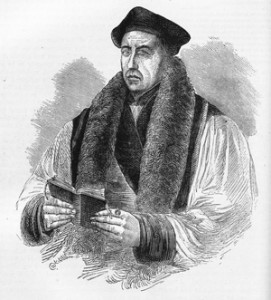

On Wednesday 3rd May 1536, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, who had travelled back to Lambeth Palace from Knole (his country residence) after being summoned back to court, wrote a letter to King Henry VIII:

On Wednesday 3rd May 1536, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, who had travelled back to Lambeth Palace from Knole (his country residence) after being summoned back to court, wrote a letter to King Henry VIII:

“Have come to Lambeth, according to Mr. Secretary’s letters, to know your Grace’s pleasure. Dare not, contrary to the said letters, presume to come to your presence, but of my bounden duty I beg you “somewhat to suppress the deep sorrows of your Grace’s heart,” and take adversity patiently. Cannot deny that you have great causes of heaviness, and that your honor is highly touched. God never sent you a like trial; but if He find you no less patient and thankful than when all things succeeded to your wish, I suppose you never did thing more acceptable to Him. You will give Him occasion to increase His benefits, as He did to Job.

“If the reports of the Queen be true, they are only to her dishonor, not yours. I am clean amazed, for I had never better opinion of woman; but I think your Highness would not have gone so far if she had not been culpable. I was most bound to her of all creatures living, and therefore beg that I may, with your Grace’s favor, wish and pray that she may declare herself innocent. Yet if she be found guilty, I repute him not a faithful subject who would not wish her punished without mercy. “And as I loved her not a little for the love which I judged her to bear towards God and His Gospel, so if she be proved culpable there is not one that loveth God and His Gospel that ever will favor her, but must hate her above all other; and the more they favor the Gospel the more they will hate her, for then there was never creature in our time that so much slandered the Gospel; and God hath sent her this punishment for that she feignedly hath professed his Gospel in her mouth and not in heart and deed.” And though she have so offended, yet God has shown His goodness towards your Grace and never offended you. “But your Grace, I am sure, knowledgeth that you have offended Him.” I trust, therefore, you will bear no less zeal to the Gospel than you did before, as your favor to the Gospel was not led by affection to her. Lambeth, 3 May.”

Before the letter was sent, Cranmer received more information and so added a postscript:

“Since writing, my lords Chancellor, Oxford, Sussex, and my Lord Chamberlain of your Grace’s house, sent for me to come to the Star Chamber, and there declared to me such things as you wished to make me privy to. For this I am much bounden to your Grace. They will report our conference. I am sorry such faults can be proved against the Queen as they report.”1

It is clear from the letter that he has heard about the charges against Anne and that he is shocked. He knew Anne Boleyn well, she was his friend and patron. He writes of how he “was most bound to her” and that he “had never better opinion of woman”. He just can’t believe what has been said about her, but his letter is carefully worded – he cannot be seen to be questioning the King’s actions or offending him in any way. The King was God’s anointed sovereign and his master. In her book Thomas Cranmer: In a Nutshell, Beth von Staats writes of the letter: “Though some view the letter’s prose to be a condemnation of his close friend Queen Anne Boleyn, it is actually an example of highly cautious advocacy. Though he could plant a seed of doubt, Cranmer was wise enough to know not to question the king’s decision-making.”2 And I agree with her. The fact that Cranmer didn’t rewrite the letter on receiving further news shows that he wanted the King to read his words in support of Anne.

Also on 3rd May 1536, Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower of London, wrote his first report to Thomas Cromwell regarding Anne Boleyn’s imprisonment in the Tower of London – click here to find out more – and Sir Edward Baynton, Anne Boleyn’s vice-chamberlain, wrote to Sir William Fitzwilliam, treasurer of the household, informing him that “noman will confesse any thynge agaynst her, but allonly Marke of any actuell thynge”, i.e. only Mark Smeaton had confessed and they were not having any luck getting Sir Henry Norris and George Boleyn, Lord Rochford, to confess to anything. He also wrote of how he was friends with “mastres Margery”, who is thought to be Margery Lyster (née Horsman), one of Anne Boleyn’s ladies-in-waiting, and of her “great fryndeship” with the Queen.3 Perhaps he was trying to get information from her. Margery was obviously in a position to know whether the Queen had been unfaithful, and Eric Ives points out that Margery was never arrested but, instead, moved into the service of Queen Jane Seymour following Anne’s execution.4 If Margery had known about the Queen’s infidelity then she would have been guilty of misprision of treason, and there’s no way that Henry VIII would have let her go unpunished

Notes and Sources

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 10 – January-June 1536, 792.

- von Staats, Beth (2015) Thomas Cranmer: In a Nutshell, MadeGlobal Publishing.

- Cavendish, George (1825) The Life of Cardinal Wolsey, Volume 2, Samuel Weller Singer, p.226.

- Ives, Eric (1992) “The Fall of Anne Boleyn Reconsidered”, p. 6, in English Historical Review.