On this day in history, 18th June 1546, a young woman in her twenties from Lincolnshire was found guilty of heresy and sentenced to burning at the stake.

On this day in history, 18th June 1546, a young woman in her twenties from Lincolnshire was found guilty of heresy and sentenced to burning at the stake.

Antonia Fraser writes of how she had already been cross-examined for heresy the year before and “had responded to her accusers with vigour”1 and survived to fight another day but her days were numbered. Both Stephen Gardiner and Thomas Wriothesley were on a mission to rid the land of heretics, particularly those connected to the court and Anne Askew had connections. Anne’s brother was a member of the King’s household, her sister was married to the steward of the late Duke of Suffolk and it was suspected that she was receiving money from influential court ladies who were connected to Queen Catherine Parr and men like Edward Seymour, the Earl of Hertford, who were suspected of holding “Reformed” views.

Wriothesley saw Anne as a way to bring down these women and so Anne was interrogated and eventually racked by Wriothesley and Richard Rich, who operated the rack themselves when the Lieutenant of the Tower, Sir Anthony Kingston, refused to continue racking the woman after the first turn because such torture was illegal for a woman of her standing. While Kingston dashed off to report the goings-on to the King, Wriothesley and Rich continued racking Anne to try and get her to give them names, and possibly to implicate the Queen. Even though they racked “till her bones and joints were almost plucked asunder”, Anne would only admit to receiving money from the servants of Anne Seymour, Lady Hertford, and Jane, Lady Denny and would not implicate their husbands or the Queen.

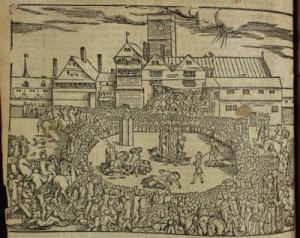

On the 16th July 1546, Anne Askew was burned at the stake at Smithfield with three other Protestants. She had been injured so badly on the rack that she had to be carried to the stake and her body had to be supported on the stake by a seat.

“As the fa*gots were piled high about them, Wriothesly made his way through the throng to offer the four a pardon if they recanted. Anne spoke for them all, crying aloud that she “came not hither to deny my Lord and Master!” The torch was lit and the four died quickly thanks to gunpowder a friend had thrown into the flames. A fortuitous thunderstorm, breaking out suddenly, added to the legend that grew to surround the death of the Fair Gospeler: the thunder, the 18th century ecclesiastical historian John Strype tells us “seemed to the people to be the voice of God, or the voice of an angel”.”2

This courageous young woman lost her life in the flames that day, dying for her faith.

You can read about Anne Askew’s life in my article from last year “Anne Askew Sentenced to Death”.

Notes and Sources

- The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Antonia Fraser, p472-473

- Divorced, Beheaded, Survived : A Feminist Reinterpretation of the Wives of Henry VIII, Karen Lindsey

Poor Anne Askew – she died for being too intelligent and too argumentative for the times. What a tragedy.

That was a horrible scene in “The Tudors.” But I kept wondering why anyone would say anything against the way the church was set up by Henry. Dying for an idea which can not be proven is not going to change anyone’s opinions..

Idea that can not be proven? Have you read your bible lately?

She was another poor victim of changing times, having the view that man, woman or child should be allowed to question religion, not to deny the principles, but to improve and extend the knowledge to the ordinary person,eg, that the bible be in the english language. But in doing this it threatened the power had over the ordinary person that people like Gardiner,Wriothsley, and any other of their elk had, some times I wonder if they did not have some kind of repressed prevertion in administering these tortures on fellow human beings. Especially when it involved women ‘over stepping’ there place. The sad thing is there are still too many people in this modern world with the same fanatical ideals. Although death by fire is an horrendous thought by any stretch of the imagination, but after the excruciating pain and humiliation she had just endured, I would think that any end would be a merciful release, no matter how it came, and thanks to be given to the friend that threw the gunpower to bring that about more swifty. What a courageous, loyal women she was. R.I.P. Anne knowning that your story lives on.

She was actually another mosigyny victim but we have to ask ourselves if this has changed at all.

Oh definately, it is just done in a more subtle, acceptable way now since they outlawed the rack, ducking stools and burning us at the stake!!! ha ha 🙂

Tina, What I meant was that if someone wants to believe that the wafter and wine become the blood and body of Christ, that is their belief and you will not change it by executing people. If you want to believe that it is only a symbolic representation, then that is what you believe. Neither view can be proven. That is a matter of faith. I have no desire to be converted to another person’s beliefs because of their interpretation of the Bible. Yes, I have read most of it. Yes, I have my own opinions about it. No, this is not the place for an a debate over religious interpretations of the Bible.

Definitely did not pay to be an outspoken woman in those days! So much change so fast–these things take time but Henry wanted it to happen immediately. I always wondered about Anne Askew’s life–the details….and I cringe to think about them wracking her–ugh.

Anne,Thats a fact,back in the day it did not pay to be outspoken for anyone man or women.It should have been kept to ones self,they new what the out come was,I cringe to think of any of the torture tools they had back in the day,barely alive then just to be slowly burnd at the stake.I shutter to think, the pain these poor souls endured,but as they say ,loose lips sinks ships.My prayers are with all. Baroness

Violetta and Dawn,

Sorry, not sure what ‘mosigyny’ is, but I think I kinow what you mean. If that is the case, you might want to ask what the sex of the other poor victims were on that dreadful day who assumably were executed for the same ‘crime’. No matter what else we all think about the dreadful sights of that day, there was most certainly equality of the sexes on that scaffold!

Anne Askew knew what she was letting herself in for and was given ample opportunity to recant. The fact that she refused is an extraordinary act of belief and bravery, but surely Anne Boleyn never had such a chance and, in today’s parlance, was ‘stitched up’. I have more sympathy for the latter Anne, whilst admiring the former.

(I hope your comments were tongue in chhek – if not, please don’t t turn this wonderful website into a bra burning excercise.)

I think Violetta meant misogyny and, like you, Chris, I don’t think Henry was a misogynist. As you point out, Anne Askew was executed alongside John Lascelles and two other Protestants and she was more the victim of Wriothesley and Gardiner’s plot to bring down the Queen and influential reformists at court than a victim of her gender and misogyny.

Chris

I can’t speak for Violetta, but in my first comment I certainly did not think I that I was showing more sympathy towards Anne because she was a woman, as I said ‘she was another poor victim of changing times’, not that her torture and execution is a greater wrong because she is female, though correct me if I am wrong, I thought that there was a law in Henry’s time stating that women were not to be tortured, and that is why it deemed to be more shocking by the people of those times. My second point about these men who did this having an extra point to make because she was a woman who dared to voice her opinion in times when it wasn’t the norm, I personally think there could have been an element of that, while trying to bring about the fall of Queen Catherine, and were showing that women were no longer safe from the rack if they dared stand in the way of court matters.

And no I definately don’t want to change this site into a ‘Bra burning exercise’, I wouldn’t want to change anything about this site, its marvelous as it is…..anyway they didn’t have bras in them days!!!! (joke)

My second comment under Violetta’s remark was definately tongue-in- cheek, said in jest and to be taken with a pinch of salt 🙂

P.s just to add that yes Anne could have retracted, but oviously her beliefs were too strong and deep, as were Thomas Moore, John Fisher and all the others that died because of their convictions. She certainly saved Queen Catherine from a certain trip to the block. Even if she had of recanted they still would have executed her along with the rest she would have implicated in doing so.

Misogyny means women hater, or the oppression of women in a male dominated world to obtain the idyll, depending on which dictionary you use.

I wasn’t suggesting Henry was a woman hater, I dont think he was. But I do think that the second meaning can be applied to those times, it was the way of the world then, and long after, which is what makes history so interesting, seeing how things have changed (or not in some cases).

OOOps bras on fire again, best go and put it out!!!! only joking ladies honestly 🙂 🙂 🙂

MY WIFE WE BELIEVE IS A DESCENDANT FROM THE ANNE ASKEW LINE.WE MOVED TO AUSTRALIA SOME 40 YEARS AGO.AROUND THE YEAR 2004 I CONTACTED ANOTHER ASKEW FAMILY TO GET AID FOR THE FAMILY TREE AND TO MY SURPRISE THE ANIMOSITY FROM THE MAN WHEN I MENTIONED ANNE BECAUSE SHE DARED TO SPEAK OUT ABOUT THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH SYSTEM OF HER DAY LEFT ME BEWHILDERED .IT SEEMS THAT AFTER ALL THIS TIME HER STAND AND BRAVERY FOR HER FAITH STILL RANKLE SOME RELIGOUS BIGOTS.

BILL BROOK

It was thought that Anne had 2 children however there is no evidence that they did infact exist nor that if they did they survived infancy. Alot of people have made a link between Anne askew and Margaret Fell claiming she was Annes great granddaughter of which there is no evidence. so I am afraid your wife is unlikely to be decended from her. it is a shame as Margaret is my great Grandmother x10 and it would have been nice to think Anne was also my forbear

I believe I am a descendant of Anne Askew

My paternal grandmother was (nee) Anne Askew who married William Steven Lewis and they lived in Kieraville NSW and later Cronulla NSW

They came out from England in there early 1880s