Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, had died in October 1537 leaving the King grief-stricken and unable to think of remarrying for some time. Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief adviser, was keen to build links with the Schmalkaldic League and when Henry saw that Francis I of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, were becoming friendly, he too looked towards Germany for support. In January 1539, Henry VIII sent Christopher Mont, a member of Thomas Cromwell’s household, as ambassador to Germany to discuss a possible marriage between the Princess Mary, his eldest daughter, and William, Anne of Cleves’ brother, and to “diligently enquire of the beauty and qualities of the eldest of the two daughters of the duke of Cleves, her shape, stature, and complexion, and, if he hear she is such “as might be likened unto his Majesty,””.1 Mont reported back that “Everyone praises the lady’s beauty, both of face and body. One said she excelled the Duchess [of Milan] as the golden sun did the silver moon”, although he was going on hearsay as he had not seen Anne himself.2

In March 1539, Henry sent ambassadors to Cleves to get further reports on Anne and to get a portrait of Anne but the ambassadors encountered difficulties as Anne and her sister kept their faces covered. In the summer of 1539, Henry sent his court painter, Hans Holbein, to Cleves to paint Anne and her younger sister. When the leading English ambassador, Nicholas Wotton, saw Holbein’s portraits of the sisters, he declared that the artist “hath expressyd theyr imaiges verye lyvelye”3 and that others also considered the portraits a good likeness of the young women. Although we do not know what Henry thought of Anne from her portrait, we have to conclude that he liked what he saw as he continued with negotiations.

On the 4th September 1539 William, Duke of Cleves, signed the marriage treaty promising his sister, Anne of Cleves, in marriage to King Henry VIII.4 The Duke then sent the treaty to England, where it was ratified and concluded by early October. Anne arrived in England on 27th December 1539, landing at Deal on the Kent coast. Anne was met by Sir Thomas Cheyne and taken to Deal Castle to rest after her long journey. There, she was visited by the Duke of Suffolk and his wife, Catherine Willoughby, the Bishop of Chichester and various knights and ladies. She was informed that she would be meeting the King, her future husband, at Greenwich Palace at a formal reception in a few days time, but she was to be taken by surprise.

On New Year’s Day 1540, while Anne was resting at Rochester before travelling on to London, an excited Henry VIII turned up. Henry, the impatient and hopeless romantic, just couldn’t wait for his bride to arrive in London and was desperate to see the woman from the portrait, so he decided to follow the chivalric tradition of meeting his future bride in disguise. Tradition said that the love between them would be so strong that Anne would see through his disguise and recognise her future husband, however, as Elizabeth Norton points out, Henry should have learned from the disastrous meeting between his great-uncle, Henry VI, and his bride, Margaret of Anjou.5

Henry VIII arrived at Rochester on 1st January 1540 and sent his attendant, Sir Anthony Browne, ahead of him to tell Anne that he had been sent by the King with a New Year’s gift for her. Browne told Anne and then Henry, in disguise as a lowly servant, entered the room. Anne was not paying much attention to this servant, as she was watching bull-baiting out of the window, so Henry pulled her towards him in an embrace and tried to kiss her. Anne was obviously shocked at such behaviour from a servant, so obviously did not respond to his advances and Henry’s dreams of her seeing through his disguise and falling into his arms lay shattered. The meeting was a complete disaster and the King was humiliated. It was not a good start and Henry decided he did not want to marry this woman. Unfortunately, there was nothing that could be done without offending Anne’s brother, the Duke of Cleves, so the marriage went ahead.

Henry VIII arrived at Rochester on 1st January 1540 and sent his attendant, Sir Anthony Browne, ahead of him to tell Anne that he had been sent by the King with a New Year’s gift for her. Browne told Anne and then Henry, in disguise as a lowly servant, entered the room. Anne was not paying much attention to this servant, as she was watching bull-baiting out of the window, so Henry pulled her towards him in an embrace and tried to kiss her. Anne was obviously shocked at such behaviour from a servant, so obviously did not respond to his advances and Henry’s dreams of her seeing through his disguise and falling into his arms lay shattered. The meeting was a complete disaster and the King was humiliated. It was not a good start and Henry decided he did not want to marry this woman. Unfortunately, there was nothing that could be done without offending Anne’s brother, the Duke of Cleves, so the marriage went ahead.

The chronicler Edward Hall describes Anne on her wedding day:

“Then the Lordes went to fetche the Ladye Anne, whiche was apparelled in a gowne of ryche cloth of gold set full of large flowers of great & Orient Pearle, made after the Dutche fassion rownde, her here hangyng downe, whych was fayre, yelowe and long: On her head a Coronall of gold replenished with great stone, and set about full of braunches of Rosemary, about her necke and middle, luelles of great valew & estirnacion.”

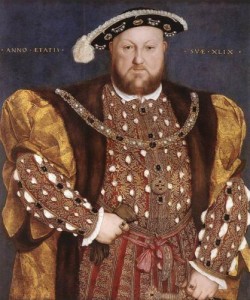

The King wore “a gowne of ryche Tyssue [cloth of gold] lyned with Crymosyn”.6

Hall records that Anne curtsied to the King three times and then the couple were married by Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Anne’s wedding ring was engraved with the words “GOD SEND ME WEL TO KEPE”.

After the ceremony, the bride, groom and guests enjoyed the usual wine and spices, followed by “Bankettes, Maskes, and dyuerse dvsportes, tyll the tyme came that it pleased the Kyng and her to take their rest”. It was time for the all-important consummation of the marriage, something which seems to have been a complete disaster. The next morning, when Thomas Cromwell asked a rather bad-tempered Henry what he thought of his queen, Henry replied:

“Surely, as ye know, I liked her before not well, but now I like her much worse. For I have felt her belly and her breast, and thereby, as I can judge, she should be no maid… [The] which struck me so to the heart when I felt them that I had neither will nor courage to proceed any further in other matters… I have left her as good a maid as I found her.”7

Henry discussed the matter with his physicians, telling them that “he found her body in such sort disordered and indisposed to excite and provoke any lust in him”. Henry was unable to consummate the marriage and blamed it on Anne’s appearances, for he “thought himself able to do the act with other, but not with her”.

On the 6th July 1540, a messenger was sent to Anne to inform her of her husband’s concerns over their marriage and to obain her consent for a church court to investigate. Anne, who must have been terrified after what happened to Anne Boleyn, gave her consent. On the 7th July 1540 a convocation of clergy agreed that “the king and Anne of Cleves were no wise bound by the marriage solemnised between them, and it was decreed to send letters testimonial of this to the king.”8 The invalidity of the marriage was proven by three pieces of evidence: 1) The betrothal between Anne and Francis of Lorraine, 2) Henry’s lack of consent to the marriage and 3) Lack of consummation – Henry declared that “I never for love to the woman consented to marry; nor yet if she brought maidenhead with her, took any from her by true carnal copulation”.9 When Anne was informed of this she wrote to the King confirming that she accepted the annulment. Anne was rewarded handsomely for her acceptance of the situation, receiving jewels, plate, hangings, furniture, money, houses at Richmond, “Blechinglegh” (Bletchingley) and Lewes, and also Hever Castle, the former Boleyn family home. On 28th July 1540, just weeks after the annulment, Henry VIII married his fifth wife, Catherine Howard.

You can read more about the end of Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves in my article Henry VIII divorces Anne of Cleves.

Notes and Sources

- LP xiv. Part 1. 103

- Ibid., 552

- LP xiv. Part 2. 33

- LP xiv. Part 2. 286

- Anne of Cleves: Henry VIII’s Discarded Bride, Elizabeth Norton

- Hall’s Chronicle, Edward Hall, p836

- Burnet, Vol II, p. lxxxvi, quoted in “Thomas Cromwell: The Rise and Fall of Henry VIII’s Most Notorious Minister”, Robert Hutchinson, Chapter 10.

- LP xv. 860

- Burnet

How predictable that she received Hever.It just makes me sigh with disgust.I guess in Henry’s mind that’s where all the lousy women go or come from.

Perhaps so, but I think it was more of a case of sweetening the annulment for Anne, rewarding her for submitting, and it just happened to be a property that Henry had got his hands on. It appears that she really liked Hever so at least it was appreciated by her.

It just seems too odd of a choice for it to be completely accidental.He must have had quite a few castles.It just doesn’t make too much sense to me unless he was trying to make a point.Ugh….

He did give her a number of properties and Hever had only just come into his hands. I think it was just a reward and Henry kept on good terms with Anne of Cleves.

I have a question about the wedding: do we know if the king’s children were there?

I dont beleieve they were even though al 3 had spent Christmas with Henry with Mary acting as Henry’s hostess in lieu of a queen..

Following the aborted visit to Anne, all 3 were sent back to their respective households and didn’t attend the wedding nor the other celebrations surrounding it.

I don’t think the children were present. Henry did not present her to them straight away. It was not like a modern wedding, young children would have been considered too young and Mary had not met her as yet. She married Henry more or less at once. It would not have allowed time for them to attend. Even though it was arranged in advance, it was not normal protocol. Well, not every monarch got married several times, so the protocol had probably never been written.

Reading between the lines, the King was sick and possibly ailing from the leg ulcer. There was turmoil around between the frenemies from Fance And Spain and..Henry has never married without love. All this and a very confused girl as Anne should have been spelled short marriage. She was smart. She kept her status and kept the protection of the king. Sadly the next wife was not that smart.

I would love to know Anne of Cleve’s true opinion of Henry VIII’s physical appearance on their wedding night! She wasn’t the ugly one – he was!

You said it!!!

In body AND mind!

Excellent account of Henry’s meeting with the “Flanders Mare” as he called her. Henry claimed Anne had body odor, but did he smell like a bed of roses? In her Autobiography of Henry VIII, Margaret George writes a brilliant scene about the wedding night. In my very first historical, The Jewels of Warwick, I enjoyed writing about their disastrous encounter.

Henry never called Anne the Flanders Mare. As I have said before this was invented in the 17th century by another author who claimed Henry said it but has no historical backing from any contemporary source. Henry may have complained about her having evil smells about her as he put it but that could refer to anything, not necessarily body smells and I doubt she found his ulcers lovely smelling. Henry was reacting to a bad situation, he did not send her swooning with delight at his romantic gestures; his first impression was not a good one and he could not see past that. It is not clear what is the truth of the dislike between them and much is based on Henry’s outbursts, not solid evidence.

If they looked anything like their portraits I have to say Anne was a rather beautiful lady even compared to standards of 21th century.and I’m not sure about this but I think Henry’s leg was infected back then so the one who had a bad smell was him not Anne.

Cromwell obviously had an agenda here, the reports of Anne being more lovely than the beautiful and young Christina, duchess of Milan are for me being made on his orders. He had the most to gain by convincing Henry of the need to marry a daughter of Cleves; and it was in his interest to get the ambassadors to push for Anne or Amelia, claiming that they are lovely. Their married sister Sylvia was a beautiful woman; their mother was lovely, so by claiming that Anne was also a beauty; the ambassadors who did not actually see her properly could at least hope it was so based on this repute. The portrait by Holbein also shows a lady that is good looking and I do not believe she was ugly. She may not have been the beauty that Henry hoped for and had heard about; she may have been pretty but plain; and Henry built up his hopes too much; so he was bitterly disappointed when he met her, but that is his own fault, not hers.

Henry obviously wanted out of the marriage as soon as he saw Anne on New Years Day but there was not enough time to cancel the marriage, nor any grounds, the contract was water tight; German efficiency at its best. It is clear that from the outset, Henry set this wedding up to fail; he took an instant dislike to the poor woman; he saw in her what he wanted to and he had funny ideas about what sort of lady she was. Henry was going to come up with any excuse he could to get out of the marriage and to dissolve it once he was married. He could not consumate the marriage and he blamed the bride; inventing nonsense about her body and ideas of maidenhood. Now I dare say that in his world view virgins had firm boobs and nice bellies, neither of which poor Anne seems to have, although we only have his word for that; but it was only an excuse for failure on the wedding night. I doubt that Anne knew what to expect either and she seems to have been not just a virgin but totally ignorant of what to do on her wedding night. There is something else to think about: what did Anne think of Henry? He was well over weight; his legs had sores and they smelled. She could not have been that excited about his body either.

The couple had very little time to get to know each other; this was the arranged marriage from hell; they had only seen each other on a couple of formal ceremonial occasions and the fatal New Years Day visit; and could not have spoken to each other very much at all, and now they had to find some sort of chemistry to enable them to do their duty. It is not a great surprise that it was anything but. However, the couple tried once or twice more, but each time it was a failure, embarrassingly so for the King and Henry just wanted out of an unhappy situation. Despite being treated well by the King and his children, being greeted and welcomed everywhere she went, good reports of her graciousness being aclaimed, Anne must have also been happy to end the marriage.

Anne, however, would see herself as the true wife and although she agreed to annul the marriage to please Henry as her Lord and King, she gave Henry her wedding ring to destroy as a ‘thing of no value’. She was a sensible woman and after sending for the original contract of her betrothal to the Duke of Lorraine and her marriage contract with the King of England. She had it examined to attempt to get out of ending the marriage; but having not found anything against it, she agreed. She saw the advantages in accepting this as the will of King Henry. On receiving the news from the Duke of Suffolk and others, and the generous offer that went with it, Anne decided to accept a situation she could not control and to live her life in relative peace and comfort. Anne appears to have been blessed with common sense, but also she had also been married merely for six months; she had nothing to lose by accepting. Katherine had been married for over 20 years and had her daughter to fight for. She had also been crowned and she was devoted to Henry and Mary. She chose what she saw as their righteous inheritance. Anne saw a future without the King that she could make the best of and she accepted the inevitable. There seems to have been something of an agreement also that she was happy to end the marriage as she knew it was not making either of them happy; she could not be content and so agreed.

Hever Castle was not given to Anne because Henry thought she was a terrible women or that all worthless women came from here, but because Hever was taken back as crown property after the Boleyn fall and as one of the most beautiful homes in the country and one of the best castles that Henry was fond of; he considered it as a suitable settlement gift for Anne. It was part of a wider handsome settlement that he gave her; Richmond Palace, Bechley Palace being two he gave her; and several houses, one famous one in Sussex and of course an annual income and servants. Anne was also given the honourable title of the Kings Sister and visited the court as such several times, most notably on New Year 1541 when she spent the eveniing with Henry and his new wife, Katherine Howard, and the two queens danced together. Gifts were exchanged and the three supped together. Hever was obviously a special place for the King and he gave it to Anne as a gift of honour not because he saw her as a worthless queen, but as a sensible and honourable one.

BanditQueen

I’m going to have to disagree with you on the point that Henry considered Anne a worthy queen because if that was the case he would have continued in his marriage to her.Anne received properties as a consolation for her demoted status and to placate her brother in Cleeves who was assured by Henry that no other woman would be higher in status than Anne except the queen.I think Henry was just throwing unwanted property at her to satisfy her brother.I don’t think he especially had any particular fondness for her but it seems more about compensation than anything else to me.

I don’t think the children were present. Henry did not present her to them straight away. It was not like a modern wedding, young children would have been considered too young and Mary had not met her as yet. She married Henry more or less at once. It would not have allowed time for them to attend. Even though it was arranged in advance, it was not normal protocol. Well, not every monarch got married several times, so the protocol had probably never been written.

Please ignore this reply, my device appears to have done something very odd. Happy New Year and Epiphany.

Henry would not have agreed to marry her in the first place if he didn’t consider her worthy. He saw the potential of a match with Cleves and he was Keen enough until the disaster of their first meeting.

We can’t read too much into his subsequent remarks as he would have done anything to escape the marriage he had changed his mind about. His courtesy to her belies his moaning and his treatment later on showed he honoured her as her status decreed. He wasn’t forced into the match. That’s actually a myth. Henry blamed Cromwell, then rewarded him. That makes little sense. He attempted to consummate the marriage and introduced her to his children. Of course he thought her worthy to be his Queen. That he disliked her and changed his mind doesn’t change the fact that she was a good match to begin with.

I have no doubt that Anne took one look at Henry and thanked God and all the saints when he wanted the annulment.

Love that…lol. In the Six Wives series with Keith Mitchell there is a funny scene with Henry and Anne arguing about what they really think of each other in which she tells him that she thinks he is no picture of beauty himself and is clearly put off by him. There is a brief pause before they both burst out laughing and then after some merriment and wine they bash out an agreement to come to terms. Yes, a bit of a fantastic story, but you are right, much as she probably found Henry respectful towards her, she must have been put off by some of his physical aspects. I have read that in private she did complain about his leg, which through no fault of his, must have smelt. I can well imagine that although Anne saw herself as his true wife, would have been disappointed that her marriage failed so quickly, privately at least, she could only have been relieved to be offered an annulment and generous terms. Anne saw Henry as her gracious Lord and wisely agreed. She was given Richmond, Hever, Westhorpe, two other palaces and several smaller houses, including the one which is a museum now at Lewes in Sussex. She was given an honorary title, income and enjoyed her life at Hever and elsewhere. She entertained the King, his daughters, wrote often to Edward, members of his court and council, was a friend to Elizabeth and Mary and the Suffolks, spent New Year with Henry and Katherine Howard and later attended the coronation of Mary I, sharing a carriage with Princess Elizabeth, a great honour. Mary paid for her state funeral in Westminster Abbey. Anne and Henry may well have been put off by each other, but after the marriage ended they got on very well indeed. Anne was a worthy woman and would have been a good and able Queen, but she was probably better off without him.

I am sure Henry was put off by Anne’s failure to welcome his embrace. I am also sure he had no idea how to manage the situation, never having married a woman he did not know fairly well. Easiest thing to do was to annul it.

The son would not have been would only be a year old. nothing ever written about the two women being there

His comments after the first night are written by Henry, also he went on to write that Anne was a very good card player and took his money off him.

He gave her a title that she was pleased with, and so was here brother. It is said he often visited her many times and was fond of her like a brother sister.

On his death bed it is said he called out for Ann , which one?

Where do you get your information from? Complete nonsense as usual.

Edward was actually a few months past three but of course he wasn’t there and neither were Mary or Elizabeth as we know how and when they met her.

Nobody said anything about Henry and Anne playing cards on their first night. That is the film. Again, as said to you already, she couldn’t play cards as it wasn’t proper for a high born German Princess. Anne only took up cards long after being in England when she also learnt music and dancing.

There are a few rumours about his last words but he probably didn’t ask for Anne and it was more likely to be Anne Boleyn.

Yes, she did have the title Our Dearest Sister, but no other title. He gave her three palaces, including Richmond and six houses, including Hever which belonged to her for many years.

She lived a very comfortable life, was often at Court, received Henry and the two Princesses as visitors regularly, never remarried, never had any children and was buried with full honours, next to the high alter in Westminster Abbey. This was paid for by Queen Mary I.