Today we have a special treat – a guest article on Anne Boleyn from Alison Weir, historian and author of “The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn”, “The Six Wives of Henry VIII” and many other works of historical fiction and non-fiction. Thank you so much, Alison for sharing this article with us.

Anne Boleyn: The Enchantments of Romance

by Alison Weir

It is hard to credit that an English queen could become a modern celebrity nearly five centuries after her death, but in recent years, Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII, has become the subject of ‘a fast-growing cul’, according to Howard Brenton, the author of a new play about Anne that won rave reviews – and deservedly so – at Shakespeare’s Globe this year. From the anonymous person who, every year, on the anniversary of Anne`s execution, arranges for flowers to be placed on her supposed grave in the Tower of London, to the ‘Anne Boleyn lovers’ who regularly post on Yahoo Group sites that amount to Anne Boleyn fan clubs, the posthumous charisma of this most controversial of queens intrigues and fascinates.

In recent years, legions of historical novelists have fed this fascination, serious historians – myself included – have endlessly debated every aspect of Anne Boleyn’s life, and there has been a stampede by film makers eager to cash in on the public’s seemingly insatiable appetite for all things Anne. The question is, why this interest?

The answer lies partly in Anne’s own story, one of the most dramatic – and tragic – in English history. She was a woman who lived on the edge for much of her adult life. Well-born but not conventionally beautiful, at twenty-one, she arrived at the English court after spending seven years in France, and her French manners, her stylish dress and her wit and charm made her an immediate success. By 1526, Henry VIII had fallen passionately in love with her, and the following year he resolved to set aside his chaste and devoted wife, Katherine of Aragon, who had borne him no son to succeed him, and marry Anne. There followed six long years of frustration, with Anne refusing to become his mistress in anything but the courtly sense, and the Pope prevaricating over granting an annulment.

In the end, a disillusioned Henry broke with Rome, declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, and, in 1533, had his union with Katherine declared invalid, and his secret marriage to Anne proclaimed lawful. Having discovered that Anne was pregnant, he had not waited for the formalities.

But Anne’s child, much heralded as the long-awaited male heir, turned out to be a girl, Elizabeth. This was a cataclysmic disappointment, for it had not yet been proved that a woman could rule successfully, as Elizabeth later did, and it was seen as against natural and divine law for a woman to wield dominion over men.

Anne had always held considerable influence over Henry. An evangelical who wanted the Catholic Church reformed from within, she helped to open the King’s eyes to new ideas, although neither she nor Henry ever embraced the new Lutheran doctrines. During the three years that their marriage lasted, Anne continued to be influential, but her power was increasingly undermined. She had found it difficult to make the transition from a mistress with the upper hand to the submissive wife that Henry, a conventional husband, now expected her to be, and her tantrums sorely tried him, driving him to seek solace in other beds, while telling her to ‘shut her eyes and endure as more worthy persons had done’.

Anne’s next three pregnancies ended in miscarriages, which laid her open to the machinations of her enemies, who were legion, not only at court, but throughout the country, where she was widely regarded as the ‘goggle-eyed wh*re’ who had displaced the good Queen Katherine. In the end, even the opposing factions at court united to bring Anne down, building a case on her flirtatious nature and the King’s obsessive fear of treason.

In May 1536, Anne was committed to the Tower of London. Found guilty of criminal intercourse with five men, one her own brother, and of plotting Henry VIII’s assassination, she was sentenced to death. She met her end with commendable courage, kneeling upright to be beheaded by a French swordsman in the presence of a thousand witnesses.

She left behind her an enduring mystery. Had she been guilty, or had she died an innocent woman? ‘If any will meddle with my cause,’ she had said on the scaffold, ‘I require them to judge the best.’ Many since have done just that, reaching conclusions that only add to the debate; but the enigma remains. Anne has become a romantic figure in the widest sense. It is hard to get beyond that brave and tragic figure on the scaffold to the woman who had been the scandal of Christendom and the catalyst for the English Reformation.

She left behind her an enduring mystery. Had she been guilty, or had she died an innocent woman? ‘If any will meddle with my cause,’ she had said on the scaffold, ‘I require them to judge the best.’ Many since have done just that, reaching conclusions that only add to the debate; but the enigma remains. Anne has become a romantic figure in the widest sense. It is hard to get beyond that brave and tragic figure on the scaffold to the woman who had been the scandal of Christendom and the catalyst for the English Reformation.

Given Anne’s story, and the mystery that surrounds her, is it surprising that, for centuries, she has inspired an enduring fascination? For the truth is that interest in Anne is no new thing. As an early biographer, Agnes Strickland, wrote in 1851: ‘There is no name in the annals of female royalty over which the enchantments of romance have cast such bewildering spells as that of Anne Boleyn.’ Queen Victoria was under such a spell, and it is thanks to her that a memorial marks the scaffold site on Tower Green, even if it is in the wrong place. One has only to search for legends and ghost stories relating to Anne to find that she has long been enshrined in English folklore.

Today, the regular misrepresentation of her in films and novels, and on the internet, ensures that myths about her are still propagated, like urban legends, and become accepted as fact. For example, it is often said that Anne was accused of witchcraft. That’s a myth. The report that the King said he had been seduced into marriage by sorcery comes fourth-hand from her enemies, and there is no mention of witchcraft in the indictment against her.

In the aftermath of her execution, and throughout the reigns of Henry VIII’s successors, Edward VI and Mary I, Anne’s guilt appears to have been accepted by most people, and her name was evidently taboo at court. But when her daughter Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558, efforts were immediately made to rehabilitate Anne’s memory. In a pageant staged for the Queen’s coronation, figures of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn were shown enthroned together for the first time in twenty-four years.

Writers such as the martyrologist John Foxe could now write sympathetically of Anne as the victim of others’ malice. Her good works were publicised and lauded, more than they had ever been in her lifetime, while the vindictiveness she had shown to her rivals, Katherine of Aragon and her daughter Mary, was conveniently forgotten.

In Catholic Europe, Anne had always been vilified as a ‘Jezebel’ and a ‘public strumpet’ who had received her just punishment, a view that still informs the work of some Catholic historians. Anne was also blamed for the English Reformation. In 1585, an exiled English priest, Nicholas Sander, in a treatise that became the standard account of the Reformation for Catholics, mounted a savage attack on her, repeating all manner of calumnies and even claiming that she was Henry VIII’s bastard daughter.

Sander’s account provoked outrage in England from generations of Protestant historians. For them, Anne was a saintly queen who had done much to further true religion in England. ‘Was not Queen Anne, the mother of the Blessed Woman, the chief, first and only cause of banishing the beast of Rome with all his beggarly baggage?’ asked one, ignoring the fact that Anne had died an orthodox Catholic; while George Wyatt, the grandson of the poet, Thomas Wyatt, one of Anne’s early admirers, wrote an unpublished memorial of her to refute Sander’s allegations. Based on a lifetime’s research, and possibly written at the behest of Queen Elizabeth herself, it concluded: ‘This princely lady was elect of God.’

That remained the view in England up until the romantic era of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In 1791, Jane Austen bewailed Anne’s unmerited fate, and wrote of Henry VIII as a vile fornicator and sadist. In 1830, Anne featured in Donizetti’s opera, Anna Bolena, in which she was again portrayed as tragic victim. She featured in romantic paintings, such as ‘Anne Boleyn in the Tower’ by Edward Cibot (1835).

Serious historical research on Anne Boleyn had begun in 1720, when antiquarians first started to collate contemporary documents, but it was not until the late nineteenth century that historians began to edit and publish the wealth of source material stored in archives, and thus gradually enriched people’s knowledge of the Tudor period. Prior to that, history’s view of Anne Boleyn had been relatively uninformed and subjective, underpinned by Victorian morality. It was not until 1884 that Paul Friedmann, Anne’s greatest biographer before Eric Ives, debunked many of the romantic myths about her and portrayed her as a scheming adventuress.

As attitudes towards women changed through the twentieth century, so did historians’ assessments of Anne Boleyn. The emphasis used to be more on her relationship with Henry VIII than her political significance. J. D. Mackie, writing his definitive The Earlier Tudors for the Oxford History of England in 1950, pointed out the ‘essential error’ in representing the King’s passion for Anne as the origin of the Reformation. In 1968, John Scarisbrick opined that ‘the divorce was due to more than a man`s lust for a woman. It was politically expedient and dynastically urgent’.

Today, in a post-feminist, politically correct society, Anne’s influence is seen as far greater. According to Diarmaid MacCulloch, ‘Anne triggered the Reformation’. Eric Ives has portrayed her as a both a staunch religious reformer and a femme fatale, while for David Starkey, she is ‘a brutal and effective politician’. As women increasingly come to regard Anne as a romantic figure, the Princess Diana of the Tudor age, and a tragic fashion icon, men tend to emphasise the strengths in her that appeal to the modern world, portraying her as a combination of Hillary Clinton and Carla Bruni. Howard Brenton’s play draws largely but innovatively on fashionable interpretations of a very modern Anne.

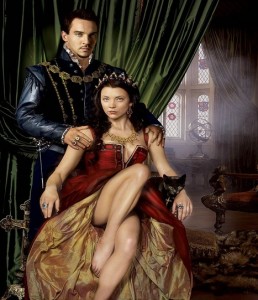

The works of serious historians cannot account for the boom in the Anne Boleyn industry in recent years. I would put that down to two landmarks in Tudor popular culture: the publication, in 2000, of Philippa Gregory’s novel, The Other Boleyn Girl, which resurrected the traditional historical novel from the doldrums in which it had languished for thirty years, and gave rise to two films and a predictable avalanche of copycat novels; and the highly successful television series, The Tudors.

The last comparable flowering of interest in Anne Boleyn came in 1966-70, in the wake of two films, A Man for All Seasons (1966), in which Vanessa Redgrave gave a seductive, evocative cameo appearance as Anne; and Anne of the Thousand Days, a romanticised epic starring Genvieve Bujold. Following this, the BBC produced an excellent cycle of televised plays, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, in which Keith Michell played what, for many people, remains the definitive Henry. Back then, historical novels representing Anne as tragic, innocent victim, such as those by Margaret Campbell Barnes and Jean Plaidy, had been popular for years. The T.V. series inspired many more, but predictably the genre soon became debased and, by the mid-1970s, had gone out of fashion.

The modern obsession with Anne Boleyn shows no sign of abating, and yet what feeds it – novels, filmed dramas, lightweight history books, and dedicated websites and blogs – is often far removed from the historical reality. Anne has become idealised as a historical celebrity, often portrayed as young and beautiful. People define her, more than ever, by her sexuality, as is made explicit in The Tudors. For many, she is the ultimate victim. As a historian, much of this is of concern to me – although I understand the fascination.

My own interest in Anne was born when I was fourteen and read a trashy novel about her that sent me scurrying in search of history books in order to find out the truth; and I’ve been searching for it ever since, over more than four decades spent studying Anne and the Tudor dynasty. For me, the fascination lies in the fact that her story is so dramatic. You couldn’t make it up, which is why I see red when novelists and film makers distort the facts! It’s the enigmas that keep drawing me back, intrigued, to the point where my love of history started – from the romance of Henry’s courtship of Anne, to those terrible seventeen days in the Tower. In my view, Anne Boleyn’s historical importance stems not so much from her influence over Henry VIII in regard to religious reform, because other factors were at play there; it lies, rather, in the fact that she gave England arguably its greatest monarch, Elizabeth I.

Well, I wrote a comment but I don’t think it came through as my computer did a weird thing. So, I’ll make it again!

Thank you, Alison Weir, for this wonderful article. I, too, became enchanted with Anne Boleyn at an early age (15) and have continued my interest for all these years. Your own work has been wonderful in giving me information and I thank you for it! I have well over 100 books about Anne and Elizabeth and keep getting more. Anne is always just out of reach, just beyond knowing–tantalizing. She is part-victim, part-vixen and when I was young, I admired her power over Henry. It seems as long as she was being pursued, she held the reins of power but once she became the wife, the game was up. There’s something of the universal female experience in her story, only her tale is writ LARGE. Anyway, thanks for a great article!

Great article!

Thank you for the article Ms. Weir. I first read about Elizabeth, then Anne. I have read the history of many of the Kings and Queens of England, and I love them all,, but I find I keep returning to the Tudors. Their story is most compelling. Anne’s most of all.

I thank you for giving me so many pleasant hours reading about their lives.

I first became aware of the Tudors when I was on a break at work. I was working at the international terminal (Tom Bradley) at LAX and walked over to the book the store. I was bored as I had just finished a book and then I saw a book titled ‘Innocent Traitor’ which was about Lady Jane Grey. On the cover was a girl in a 16th century style dress and I burned straight through that book! My sister then read the book after me and that is when the madness began! We were so thrilled when we saw that there was also this new TV series about the Tudors (which we now pick apart and say that was true that wasn’t… lol) and began buying up a lot of different books. My sister and I absolutely HATE Phillipa Gregory’s books!! ughhh somehow they always end in incest…

Anyways, thanks Allison! Love your books and this article! 🙂

Thanks Allison for an interesting article. The history of how Anne has been perceived through the centuries is almost as interesting as her life itself. She seems to be all things to all people.

There seems to be a pattern here…. I too read a novel about Anne Boleyn (Margaret Campbell Barnes’ ‘Brief Gaudy Hour’) when I was 13 or 14 and I was hooked. I read all the historical romances I could find about her and when the library ran out, I picked up a biography. That was the beginning of a depp and abiding interest in history. I read about all periods but always keep coming back to Anne and Henry and Elizabeth.

Talking about how Anne Boleyn has been perceived in Europe, I once came across a book by Saccheverall Sitwell about his travels in Spain in the (I think)1920s before the civil war. He describes a great fiesta where ancient ‘gigantones’ – giant papier-mache puppets – were brought out of Toledo cathedral and paraded around the streets and made to act out farces. One of them, a grotesque, ugly female, went by the name of Ana Bolina.

He does not comment on this at all, so I’m not sure if he realised the significance, but it amazed me to think that the Spanish people were still poking fun at her after so many centuries and I wondered whether they knew who she was.

Maybe it’s a bit like us in the UK burning Guy Fawkes every year.

Sadly, the gigantones are now gone and that link with Spanish and British history has now died away.

Thank you Alison for your article!

I also became interested in Anne for the first time when I was 14 and since then my interest has grown. I think she was a unique, intelligent and strong woman with the virtues and flaws of all passionate human beings. Thank God all the nasty myths about her are being brought down thanks to sites like TheAnneBoleynFiles and true historical biographies.

Thank you for the great article, Miss Weir!

I first became aware of Anne when I watched “The Six Wives of Henry VIII” on Masterpiece Theatre with my parents when I was 10 years old. My mother bought me a few paperback novels about Anne (“Anne Boleyn” by Margaret Heys, “The Rose of Hever” by Maureen Peters, and “Brief Gaudy Hour” by Margaret Campbell Barnes), and this inspired me to read all the biographies of Anne I could get my hands on. While I enjoyed all the versions of Anne on the screen, my definitive Anne is the one played by Dorothy Tutin. Loved those dark eyes, and her intelligence, courage and fire!

Again, many thanks for your article. 🙂

Thanks Miss Weir for the wonderful article!

Its interesting to think how Anne’s fascination has endured over the years and how every generation seems to view her in a different light. I guess people love a good mystery and Anne’s is a very hard character to try to pin down! I’ve been interested in Anne since I was ten, so that’s nearly twenty-five years now, and sometimes it seems the more I read about her the more elusive she becomes!

Anyway, thanks again for the article

Awesome article !!!! I am obsessed with Anne , I want history to right a wrong , and give her the proper acknowledgement , as the Queen she was .

I arrive into London early on May 19, 2011 and I am going to make a point of going to the Tower and seeing for myself these flowers that the mystery person leaves at her grave if they are allowed to remain there…..this will be a special treat for me….

This Queen haunts me, as well as, The Tudors all…..so many truths need to be brought to light regarding this family…..

Tis a great article and I can only hope my comments have finally reached their destination in order to tell you, job well done!

Great article. I work in a library and get a hold of any book, be it fiction or non-fiction about the Tudors. I first became enthralled with them when seeing the Six Wives of Henry VIII with Keith Michell. He was Henry personified. Aging as he did in looks and temperament was amazing. I could not stomach the Tudors on HBO. Though a good actor, Henry did not look anything like Jonathan Rhys-Myers and every wife was a “glamour girl.” So I took a pass on it. Would love to see someone do a series of Mary, Queen of Scots sometime. She too had quite the life.

Bella, I think you make a good point about finding Anne to be such an elusive character. I had not realized that so many writers had such differing viewpoints of her and how much of the information was untrue. It reminds me of the three books I read about Julius Caesar. It was like reading about three different men.

13, and just discovered Anne and the Tudors last month. I have scoured my library over for all things Anne. I have read Eric Ives’ book, and absolutely loved this article. I ” DISCOVERED ” Anne when I read a really great novel by Margart George , the auto bio of Henry 8, last summer and Anne was so tragic!!!!!!!!! Love this site !!

Wait……………… sorry! I first heard of Anne last summer, but then I was studying Cleopatra and Ann e Frank but this last month I really got serious about Anne and read biography , after biography, to where ny interest expanded to all yhe Tudors, especially Anne.

Ms. Weir, thank you, not only for this article, but for your many biographies of British historical characters. I believe I have read every book you’ve written.

I see Anne as a tragic figure, used by the men around her for their own ends: her father, her brother, her husband. As others have commented, the truth will never be known, and endless myths will be spun.

I wonder how much the genetic factor(s) that led to the deaths of both Prince Arthur and Edward VI may have affected the miscarriages/infant deaths of Henry VIII’s children (sons in particular), regardless of who their mother was. Also, the fact that none of Henry’s last three queens even became pregnant at all — do we know if there was a congenital weakness that may have played a part in this? Is there any medical knowledge that anyone has that may shed light on this question?

Claire, thank you for this site: though I’ve only discovered it recently, I find it to be thoughtful and well written. I see that you are most interested in the truth, without the filters of today’s attitudes, and I appreciate your efforts very much.

Thank you, Jani, I’m so glad you found my site and that you’re enjoying the articles.