On 21st June 1529 King Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon appeared in front of Cardinals Wolsey and Campeggio at the Legatine Court at Blackfriars. In 1528, Cardinal Wolsey had been made the Pope’s vice-regent in order “to take cognisance of all matters concerning the King’s divorce” and Campeggio had been made papal legate and sent to England to help Wolsey with the case.

On 21st June 1529 King Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon appeared in front of Cardinals Wolsey and Campeggio at the Legatine Court at Blackfriars. In 1528, Cardinal Wolsey had been made the Pope’s vice-regent in order “to take cognisance of all matters concerning the King’s divorce” and Campeggio had been made papal legate and sent to England to help Wolsey with the case.

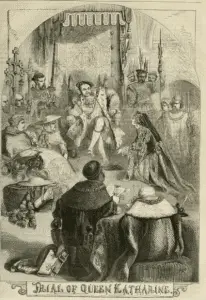

George Cavendish, Wolsey’s gentleman-usher, described how the King sat under a cloth of estate and Catherine “sat some distance beneath the king”.1 Also present were Stephen Gardiner as “scribe”; the Archbishop of Canterbury (William Warham), Richard Sampson and Thomas Abel as counsellors for the King, and John Fisher (Bishop of Rochester) and Cuthbert Tunstall (Bishop of St Asaph) as counsellors for the Queen. The papal commission was read out to the court and the crier officially summoned the King to court, crying “King Henry of England, come into the court.” The King rose and responded “Here, my lords.” The crier then called, “Catherine, Queen of England, come into the court.” Rather than simply confirming her attendance, Catherine got up, approached the King and knelt at his feet. In “broken English”, she then made what David Starkey calls “the speech of her life”:2

“Sir, I beseech you for all the loves that hath been between us, and for the love of God, let me have justice and right, take of me some pity and compassion, for I am a poor woman, and a stranger born out of your dominion. I have here no assured friend, and much less indifferent counsel. I flee to you as to the head of justice within this realm.

Alas! Sir, wherein have I offended you, or what occasion of displeasure? Have I designed against your will and pleasure; intending (as I perceive) to put me from you? I take God ansd all the world to witness, that I have been to you a true, humble and obedient wife, ever comfortable to your will and pleasure, that never said or did any thing to the contrary thereof, being always well pleased and contented with all things wherein you had any delight or dalliance, whether it were in little or much. I never grudged in word or countenance, or showed a visage or spark of discontentation. I loved all those whom ye loved, only for your sake, whether I had cause or no, and whether they were my friends or my enemies. This twenty years I have been your true wife or more, and by me ye have had divers children, although it hath pleased God to call them out of this world, which hath been no default in me.

And when ye had me at first, I take God to my judge, I was a true maid, without touch of man. And whether it be true or no, I put it to your conscience. If there be any just cause by the law that ye can allege against me either of dishonesty or any other impediment to banish and put me from you, I am well content to depart to my great shame and dishonour. And if there be none, then here, I most lowly beseech you, let me remain in my former estate and receive justice at your hands. The King your father was in the time of his reign of such estimation thorough the world for his excellent wisdom, that he was accounted and called of all men the second Solomon; and my father Ferdinand, King of Spain, who was esteemed to be one of the wittiest princes that reigned in Spain, many years before, were both wise and excellent kings in wisdom and princely behaviour. It is not therefore to be doubted, but that they elected and gathered as wise counsellors about them as to their high discretions was thought meet. Also, as me seemeth, there was in those days as wise, as well learned men, and men of as good judgment as be at this present in both realms, who thought then the marriage between you and me good and lawful. Therefore it is a wonder to hear what new inventions are now invented against me, that never intended but honesty. And cause me to stand to the order and judgment of this new court, wherein ye may do me much wrong, if ye intend any cruelty; for ye may condemn me for lack of sufficient answer, having no indifferent counsel, but such as be assigned me, with whose wisdom and learning I am not acquainted. Ye must consider that they cannot be indifferent counsellors for my part which be your subjects, and taken out of your own council before, wherein they be made privy, and dare not, for your displeasure, disobey your will and intent, being once made privy thereto.

Therefore, I most humbly require you, in the way of charity and for the love of God – who is the just judge – to spare me the extremity of this new court, until I may be advertised what way and order my friends in Spain will advise me to take. And if ye will not extend to me so much indifferent favour, your pleasure then be fulfilled, and to God I commit my cause!”3

With that said, Catherine rose to her feet, curtseyed to the King and walked out of the court, ignoring those who tried to make her return to her seat and saying, “On, on, it makes no matter, for it is no impartial court for me, therefore I will not tarry. Go on.”

After a few minutes of stunned silence, Henry VIII had his say, simply repeating what he had said at Bridewell Palace in 1528 about his concerns over the marriage:

“For as much as the queen is gone, I will, in her absence, declare unto you all my lords here presently assembled, she hath been to me as true, as obedient, and as conformable a wife as I could in my fantasy wish or desire. She hath all the virtuous qualities that ought to be in a woman of her dignity, or in any other of baser estate. Surely she is also a noble woman born, if nothing were in her, but only her conditions will well declare the same.”4

Cardinal Wolsey then asked the King to confirm that Wolsey was not “the chief inventor or first mover of this matter” and the King replied, “Nay, my lord Cardinal, I can well excuse you herein. Ye have been rather against me.” The King explained that his doubts about his marriage had been sparked off during negotiations over a potential marriage between his daughter mary and the Duke of Orleans. The French ambassador had apparently wanted assurance that Mary was legitimate, considering that the Queen had formerly been married to Henry’s brother. This query had then made the King begin to doubt the validity of his marriage and ponder whether it was better for the country for him to take another wife.

After hearing from both side, the court was then adjourned for the day.

Also on this day in history

- 1494 – Birth of George Cavendish, Cardinal Wolsey’s gentleman usher and the writer of “The Life of Cardinal Wolsey”.

- 1553 – Letters patent issued changing Edward VI’s heir from his half-sister, Mary, to Lady Jane Grey.

Notes and Sources

- Cavendish, George (1827) The Life of Cardinal Wolsey, 2nd Edition, p211

- Starkey, David (2003) Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII, p241

- Cavendish, p214-217

- Ibid., p218

Picture taken from John Cassell’s Illustrated History of England, Volume II (1856), p193.