On this day in history, Thursday the 12th September 1555, the trial of Archbishop Cranmer began in the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin at Oxford. He was accused of two offences, or doctrinal errors: repudiating papal authority and denying transubstantiation.

On this day in history, Thursday the 12th September 1555, the trial of Archbishop Cranmer began in the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin at Oxford. He was accused of two offences, or doctrinal errors: repudiating papal authority and denying transubstantiation.

A ten foot high scaffold, decorated with cloth of state, had been erected in the eastern end of the church in front of the high altar and it was on this scaffold that James Brooks, the Bishop of Gloucester and representative of the Pope, sat. Below him, sat Dr Martin and Dr Storey, Queen Mary I’s commissioners (or proctors) and doctors of the law.

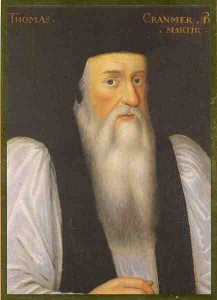

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer was brought into the court. John Foxe describes him as “clothed in a fair black gown, with his hood on both shoulders, such as doctors of divinity in the university use to wear, and in his hand a white staff” and goes on to say that he would not doff his cap to any of the commissioners. One of the commissioners called him forward, saying, “Thomas archbishop of Canterbury! Appear here, and make answer to that shall be laid to thy charge; that is to say, for blasphemy, incontinency, and heresy; and make answer here to the bishop of Gloucester, representing the pope’s person!”, and Cranmer was brought up to the scaffold. Cranmer then doffed his cap and bowed to the Queen’s proctors but did not bow or doff his cap to Brooks. An offended Brooks asked Cranmer why he did not show him respect and Cranmer replied “that he had once taken a solemn oath, never to consent to the admitting of the bishop of Rome’s authority into this realm of England again; that he had done it advisedly, and meant by God’s grace to keep it; and therefore would commit nothing either by sign or token which might argue his consent to the receiving of the same; and so he desired the said bishop to judge of him.”

After Brooks and Martin had given their ‘orations’, Cranmer replied that he did not recognise or acknowledge this court:-

“My lord, I do not acknowledge this session of yours, nor yet you, my mislawful judge; neither would I have appeared this day before you, but that I was brought hither as a prisoner. And therefore I openly here renounce you as my judge, protesting that my meaning is not to make any answer, as in a lawful judgment, (for then would I be silent,) but only for that I am bound in conscience to answer every man of that hope which I have in Jesus Christ, by the counsel of St. Peter; and lest by my silence many of those who are weak, here present, might be offended. And so I desire that my answers may be accepted as extra judicialia.”

Then he knelt, “both knees towards the west”, and recited the Lord’s Prayer and then rose and recited the Creed. According to John Foxe, Martin asked Cranmer who he thought was “supreme head of the church of England”, to which Cranmer replied, “Christ is head of this member, as he is of the whole body of the universal church”. When Martin pushed him further, asking why he had then made Henry VIII the supreme head, Cranmer stated, “Yea, of all the people of England, as well ecclesiastical as temporal” and went on to say, “for Christ only is the head of his church, and of the faith and religion of the same. The king is head and governor of his people, which are the visible church.” He explained that “there was never other thing meant” by the King’s title.

After the commission had heard from Cranmer, they ordered him to appear at Rome “within fourscore days” to answer to the Pope. Cranmer agreed to do this and was then taken back to his prison. Cranmer was never taken to Rome but his fate was decided there on the 4th December 1555. The Pope stripped him of his office of archbishop and gave the secular authorities permission to sentence him. Cranmer’s friends and colleagues, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, who were also tried for heresy on the 12th September 1555, had already been burned at the stake on the 16th October and now Cranmer desperately tried to save himself by recanting. Between the end of January and mid February 1556, Cranmer made four recantations, submitting himself to the authority of the monarch and recognising the Pope as the head of the church, but despite this his priesthood was taken from him and his execution was set for the 7th March. Cranmer quickly made a fifth recantation in which he stated that he fully accepted Catholic theology and that there was no salvation outside of the Catholic Church, and announced that he was happy to return to the Catholic fold. This recantation and statement of faith really should have led to him being absolved but although his execution was postponed another date was soon set. This postponement simply allowed a final, public recantation to be organised at University Church, Oxford.

On the 21st March, the day of his execution, Thomas Cranmer was taken to the church to recant in front of the waiting crowd. After opening with the expected prayer and exhortation to obey the King and Queen, Cranmer suddenly changed tack and instead of recanting he actually renounced his recantations:-

“And now I come to the great thing which so much troubleth my conscience, more than any thing that ever I did or said in my whole life, and that is the setting abroad of a writing contrary to the truth; which now I here renounce and refuse, as things written with my hand contrary to the truth which I thought in my heart, and written for fear of death, and to save my life if it might be; and that is, all such bills and papers which I have written or signed with my hand since my degradation, wherein I have written many things untrue. And forasmuch as my hand hath offended, writing contrary to my heart, therefore my hand shall first be punished; for when I come to the fire, it shall be first burned. As for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy and antichrist, with all his false doctrine. As for the sacrament, I believe as I have taught in my book against the bishop of Winchester, which my book teacheth so true a doctrine of the sacrament, that it shall stand at the last day before the judgment of God, where the papistical doctrine contrary thereto shall be ashamed to shew her face.”

He was quickly pulled out of the church and led to the stake, where he knelt and prayed. John Foxe describes his execution:-

“Then was an iron chain tied about Cranmer, whom when they perceived to be more steadfast than that he could be moved from his sentence, they commanded the fire to be set unto him. And when the wood was kindled and the fire began to burn near him, stretching out his arm, he put his right hand into the flame, which he held so steadfast and unmovable, (saving that once with the same hand he wiped his face,) that all men might see his hand burned before his body was touched. His body did so abide the burning of the flame with such constancy and steadfastness, that standing always in one place without moving his body, he seemed to move no more than the stake to which he was bound; his eyes were lifted up into heaven, and oftentimes he repeated “his unworthy right hand,” so long as his voice would suffer him; and using often the words of Stephen,” Lord Jesus, receive my spirit,” in the greatness of the flames he gave up the ghost, in the sixty-seventh year of his age.”

You can read more about Cranmer’s execution, including an eye witness account, in my article “The Execution of Thomas Cranmer”.

Notes and Sources

- “THE LIFE, STATE, AND MARTYRDOM OF THE REVEREND PASTOR AND PRELATE, THOMAS CRANMER, ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY” from “Actes and Monuments” or “Foxe’s Book of Martyrs”, John Foxe, 1889 edition.

I have read many times that Cranmer was a weak and cowardly man. I have never thought that. To me he seemed a decent honest and principled person. He was the only one who tried to plead for Anne Boleyn on hearing of her arrest. That took guts!

His end was truly horrific, yet he bore it with with such bravery and dignity that it astounds us even now, hundreds of years later.

God rest you Thomas Cranmer, a brave and noble soul.

I agree with you, Gillian. When I read Cranmer’s story it makes me think of Peter the apostle who denied Christ three times and yet went on to be the rock on which the Church was built. Cranmer must have been terrified and I really can’t blame him or judge him for trying to save himself but he repented of this’weakness’ and went to his death with courage and dignity. He was a brilliant man who did not deserve his brutal end.

Thomas Cranmer was the rock on which church was built?

I didn’t say that, I said that Peter was, although today’s Church of England owes much to Cranmer and his work on the Book of Common Prayer. I was saying that his recantations followed by his strong sermon taking back his recantations and professing his faith remind me of Peter who also betrayed God and his faith but then became an important evangelist.

A tragedy, for all concerned (IMO). Can’t help wondering what would have happened if Mary had him beheaded for treason (due to his part in the Jane Grey matter), instead of burned for heresy.

I think that’s a great analogy, Claire. I think he was very much like Peter. I like Cranmer because he was human, he made mistakes, he had fears (and who wouldn’t have?) but in the end, like Peter, he was true to his principles and suffered horrifically. The image of the hand in the fire is one that would be hard to ever forget. His work is still important nearly 500 years later.

Hi Sandra,

I’ve heard people criticise Cranmer for his recantations but as much as I’d like to think that I’d stay strong in my faith I just can’t say how I’d act when faced with the prospect of being burned at the stake. Yes, the image of him putting his hand in the fire to punish it is one that really has an impact on me and must have had an impact on those there at the scene. The stories of Cranmer, Ridley, Latimer, Anne Askew and other religious martyrs are shocking but incredible, they were so brave and faithful.

Recantation SHOULD have saved him, but I think Mary might have wanted to extract a pound of flesh, because Cranmer’s rise had been helped by Anne, and he was the highest ranking of Anne’s supporters that was left standing in the wake of her execution.

Plus, Cranmer had been the one to rule Henry and Katharine’s marriage null and void, which just added to the humiliation of Mary’s own bastardy.

A pity that Cranmer was the one in the flames, when it was Henry who had had the power all along in the “Great Matter” and Henry was the one behind the horrific, disgraceful treatment of both Katharine and Mary.

I have always thought Cramner was one of the more gentler, feeling people of those dog eat dog times, even though he was in the pay of a hard to please King, and had to do things that would have been against his better judgement and believes in fear of retribution, he did stick his neck out on occasions, speaking in favour of Anne, and trying to guide Catherine Howard in her dilema, were two. He recanted from pure fear, a normal human reaction, religious or not, not everyone can walk easily, no matter how strong their conviction to such a horrific death. But in the end he found the strength to be true to himself, and he met his execution with a strong admirable, bravery.

IMO Cramner could have recanted a thousand times over, crawled on hands and knees from England to Rome, and it still would have come to the same ending for him. Mary wanted his execution out of revenge for the part he played in Henry’s divorce and marriage to Anne, religious differences aside, nothing could have altered her mind and as wrong as it seems, that was also a natural human reaction to the pain, neglect and humiliation she saw her mother suffer, and herself too.

I think Mary inherited that bloodymined revenge trait from her father, as we know he cut down many in his time from churchmen to wives.

In the end Cramner died as he lived, a man with a quiet inner strength, that in the main, went un-noticed by many of his peers past and present.

How he managed to remain unflinching in his execution is inconceivable. I hope he found in his next life that was sorely lacking in the one he left behind.

I think that Mary was far from bloodyminded and you do not inherit ideas about how to treat people from anyone; you learn them from your environment and the example in life set you or your experiences. Mary was actually described by people who knew her as fair minded and kind. She was not personally cruel and she was a person who actually struggled with acting out of justice to arrange an execution. She did not want to execute Jane Grey for example and had to be forced into that decision as Jane would have been the sight of plots against her. If Mary inherited this trait then so did Elizabeth as her cruelty to the hundreds of Catholics killed was far worse.

Mary killed hundreds of Protestants burning men women and children if they would not recant how do you think she got the nickname Bloody Mary, Elizabeth did put people in the tower but mainly the Catholics tried to rebel against her rule committing treason which is punishable by death remember the Queen of Scots and some of her own Catholic noblemen plotting to overthrow the crown

They were not rebels! Many of those executed were killed for just being a Catholic priest or helping a Catholic priest. Our religion was outlawed. The Northern Rebellion was the same as the Pilgrimage of Grace and yes some noblemen tried to replace Elizabeth with Mary Queen of Scots but most of these people were just minding their own business. Campion, Glyn Jones, Davies, and thousands of others were either imprisoned or executed just for the innocent practice of the faith. You will not have heard of the latter two: they are Welsh priests who published the first book in Welsh; a list or morals and prayers; they were found in a cave and were attending to the needs of the local poor people. They and six others were hung drawn and quartered. Crime of the other six; refusing to give these men up to the authorities. Margaret Clitherow and Joan Huddleton, two women crushed to death for refusing to plea; a crime if you did not say guilty or innocent or recongise the court; Saint Philip Howard, a handsome nobleman put in the Tower and who died of disease and hunger after three years neglect; and hundreds others who were killed as it was called treason to be a practising Catholic or to minister to Catholics and this was being a priest. Imagine if your local priests were arrested today and Catholic families were rounded up and fined or put in prison just for being Catholics. There would be outrage. Open your eyes to the truth. There may have been a few people who chose to engage in plots against Elizabeth and just about every other monarch about but they felt they had a cause. The majority were just ordinary people trying to keep the faith alive. Many others were not put in prision but fined for not attending the forced on them official church. Every monarch decided their church was correct and it was a crime against state to be something different. There were also others who felt forced to avoid ruin by conforming. If not our faith would not have survived.

As for the hysterical claim that Mary killed hundreds of Protestants men women and children who would not recant: that is utter rubbish. Being an adult was considered to be 15 plus in those days. No children were burnt by Mary or her government and we now know that some rubbish stories by Foxe about boys being forced to recant is utter rubbish. Experts have expsosed some of these tales as just that tales. Women were executed the same as men as adults and had been since the rule of Henry VIII. Few women were executed in the rule of the Plantagenets as they thought it to be against the ancient code of chivilary. The Tudors had no such notions and women were considered to be capable of being obstinate as well as men. It was the most severe cases that were executed and Mary did not do it out of cruelty but it was necessary to bring back the heresy laws and all monarchs did the same thing. We are too wooly minded to accept that all monarchs had high ideals that led to them seeing heresy as a state crime and a danger. We think of toleration but no such notions existed then. She did not get the nickname Bloody Mary until the 19th century and this is again because Protestants write the history. I could use the same phrase Bloody Elizabeth or Bloody Henry but it would not go down very well today. The total figure killed by Mary for heresy is 263 and many of these are now being questioned as some were involved in treason plots to put the Greys and others on the throne. It is the same argument.

No-one deserves such a horrible death for their faith and it stands out because it was a short time. There is evidence though to suggest that her policy was a successful one and more and more people were coming round to her settlement. The majority of the country was still Catholic and you will find that it was only in the Protestant heartlands in the south east that her policy was not accepted. Instead of making hysterical remarks try reading more about both reigns as I have done and then you will have a balanced view of both of them. Bess did a lot of good stuff but she also was as ruthless as the rest of the Tudors. The reason we do not have this problem today is that laws were passed to give both faiths freedom, but that was not until 1829 and only with the election of a Catholic MP to the Irish Parliament. There was no choice as he said he would march on London and take his seat: peacefully but he would take up his rights and it was made that he could. Some laws still exist making Catholics second class citizens. Imagine telling the King or Queen you cannot marry or be anything other than Church of England. Catholics cannot hold certain public offices today; and we are still the subject of hysterical outbursts and rubbish such as you have made above.

It is about time the title Bloody Mary was removed from history books as it has no place in a modern society and both Elizabeth and Mary need to be re-evaluated along with the fresh look at Henry VIII. At least I am a realistic person and can accept that several people were wrongly executed for their faith by both Queens, but I am not going to get hysterical about it. It is a fact of history, sad, but we have to just learn to accept it.

Sorry BQ, not only is it unfair to say Elizabeth I executed just as many catholics as Mary did protestants, but its also ridiculously untrue. In the beginning of her reign, Elizabeth practiced a limited form of religious toleration, and Catholics were generally left alone so long as they paid lip service to the Church of England.

However, later in her reign her attitude towards Catholics hardened. This was due to the Pope, Pius V, who in 1570 excommunicated her and declared that anyone who killed Elizabeth was not committing a sin. I don’t know what he was thinking of, because not surprisingly this made things much worse for English Catholics. Elizabeth really had no choice but to take a harsher attitude towards Catholics. This led to further repercussions, as Philip II of Spain threatened her with war.

That being said, I also would like to point out that its common knowledge that Elizabeths catholic executions were very rare. I find it rather disturbing that you’re so dismissive about Mary Is persecutions of sooo many protestants, even justifying it by saying that Elizabeth I persecuted catholics too! Especially since Mary I reigned as queen for only 3&1/2 years, compared to Elizabeths Is 45 year reign! It boggles my mind to think what the catholic death toll would be, had ElizabethI kept up w/MaryIs pace! I think some calculations are in order: for simplicity, let’s just round off the total you give above (200+) to 300 for Marys protestant persecutions. So, 300 in three & a half years averages out to just under 100 a year. Again, for simplicity we’ll just round it off to 100. So, for a true, & fair comparison, ElizabethI would’ve had to persecute at least 100 catholics a year, for every single year of her 45yr reign to be deserving of you, or anyone trying to make this ridiculous comparison you’re trying to force feed us! That’s why MaryI has came to be called, ‘Bloody Mary’, while ElizabethI came to be known for such tollerance! Mary earned that name and reputation, just as Elizabeth earned hers. ElizabethI rescued her people from MaryI as far as I’m concerned. Next time you want to justify what Mary did, by saying, ‘So did Elizabeth!’. . .you need to recognize that for that to be a true & fair statement, ElizabethI would’ve had to have executed at least 4500 catholics! Now do you understand? 🙂

Oh, almost forgot; it’s also rather disturbing how you just gloss over some of the younger younger protestants that were persecutionsed by saying that, in those times 15 was considered an adult. Well, that doesn’t change the fact that a 15 year old is still just a child. Heck, I’ve known quite a few 20 year old that just aren’t mature enough to be considered an adult! Times & attitudes are always changing, and always will be. Times were hard back then. With many mouths to feed parents concentrated on raising kids quickly and marrying them off and on their own to lessen the burden. But, none of that changes the fact that most of us in our teens are still just children, mentally and physically.

I’ve read a whole lot of your posts BQ. And though you do appear to be well read on Tudor history, you seemed to have let your catholic faith bend your attitude quite a bit. I’m neither catholic or protestant, so I’m able to look at all of it less objectively. But, make no mistake, I was exposed to both religeons growing up because my father is catholic, and my mom converted to it about a year or so before I was born. I was forced to go to catholic schools from first through fifth grade. Horrible experience! To this day, I still can’t believe how much meaner those nun teachers were than the public school teachers! So, I’ve very informed about what catholics are all about. Interestingly enough, after quiiting catholic school and starting public school, I became best friends with a girl who happened to be protestant. And her protestant mom, forced her into a private protestant school, as my mom had forced me into the catholic school. I started going to church with her and became familiar with that religeon too, though not nearly as much as my exposer to catholosism.

Anyway, I just think someone telling another poster that they should stop being hysterical, and they should read up more on the subject before posting is kind of funny. Especially, when its so obvious to everyone else how slanted the person who is writing those words opinion is. Maybe you should take your own advice and stop looking at Mary through rose colored (&catholic) glasses.

There is just no comparison between the kind of queens these two half sisters made. One was very wise, very intelligent, and yes, very ruthless. Like you said, they had to be back then. The other older one was very bitter, intelligent, but not so wise, and her bitterness made her vindictive, as well as ruthless. Both were probably very lonely and probably not the happiest of women to be sure. One became a great queen, known for her intelligence & wisdom. The other became a not so great queen who wouldn’t really be known for anything if not for her bloody persecutions of the protestants. Oh, and I have read & researched both queens quite extensively. 🙂

Fao FAB NAY NAY I use the original sources and my posts are based on fact, not myth. You are entitled to your personal opinion but please remember so am I and I am also entitled to say if someone is posting emotionally, just as you seem to be objecting to my Catholic faith. I too have many friends from the many reformed traditions and yes I am well researched in this subject. A child was not a child at 15, fact, that is the problem with this period. We might be more enlightened or think we are but saying someone is a child makes people think about little children, that is all, not young adults. It is misleading, not glossing over. I am entitled to my opinion, I will post as I wish.

FabNayNay

The argument regarding whether Elizabeth I persecuted Catholics is relevant as an illustration of the times. I admire much about Elizabeth, but yes, I have a personal interest in Mary, that has nothing to do with what faith I am. If you have read my posts correctly you will be well aware that they are well reasoned and argued. I appreciate that you may have read something as well but that does not mean you have the right to attack my faith. Elizabeth I did persecute several hundred Catholics, she executed twice as many so called northern rebels than either Henry or Mary, in three days of execution. She caused generations of suffering in Ireland, a process carried on for another 300 years and thousands of people were executed, died in prison or were fined into poverty under her laws. The persecution of heretics across Europe was rife. I don’t justify it as my post says, I just don’t get emotional about it as it was a fact, not a personal attack on one person or another. Now Mary and her government did have a bone to pick with Cranmer, which is why so many people wonder why he was not executed for treason. The key role that he played in the reforms which so many resented plus his importance as a reformation leader, his role in the marriage annulment and several other political agendas is the answer in part. Cranmer himself was a scholar, an intellectual, had great insight, he was not weak as he is sometimes called, his first four recantations are merely signing formal write ups of the crown, his fifth and sixth are more dramatic as is his change of mind. In the end he stood up for what he believed to be true. Fortunately we have moved on form those days, we have learned to know our fellow Christians and not see them as enemies of the state or society. We have learned to live together. This is why I say it is time that the late seventeenth century nickname of Bloody Mary was taken out of history books as there is no place for it today. Mary Tudor has been shown to be a fair ruler, with far more time for rebels and traitors than many other rulers, her reign far less bloody and her policies far more popular than myth suggests. She was just as intelligent and in many ways as wise as Elizabeth, but with the bad luck to have come to the throne late, her tax and social reforms would put many modern governments to shame, she attempted to forgive the same group of traitors twice, only to be betrayed again, she extended and protected trade and large parts of the country approved of her religions policy which included education and evangelism. Mary Tudor was no more Bloody Mary than Henry Viii was Great Harry or Elizabeth Good Queen Bess, all are the product of a well oiled propaganda machine. When you reign for 38 years or 45 you have longer to work on your legend. Fortunately some authors like Linda Porter and Anne Whitelock are prepared to revise those myths.

I can’t help but agree with you BanditQueen.

I love the analogy to Peter, that most human of the disciples. Cranmer did speak up for Anne, the only one we know of to do so. And, in the end, he recanted his recantation with great courage and honesty. I continue to be amazed at how courageous these doomed folks were, most of them at lesat, at the very end. To die with dignity was of great importance and Cranmer certainly did so. As did Anne.

According to Acts and Monuments of the Church, by John Foxe, 9th Edition, 1684 (full compilation of all 4 original versions, with Latin portions also translated into English); Also known as Foxes Book of Martyrs, 1684, Cranmer’s trial officially began on Monday, April 16th, 1554. I’d like to know where your much later edition gets September 12, 1555 from.

Hi Will,

I think you’re referring to the disputation which took place in April 1554, but the actual trial took place in September, with the papal mandate being served on Cranmer on 7th September and the trial starting at the University Church on 12th September. I can’t find the edition that I used for that article but the 1839 edition is the same – “The Acts and Monuments of John Foxe: A New and Complete Edition with a Preliminary Dissertation by Rev. George Townsend Volume VIII. It can be read online on Google Play – https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=qwMXAAAAIAAJ&rdid=book-qwMXAAAAIAAJ&rdot=1 and see p39 and 44.

Hi Claire – right you are! Although it is often called his “first trial” it really was a disputation. Thanks for that!

I am really impressed with your writing skills as neatly as with

the structure in your weblog. Is this a paid subject matter

or did you modify it your self? Anyway keep

up the excellent quality writing, it’s uncommon to

see a great blog like this one today..

The trial of Thomas Cramner, former Archbishop of Canterbury is a strange one in that he could have been tried for treason more easily than heresy. However, he was a unique personin that he was an important and prominent person and churhman who had served under Henry VIII and of course had served under Edward when he forced the Prayer Book reforms on a mostly Catholic population. For Mary’s regiem his recanting would have been a big scalp. His trial was of course public as it would have been and he was taken to a church where a public platform was placed and he was to make any confession or admission or recantation on this platform. You can see still where in the pillars in the church that the platform was hammered into the sides of them. Thomas Cranmer was not a weak man or a coward; he was a human being and he wanted to save his life because he believed that he would be spared.

At first he follows the normal pattern that even important heretics would have followed and admits what he believes to be true. Then for reasons important to himself and to save his life he recants and not only once but five times. He actually recanted and then withdrew his recantation and had to admit it again. He then made a more formal recantation in much more fuller detail. It was repeated two more times because of his importance. It was not just done for the sake of it. It was repeated because Cranmer is so important in the Protestant Church. He is a big fish and the state want to make sure that his recantation is not only recorded, but is sincere and is recorded at the highest level. It was important for it to be repeated for the purposes of the state to fulfill these two demands. Also Cramner had already withdrawn one recantation; the state and the courts want to make sure he does not do so again. If you read his recantations all of them are slightly different and the last three are much more detailed than his initial public one. I believe each of them meets a particular purpose and this explains why there are so many of them and why they are varied.

Now it is important to realise that recantation does not automatically save a person from being executed when they are tried and condemned as a heretic. In some cases that are important and repeated offences; the state may want to make a point. The idea here is to deter other people from following the same path. Executions for heresy were often great religious and public spectacle, especially in Spain when they took part during a public Auto De Fate or Act of Faith. Even those who have recanted, may still be executed. Cranmer is not the only example of someone who was executed from this point of view. As someone who was considered to be a leading heretic by Mary’s government and someone who would influence others he was seen as a constant and present danger to the state. Heresy was not just a religious crime; it was a political one and a social one as well. Cranmer would have been seen as a repeated offender and in a position to encourage heresy in others. He had been a religious and political leader in the reformation and this made him very dangerous in the eyes of the Marian government; he was too dangerous to leave alive; as he may go back on his recantation and lead a plot against Mary or influence others to do the same. So, even though he had recanted he was still executed.

The odd thing about Cranmer’s execution as a recanted heretic is that he was not strangled first. This would have been normal in such cases of recantation of a person to be executed. The mercy would be to strangle them first and then burn their body. We know that this did not happen to Cranmer, as he was alive at the time of his burning. But why? One or two authors have him taking back his recantation at the end and others say it was because he was guilty of other crimes against the state that he had not confessed to or repented of. That high crime of course is high treason!

Mary believed that Cranmer was responsible for the divorce of her mother and father and the declaration of her own bastarization. This was now reversed and Parliament changed those early laws. It erased everything that Cranmer had declared and so made his actions treason. In the eyes of the regiem and Mary in particular Cranmer was personally guilty of plots against her and against her status as a female King appointed by God. Treason was the main reason for still carrying out the sentence of death; but why not use the normal sentence for treason? Because he was already condemend as a heretic and it did not seem necessary to execute him in the full manner of the law for treason. As long as the state saw justice done in this case; Mary was content to have him executed as a heretic. Hanging, drawing and quartering possibly seemed too harsh for a man of his status, although Henry had not worried about this when he carried it out on the church men and women who would not say he was head of the church in England. A mere beheading may have made his alleged crimes seem trivial; so she gave her consent to the traditional death for heresy rather than treason, even though Cranmer was actually condemned for both.

I do not take much notice of all of the gory details and the speaches that these people made while they were burning. It is more likely that they died very quickly and that any movements and automations of joy with arms and so on were simply from the movement and contact of energy from the flames as modern experiments have shown. I also take some of the stories of Cranmer sticking his arm into the flame first as nonsense as he would have been secured fast to the stake and between bundles of wood, and not able to move to place his hand anywhere.

I think it is true to say that Mary was fair minded and kind in general, but I think there is no denying the element of revenge in her actions against Cranmer. Whether inherited or learned, there was a streak of ruthlessness in Mary which manifested itself here. Of course this is necessary for a Queen regnant, but I find the trial and execution of Cranmer as one of the less excusable actions of Mary’s reign. Of course it was much easier for her to blame someone else for her father’s actions against her mother than to admit that actually he was responsible.

That is the saddest thing of all, Lynne, with both Mary and Catherine of Aragon there is an unexplainable denial that Henry is to really blame for their ill treatment; Catherine knows Henry is the one making the decisions and pardons him; but she also sees her former husband as being misled and ill advised and others are to blame; and Mary simply cannot accept that her beloved father would really shut her out of his life. It is at this point if this was now that an army of doctors would line up and tell you that children often do react like this, even to abusive parents. They love their parents unconditionally and want to please them. Mary simply did not accept or believe that her father wanted to shut her out of his life or treat her harshly and looked for others to blame; Anne, Cromwell, Cramner; the Boleyn family, anyone who was willing to encourage Henry this way or to act on his orders. There is certainly the blame game here in her harsh treatment of Cranmer. As you say she has to be ruthless; she is the first Queen in her own right and she has more to prove even than a man would; and she proceeds according to her convictions. Heresy trials and executions as well as actions against Catholics may seem odd to us; but to a Tudor monarch they were simply threats against the social order; the idea of tolerance was alien to them. No-one should die for religious views or social views and the fires are a terrible thing to have; but sad to say; that was how monarchs acted and what most people believed; it is not excusable; but we have to accept it.

BanditQueen, the following is from your post above; “There is certainly the blame game here in her harsh treatment of Cranmer. As you say she has to be ruthless”.

Just wanted to say I do agree w/that statement, and most of what you say about Marys & COAs feelings & attitudes regarding Henrys harsh treatment of them. Neither deserved the treatment they endured, that’s for sure!

It’s not really surprising, considering all the years of feeling his rejection, and then how humiliated she must’ve felt when she found out she’d been declared illegitament by Henry! The agony of being separated from her mother, and never allowed to ever see her again. How helpless she must’ve felt towards the end of her mothers life, knowing her mom was sick, but still not being allowed to see her.

Poor girl! It’s no wonder she became so embittered & vindictive! Cramner didn’t stand a chance once power was in Marys hands! And who can blame her for taking full advantage of that power, and making one of the main people she considered responsible for her mothers downfall, and eventuall death, pay the ultimate price?

I don’t agree that Mary was vindictive, ruthless yes, most monarchs were; Elizabeth could be just as ruthless, dangerously so, jealously so. No Tudor monarch would be argued with. Mary showed remarkable restraint when dealing with the rebels in the first six months of her reign, even pardoned the leaders, only to be threatened by disposition and death by the same lot. Considering what she went through, Mary was wiser and more attentive to counsel than either of her sibblings. Cranmer was the exception not the rule. Heretics were denounced locally, given several opportunities to repent and recant, several let offs, were tried locally, it was only a handful that were state prisoners. In England, at least, they were not tortured. That is a myth. Catholics were charged with treason, not heresy. By the way, Cranmer also condemned people for heresy and blasphemy. The majority of state officials, clergymen, laymen, were in the service of the crown, which after 1529 tried people itself for serious heresy, but by now most had moved back to the parish, although it was the lay authority, the magistrate, not the clergy who sat in the courts. I recommend Linda Porter or Edwards for a balanced view of Mary.

You know I have always found the Mary vs Bloody Mary debate amazing. Considering the death toll of Henry VIII and judicial killings he practiced wouldn’t he have been more deserving of the name of Bloody Henry??? I find the debate between FabNayNay and Bandit Queen a common one. I think we all forget the backgrounds and characters of the people involved. I am not justifying anything these royals did, but I think we forget the time and conditions surrounding them. Great article.

Hello Heather, you are quite right. We forget that these things happen 500 years ago, although you could be hung drawn and quartered for treason even in the 1800s, which included political protest or riots or marching in protest. Two political rebels were executed, in Ireland in 1817 just for leading a march like the Chartists in County Clare and would have been hung drawn and quartered but the English feared a riot. Instead both were hung and their bodies beheaded. The point is, we forget that these terrible penalties were not invented by Mary, they existed all over, plus far worse was done in King Henry Viii time and Queen Elizabeth, for religious and political reasons, to rebels and in the wars in Ireland. The terror that monarchs inflicted went on for centuries, because it was the norm. Such beliefs as we may accept and tolerate were seen as dangerous, immoral, treason, a threat to the throne, the world, community, the status quo, went against what the King or Queen said was true. The aim was unity and uniformity. The policy was popular. I don’t condone the actions of the Tudors or Stuarts or any other rulers who passed laws which allowed men and women to die in this way, but we cannot understand why after 500 years. It is just a thing to be thankful that we have grown up, which is why use of the term Bloody Mary has no place among modern history or thinking today.

Cranmer recanted not just out of fear, but due to extreme psychological pressure and carefully organized humiliation. Did you hear about “Moscow trials” – show trials staged in the Soviet Union during the rule of Stalin and directed against the former leaders of opposition? The same tactics and methods intended to break victim. The same desire to strengthen regime by humiliating and killing it’s opponents. The same confidence in ideological “purity” on part of the government. The only difference is that Stalinists shot their victims in prisons while queen Mary and her church had to arrange public executions. In case of Cranmer they got what they deserved – public slap in the face. I greatly respect and admire Cranmer (my attitude has nothing to do with religion becase I am an atheist) and sympathize with his sufferings. Who said he was a weak man and coward? He, being and old man and in poor health, practically alone and isolated from friends and supporters, defended his dignity and resisted authorities for more than two years. For a moment the strength left him and he seemed to be broken, but he could overcome this awful crisis and eventually triumphed over his enemies! As for Mary, I feel nothing but contempt to her. She did not deserve victory and it’s a consolation to think that she and her coreligionists lost battle.

“Poor girl! It’s no wonder she became so embittered & vindictive! Cramner didn’t stand a chance once power was in Marys hands! And who can blame her for taking full advantage of that power, and making one of the main people she considered responsible for her mothers downfall, and eventuall death, pay the ultimate price?”

I can blame her. If it depended on me, I would at first send her to prison to endure three trials ending with death sentence, deprive her of any support, then force her to watch her old friends being slowly killed before her eyes, then sent her to main cathedral church to be publicly abused there for several hours (let she had her coronation again and then with violence and insults and sayings “you are no lady now” forced to change her robes for poor woman’s dress, her head being shaved, her fingers being scraped and all of that in front of many people, let this ceremony be conducted by her most implacable enemy together with her former good friend). I would make her wait for her death month after month, year after year. All this time I would play with her: today I give hope that her life will change for the better, tomorrow I worsen her conditions and so on and so forth. I would send to her my agents who would arrange endless disputes with her about her beliefs until the moment she could not endure it any longer. Let these agents find her weak points and play on them with the aim to break her will. If she wished to make a compromise, I (and my agents on my behalf) would press her to extreme points of humiliation. Of course I would not be satisfied with moderate diplomatic statements, I’d force her to write her declarations of submission several times. Until I would get my victory – I’d extract from the woman I hate so much the admission that she is the most wicked, cruel, abominable creature in the world and I am right in persecuting her. And then I would kill her. All these actions I would do because once, many years ago my father divorced my mother. I am justified, I am just poor little girl.

Claire, thank you for highlighting Thomas Cranmer’s plight for us today. I am in disagreement with one point made, however. I do not believe that Cranmer’s recantations were a desperate attempt to save himself. Instead, I am of the strong opinion that Cranmer fell victim to Stockholm Syndrome, and there is compelling evidence to support that being the driving force of his decision making, especially from the point of the Latimer and Ridley martyrdoms forward.

Hi Beth,

This is a rather old article, from 2011, so before you published your work on Cranmer and Stockholm Syndrome and I think your theory is valid and does make sense.

Oh heavens, I am losing it. I didn’t even see the date of the article…. In the words of Miss Emily Litella, “Nevermind”… lolol.

Don’t worry!

Hi Beth. Do you have a link to your paper or a website that I can read it on? I am sorry, I was trying to recsll who had done the research on this years post, but reading your response reminded me. I did read the article but I don’t recall all the details. I would love to read again if this is possible. Your work is very important and thought provoking. Thanks in advance.

Lyn-Marie BQ.

Here you go… It is the example article for the November 2014 issue of TUDOR LIFE. https://www.tudorsociety.com/magazine/

Many thanks. Looks very interesting.

Cheers BQ

I am Catholic myself but the cruel end of Cranmer makes me feel sick and I pray for the repose of his soul. In answer to the ding dong going on between BanditQueen and FabNayNay, I can see it both ways. It is very hard to support Mary when you consider that in my area, a blind teenager called Joan Waste was burned for getting people to read the English bible to her. Yes, that is true and not a legend. But it is also true that thirty odd years later the drawing, hanging and quartering of the Padley martyrs in the same city of Derby doesn’t reflect well on Elizabeth. Those were wretched times.

Hello Jane, you have hit the nail on the head, thankfully we have grown up and at the time people watching these terrible penalties did not just jeer as with many public executions, but are recorded as having sympathy for the victims, shows human beings have always been capable of compassion and cruelty. The beautiful monuments and memorials to the martyrs from both sides, sometimes in the same spot prove that we have woken up to our terrible errors and moved on to acceptance. We debate such things because quite frankly they make us uncomfortable and so they should. Cranmer himself made the authorities feel uncomfortable, he was the man who had led the country into the very belief system that Mary and her Parliament would rather have been avoided and which, via a complex system of law, education, propaganda and penal code, wished to reverse. Men and women of strong moral fiber and faith, More, Cranmer, Pole, Fisher, Latimer and Campion, plus Margaret Pole, Margaret Clitherow and Jane Huntington were dangerous to the King and Queen because they stood up for their faith so strongly, influenced many others, did not waiver and the government, afraid of their influence, if they could not turn and convert them, as a political win, they had to be removed, the government, afraid and often insecure used death, the ultimate sanction in order to feel safe. MacCulloch suggests that this is partly the motivation for executing and trying Cranmer again for what Mary would see as the ‘greater crime of heresy’ after his trial for treason. The aloofness of any government condemnation of their own people to death has always chilled me to the bone, yet when writing and researching history there is a struggle between feeling horrified and being professional. The human being at the centre of the story always speaks to the emotional side, the heart and even the soul. The memorial I mentioned above in Chester to both one of the first Marian martyrs who was a local man and to three priests, two killed during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell and one in the aftermath of the so called and invented Popish Plot in the 1670s, all practiced in Cheshire marks the execution and site of a great service of reconciliation in the mid 1800s when the memorial was raised. It also marks our moving to be more sensitive to the beliefs of another, to the diversity of humanity and we can mourn all the martyrs and sholars of both the past and present. The Marian reconciliation with Rome was widely popular, it is unfortunate that her legacy does not include her many positive achievements. As a member of the Prayer Book Society as well as many Ecumenical groups I can appreciate his work and influence, as well as being in volved in the past, although I am not able to now, with Catholic prayer and study groups, I can still get the benefit from my own faith, without feeling anything negative about the reformed church. Taize and Erasmus Prayer and the Rosary are all heard by the same Lord, so why can’t His/Her people not live in love and peace and why can’t we accept that some people may not have had a healthy or good experience with the Church and listen to and feel their pain as well?

P.S The story of blind Joan Waste always inspired me. Her story is beautifully told in Tudor Heroine by Beth J Coombes Harris. She was the only reformation martyred in Derby but her story of how she loved to have the Bible read to her is wonderful. How sad and terrible to suffer so at the age of just 22. (1534 to 1556) The Marian government laid the groundwork for a Catholic translation of the Bible, yet it was a crime for any other version. O.K Joan also denied the Real Presence but it was still a very cruel thing to kill people who disagreed with the King or Queen religions policy. I can understand that some people were dangerous, but how could someone who was blind and an ordinary person be a threat? Both Elizabeth I and Mary may have made efforts via propaganda and evangelization and educational tracts, but they were so caught up with the negative ideas that their council spouted that they never really considered that their policies may have made things worse. So many people were killed without any reason at all. Yes there was so much more to these queens, but maybe a bit less fanaticism was needed on both sides.

I see many that are of the opinion that to recant his previous recantations was courageous, and I must disagree. When having tried to save his own skin by lying about his beliefs failed there was nothing to lose when he found that he was still to be burnt. To be courageous a person would have to have some consequence for their courage that wouldn’t be the same consequence had they taken other action. It isn’t courageous for example to jump when there is a net, but not jump when there is no net. The man was going to die either way and the only consequence left to him was in the afterlife, in this way I perceive this to be more cowardice on his part, right down to burning his hand, as he firmly held the belief that he was going to have to answer for his previous recantations (where had he lived he could beg forgiveness in prayer and perform acts of contrition) to a higher authority. Just like Mary thought that burning at the stake may encourage recantations so that a soul was saved Cranmer likely felt similarly with his different faith, and being out of time to save his soul, aired his true beliefs and tried to mete out his own punishment so that he wouldn’t face purgatory or hell.

Thomas Cranmer’s recantations had nothing at all to do trying to save himself. Instead, they were an attempt to please his abusers within an environment where the only points of view within the gross and highly isolated deprivation he endured were those of his abusers. There is nothing related to courage or lack thereof going on here. Instead, his actions were the result of pervasive psychological torment.

Cranmer might be the one situation where Mary really sought revenge, even if it was meant for political gain. Generally, she wasn’t actually inclined to brutality. She was, however, a monarch of her time. Monarchs of this time dealt with dissent harshly, across the board. Mary also ruled for a scant five years, where Elizabeth ruled for nearly forty five years. We cannot know how Mary’s rule would have evolved.

Elizabeth started out with tolerance, but as time went by, and opposition crystallized, she dealt with it in an increasingly harsh manner. The Pope owns some of that. Had he left well enough alone, the Catholics in England would have had an easier time. Of course, the presence on English soil of the Scottish Queen did nothing to help English Catholics. The ensuing plots would have done little to endear Catholics to their Queen.

The truth is, the monarch’s first order of business is retaining the throne. Any threat to that,

whatever its basis, is going to be dealt with by any means deemed necessary. In this time, religious differences fall into this category.

England did not have massacres of Protestants in the way the French did, after all, nor did they have the Inquisition, as did Spain.

We have been fortunate to grow up in a time of far less vicious treatment of dissenters, at least in Europe and America. There is still plenty of room for improvement, and those who use religion as a stepping stone to power risk returning us to a bygone time that should remain bygone.

As for Cranmer, he was a victim of his own success. As he was the architect of the New Religion, Mary needed a public recantation, with the punishment piled on, to prove it was sincere. She didn’t get it. Bully for him.

I’ve actually always felt Mary was the saddest, most abused of the Tudors. Elizabeth, for all her losses, lived a long life, doing what she wanted most-ruling England. But Mary, stuck in the middle of that horrible war between her parents, humiliated time and again, and then disappointed again when she became Queen! What a life!