Thank you so much to Sandra Vasoli, author of Je Anne Boleyn: Struck with the Dart of Love for sharing some of her thoughts and research on “The Lady in the Tower” letter. Over to Sandi…

Thank you so much to Sandra Vasoli, author of Je Anne Boleyn: Struck with the Dart of Love for sharing some of her thoughts and research on “The Lady in the Tower” letter. Over to Sandi…

Today, 6 May, marks 479 years since the origination of a compelling and mysterious letter, written according to some by Queen Anne Boleyn to her husband Henry VIII. Ostensibly produced while she was imprisoned in the Tower after having been accused of abominable crimes, the letter is poignant, courageous, noble and masterfully composed.

And for the past 475 years, its authenticity has been hotly debated.

I am captivated by its story. As I researched my second book Je Anne Boleyn: Truth Endures, I became preoccupied with the many tales surrounding this letter. I wondered what it might have meant in the due course of history if it had, in fact, been authored by Anne. And I couldn’t help but consider what Henry’s reaction to it might have been, if he were to have read it. So I determined to discover everything I possibly could about it. I hoped that I might be able to find a clue which had perhaps been previously overlooked, or a series of leads which would indicate its veracity. In the process of searching, I discovered much – enough to cast a bright light on the riddle of the letter; and a shocking, previously overlooked original notation which may change the way we view the tragic story of Anne and Henry.

While watching a tennis match, Queen Anne was interrupted by a messenger on 2 May 1536. He delivered a command that she was to meet members of the King’s Privy Council immediately. Confronted by her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, and two others, she was charged with adultery – thereby treason – and subsequently arrested and taken as a prisoner to the Tower, where she was closely guarded. Her warden was Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower. Kingston had been host to Anne during her stay at the Tower prior to her coronation, so he was familiar to her. She may have taken some small comfort in that knowledge, but it was to serve her no purpose. Kingston was required, along with the women who were assigned as Anne’s sentinels both night and day, to observe, listen, and record any and everything the Queen said and did. These reports were to be delivered to Thomas Cromwell, the King’s Chief Minister.

It was chronicled by Bishop Gilbert Burnet, a mid 17th century antiquarian and a collector and preserver of records and documents, in his The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, that once locked in the Tower, Anne made “deep protestations of her innocence, and begged to see the King, but that was not to be expected.”1 This fact had been recorded by Constable Kingston, in one of five letters he wrote to Cromwell documenting Anne’s captivity; Burnet viewed those letters.

Having been refused the chance to see her husband to try and convince him of her innocence (whether or not Henry would have agreed to see Anne is another question), Anne wavered, over the following days, between deep despair and staunch resolution. It was her great desire to communicate with Henry and it follows naturally that, in the absence of a personal meeting, she would demand the privilege of writing to him. While her jailers may have been able to refuse her an audience, still, Anne was the Queen. It would have been an extraordinary act of defiance to forbid her the right to compose a letter to her husband the King. Yet Kingston was responsible for maintaining control of the desperate situation and was under orders to dispatch all information about her behaviors, her conversations, any single utterance to Cromwell, in anticipation that she would surely incriminate herself. He may not have thought it wise to allow Anne to privately correspond with the King without his knowing (and reporting) exactly what had been said. It makes sense, then, that Anne would have been permitted to dictate a letter, which was written for her either by Kingston himself, one of the ladies in attendance, or a scribe.

The letter’s content is as follows:

“To the King from the Lady in the Tower” [Heading said to have been added by Thomas Cromwell]

Sir, your Grace’s displeasure, and my Imprisonment are Things so strange unto me, as what to Write, or what to Excuse, I am altogether ignorant; whereas you sent unto me (willing me to confess a Truth, and so obtain your Favour) by such a one, whom you know to be my ancient and professed Enemy; I no sooner received the Message by him, than I rightly conceived your Meaning; and if, as you say, confessing Truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all Willingness and Duty perform your Command.

But let not your Grace ever imagine that your poor Wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a Fault, where not so much as Thought thereof proceeded. And to speak a truth, never Prince had Wife more Loyal in all Duty, and in all true Affection, than you have found in Anne Boleyn, with which Name and Place could willingly have contented my self, as if God, and your Grace’s Pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forge my self in my Exaltation, or received Queenship, but that I always looked for such an Alteration as now I find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer Foundation than your Grace’s Fancy, the least Alteration, I knew, was fit and sufficient to draw that Fancy to some other subject.

You have chosen me, from a low Estate, to be your Queen and Companion, far beyond my Desert or Desire. If then you found me worthy of such Honour, Good your Grace, let not any light Fancy, or bad Counsel of mine Enemies, withdraw your Princely Favour from me; neither let that Stain, that unworthy Stain of a Disloyal Heart towards your good Grace, ever cast so foul a Blot on your most Dutiful Wife, and the Infant Princess your Daughter.

Try me, good King, but let me have a Lawful Trial, and let not my sworn Enemies sit as my Accusers and Judges; yes, let me receive an open Trial, for my Truth shall fear no open shame; then shall you see, either mine Innocency cleared, your Suspicion and Conscience satisfied, the Ignominy and Slander of the World stopped, or my Guilt openly declared. So that whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your Grace may be freed from an open Censure; and mine Offence being so lawfully proved, your Grace is at liberty, both before God and Man, not only to execute worthy Punishment on me as an unlawful Wife, but to follow your Affection already settled on that party, for whose sake I am now as I am, whose Name I could some good while since have pointed unto: Your Grace being not ignorant of my Suspicion therein.

But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my Death, but an Infamous Slander must bring you the enjoying of your desired Happiness; then I desire of God, that he will pardon your great Sin therein, and likewise mine Enemies, the Instruments thereof; that he will not call you to a strict Account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me, at his General Judgement-Seat, where both you and my self must shortly appear, and in whose Judgement, I doubt not, (whatsover the World may think of me) mine Innocence shall be openly known, and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only Request shall be, That my self may only bear the Burthen of your Grace’s Displeasure, and that it may not touch the Innocent Souls of those poor Gentlemen, who (as I understand) are likewise in strait Imprisonment for my sake. If ever I have found favour in your Sight; if ever the Name of Anne Boleyn hath been pleasing to your Ears, then let me obtain this Request; and I will so leave to trouble your Grace any further, with mine earnest Prayers to the Trinity to have your Grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your Actions.

Your most Loyal and ever Faithful Wife, Anne Bullen.

From my doleful Prison the Tower, this 6th of May.

Upon reading this missive, one is struck by its tenor of familiarity; that which, even in the direst of circumstances, is emblematic of the close relationship between husband and wife. Her opening line… “Sir, Your Grace’s Displeasure and my Imprisonment are things so strange unto me, as what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant” is reminiscent of arguments known to couples throughout the ages. She then chastises him for allowing her to be confronted by her uncle, Norfolk, who by that time was her open enemy (and had a great deal to do with the construction of the plot against her). In the second paragraph she delivers a blow by telling him she is well aware that his “Fancy” has turned to “some other subject.” But she then carefully expresses her humility, telling him she is well aware that he raised her from “a low estate”. She pointedly refers to herself as “Anne Boleyn, with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself…”

Further on, Anne is true to the piquant nature for which she was well known. She tells him that if he has already decided of her that she is guilty of his “Infamous Slander”, and that her death will “bring you the enjoying of your desired happiness”, then she hopes for Henry’s sake that God will pardon him for his “unprincely and cruel usage”, for, as she reminds him – they will both shortly appear before God and be subject to His judgement. She adds the final jolt: she is confident God will know her to be innocent and she will be sufficiently cleared. Her implication is strong: as for Henry? She worries for the salvation of his eternal soul due to his Great Sin.

Anne then agonizes for the men she knows have been unjustly imprisoned on her behalf. In this paragraph one can feel her anguish: she begs Henry to be lenient with them if ever he loved her, just as a woman would do when imploring a man with whom she had been intimate. Finally, she ends by reminding him – not that she is Queen – but that she is simply his loyal and ever faithful wife, Anne Boleyn.

The provenance of the letter is convoluted. Numerous early historians have included references to it in their collections, or treatises about the history of England. These include Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648), John Strype (1643 – 1737), Gilbert Burnet (1643 – 1715), Bishop White Kennett (1660 – 1728), Sir Henry Ellis (1777 – 1869), Agnes Strickland (1796 – 1874), and James Froude (1818 – 1894). Only a few of these state that they actually saw the letter which they considered to be the ‘original’. It is reported by the earliest historians that the letter was “said to be found among the papers of Cromwell then Secretary”.2 Anne’s letter, according to the accounts of several of these historians, was found along with the five letters Kingston had written to Cromwell, in his personal papers some time after his own beheading in 1540 at the hands of Henry.

There are several early versions of the letter extant. What makes this mystery even more difficult to solve is the fact that none of them, though all are written in an early (16th century) script, appear to be in handwriting identifiable as Anne’s. Therefore when one refers to the ‘original’ letter: the one which was found in the deceased Cromwell’s belongings, it is, in fact, a transcription and not a document actually penned by Anne. My research leads me to firmly believe that this letter, which was kept by Thomas Cromwell along with the other records of Anne’s imprisonment, was scribed. That, for some specific reason, it was written by someone other than Anne, while being dictated by Anne herself. This document – the scribed letter, the one which was in Cromwell’s papers – is held carefully at the British Library in the Cotton Manuscripts. It now remains as just a portion of the original, the sides having been scorched and burned away in a fire at the Ashburnam House Library in 1731, where this document, among many others, was being stored. So after 1731, only a part of this particular letter would have been readable.

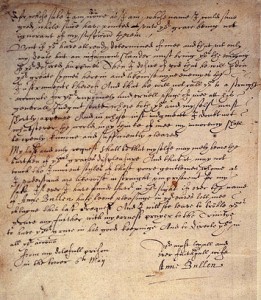

Prior to 1731, then, at least two copies were made of the complete, scribed, original letter. One is headed with the words ‘Queen Anne Bullen to King Henry the 8 found among T. Cromwells papers’ (the one in the photo above). The other copy exists in an ancient volume in the British Library: ‘Collection of Letters of Noble Personages’, which is part of the Stowe manuscripts. This copy was almost certainly written by an enigmatic figure in London in the early 1600s, known only as The Feathery Scribe. This scrivener transcribed hundreds of documents, thousands of words, for such patrons as Sir Robert Cotton, Sir Francis Bacon, John Donne, Henry King, the Earl of Leicester, William Lord Burghley, and John Fisher. The Stowe collection containing this version of the letter was completed prior to 1628,3 making it the earliest known reproduction of the ‘original’.

My forthcoming book Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower will detail all of my findings along with images of the early copies of the letter. There are intriguing questions to consider: who was first to find the letters – Kingston’s and Anne’s – in Cromwell’s private papers after his death? And why was Anne’s with Kingston’s? Why did Cromwell keep it? It seems obvious that it was never delivered to Henry, else why would it have remained in his possession? What would Henry’s reaction to it have been had he read it? Might it have swayed him? We will never know. What evidence can be pieced together today to demonstrate convincingly that Anne authored this composition, and what facts refute claims by some historians that it is a forgery?

The implications of the genuineness of such a heartrending, personal letter, and the fact that it never reached its intended reader, are actually quite dramatic as one considers Anne’s cruel fate. Read the details resulting from exhaustive research in my book early this summer, and learn why I believe without any doubt that Anne’s appeal to Henry is completely authentic.

Coupled with the text of such a heartbreaking letter is a finding which left me completely astounded. In the course of my search I uncovered a contemporary notation within the Stowe collection of manuscripts which refers to Henry’s great grief, on his deathbed, for his fatal decision concerning Anne. The legitimacy of this notation is certain: its significance is stunning. I will provide the complete text, along with an image of the notation, and a discussion of its interpretation in the Nutshell series book.

These recordings, expressed by two people whose entwined lives had such a profound fate, add to the pathos of events which haunt us today, almost five centuries since their occurrence.

Click here to read Sandi’s article about her visit to the Vatican archives to see Henry VIII’s love letters to Anne Boleyn.

Sandra Vasoli earned a bachelor’s degree in English and biology from Villanova University before embarking on a thirty-five-year career in human resources for a large international company.

Sandra Vasoli earned a bachelor’s degree in English and biology from Villanova University before embarking on a thirty-five-year career in human resources for a large international company.

Having written essays, stories, and articles all her life, Vasoli was prompted by her overwhelming fascination with the Tudor dynasty to try her hand at writing fiction. While researching what would eventually become her Je Anne Boleyn series, Vasoli was granted access to the Papal Library. There she was able to read the original love letters from Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn—an event that contributed greatly to the creation of her fictional memoir.

Vasoli currently lives in Gwynedd Valley, Pennsylvania, with her husband and two greyhounds. She is currently working on Je Anne Boleyn: Truth Endures and Anne Boleyn’s Tower Letter: In a Nutshell which will be published by MadeGlobal Publishing.

Notes

- The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, Gilbert Burnet, Vol I Book III, p 198.

- Lord Herbert of Cherbury; The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth; 1649; Thomas Whitaker, London; p 382.

- http://www.celm-ms.org.uk/repositories/british-library-stowe.html

Sources

- British Library Catalogue of English Manuscripts http://www.celm-ms.org.uk/

- British Library Cotton MS Otho CX fol. 232r

- British Library Stowe MS 151

- British Library Lansdowne MS 979

- Burnet, Gilbert; The Historie of the Reformation of the Church of England; Richard Chiswell, London

- Ives, Eric; The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn; Blackwell Publishing; 2004

- Lord Herbert of Cherbury; The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth; 1649; Thomas Whitaker, London

- Ridgway, Claire; The Fall of Anne Boleyn; MadeGlobal Publishing; 2012

- Weir, Alison; The Lady in the Tower; Ballantine Books; 2010