record of her ever mentioning her mother. But she kept by her a jewelled ring containing her own and Anne’s portrait. And she always favoured her Boleyn relatives.

If Anne’s daughter kept her peace about her mother’s story, others did not. During Elizabeth’s lifetime, there was a deep divide between (Protestant) sympathisers and (Catholic) detractors. The first group, initially including people such as Alexander Aless who remembered Anne Boleyn, wrote of a “most religious” Royal role model. Careful circumlocutions and strategic silences were needed to avoid explicitly blaming the husband of the “most serene Queen” for any part in her fall and death. The second group, including, most famously, Nicholas Sander, competed to outdo each other as to the grotesqueness of the accusations they could make against the mother of the woman whom the Pope had now formally excommunicated and for whose murder any good Catholic would meet with nothing but praise from Rome. For Sander, Anne had been not only a sexually rapacious would-be poisoner but physically deformed into the bargain.

It was not until Dr Gilbert Burnet’s work on the history of the Reformation was published in the 1680s that the first attempt was made to look dispassionately at the story of Anne Boleyn. Burnet concluded that Anne was disposed of for a complicated raft of reasons, and that she was not guilty of any of the charges against her; however, her “very cheerful temper” was considered to have led her beyond the “bounds of exact decency and discretion”, thus making her vulnerable to accusation.

Burnet’s view of the matter was to make generations of constitutional historians highly uncomfortable, as they needed to think that the massed ranks of the House of Lords would not, could not, have condemned an anointed Queen without persuasive evidence. It therefore became accepted that there “must” have been witness statements against Anne that had vanished or been destroyed, and that she therefore was probably guilty, at least of adultery. Writing in 1884, Paul Friedmann, although admitting that there was nothing in the record that proved her guilty of anything, stated that he was “by no means convinced” of her innocence. And Friedmann also went on record as believing that Anne Boleyn was responsible for exacerbating, if not causing, most of the less pleasant aspects of Henry VIII’s character. This was, however, far from being the accepted interpretation at this time. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Agnes Strickland was researching and writing her “History of the Queens of England”, which interprets Anne’s character very differently. Significantly, Strickland regards Anne Boleyn as a political player in her own right, ruled by ambition and not romantic love. Some male writers of the time found the idea of a woman having agency an impossible one, and responded to these suggestions with derision.

Meanwhile, outside the covers of academic publications, Anne was appearing on stage as a wronged and tragic operatic heroine in Donizetti’s “Anne Bolena” and in at least two successful productions in the London theatre. And she shared with the equally ill-fated Lady Jane Grey the distinction of being what must have been the favourite subject for any artist looking for a historical, but non-military, theme. The Annes of these creations are invariably pretty, usually delicate-looking, evidently passive, riven by conscience, and suspiciously nineteenth-century looking about the hair and corsetry. With the invention of cinema it was not to be long before the first film featuring Anne Boleyn as a character was made, and since its release in 1922 hardly a year has gone by without an addition to the genre, whether she is the protagonist as in “Anne of A Thousand Days” or a secondary character as in “A Man for All Seasons”. Anne is invariably portrayed by an actress of great beauty.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, it is rare for a day to pass without someone in the long lines of tourists waiting to go into the Tower of London being heard singing a line or two of the music hall song “With Her Head Tucked Underneath Her Arm…..” There are Anne Boleyn conferences, walks, dvds, innumerable novels, plays and TV documentaries. At the last count there were over 80 Twitter accounts bearing some variation of her name. Historians re-evaluate, and frequently squabble over, the evidence about her, yet again. But, as with the Victorian corsetry, we are constantly remaking her character to suit our own time and taste. Short of a shock discovery of letters in an archive or attic we are unlikely to be able to come to any firmer conclusions about the woman whose bones rest in the Tower and whose living face we think we would recognise.

Lissa Chapman is a theatre director, writer and historian. She is joint founder, with Jay Venn, and artistic director of Clio’s Company, which specialises in researching, writing and staging site-specific theatre, particularly in the London area, and has worked in a wide variety of contexts, from the Tower of London and a variety of cathedrals, stately homes and cathedrals to Kew Gardens and an historic tidal mill, by way of a stretch of canal towpath and the odd damp field. Two productions have been set in the London of Anne Boleyn’s day, and in 2013 the company were chosen to take part in the Lord Mayor’s Show, for which they researched and recreated part of Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession. After walking through London in the pouring rain in the company of eighty nine-year-olds, singing one of the coronation songs for what was probably its first performance since 1533, it was probably inevitable that the research became a book.

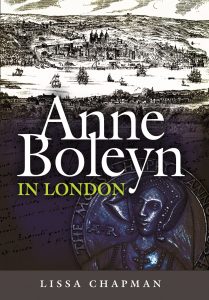

Lissa’s book, Anne Boleyn in London

Romantic victim? Ruthless other woman? Innocent pawn? Religious reformer? Fool, flirt and adulteress? Politician? Witch? During her life, Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s ill-fated second queen, was internationally famous – or notorious; today, she still attracts passionate adherents and furious detractors.

Romantic victim? Ruthless other woman? Innocent pawn? Religious reformer? Fool, flirt and adulteress? Politician? Witch? During her life, Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s ill-fated second queen, was internationally famous – or notorious; today, she still attracts passionate adherents and furious detractors.

It was in London that most of the drama of Anne Boleyn’s life and death was played out – most famously, in the Tower of London, the scene of her coronation celebrations, of her trial and execution, and where her body lies buried. Londoners, like everyone else, clearly had strong feelings about her, and in her few years as a public figure Anne Boleyn was influential as a patron of the arts and of French taste, as the centre of a religious and intellectual circle, and for her purchasing power, both directly and as a leader of fashion. It was primarily to London, beyond the immediate circle of the court, that her carefully ‘spun’ image as queen was directed during the public celebrations surrounding her coronation.

In the centuries since Anne Boleyn’s death, her reputation has expanded to give her an almost mythical status in London, inspiring everything from pub names to music hall songs, and novels to merchandise including pin cushions with removable heads. And now there is a thriving online community surrounding her – there are over fifty Twitter accounts using some version of her name. This book looks at the evidence both for the effect London and its people had on the course of Anne Boleyn’s life and death, and the effects she had, and continues to have, on them.

Hardcover: 248 pages

Publisher: Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1473843618

ISBN-13: 978-1473843615

Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon.com and Amazon UK.

Images: Photo of 30 St Mary Axe, known as “The Gherkin”, with Anne Boleyn’s falcon badge by Lissa Chapman; Photo of the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula, at the Tower of London, by Tim Ridgway.