A big welcome to my dear friend Sandra Vasoli, author of Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower: A New Assessment , Struck with the dart of love: Je Anne Boleyn Book 1 and the forthcoming Truth Endures: Je Anne Boleyn Book 2, who has written this guest article for us today. Thank you, Sandi!

A big welcome to my dear friend Sandra Vasoli, author of Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower: A New Assessment , Struck with the dart of love: Je Anne Boleyn Book 1 and the forthcoming Truth Endures: Je Anne Boleyn Book 2, who has written this guest article for us today. Thank you, Sandi!

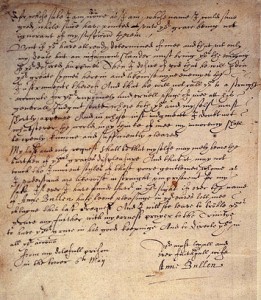

Today, 6 May, marks 480 years since the creation of a compelling and mysterious letter, written according to some by Queen Anne Boleyn to her husband Henry VIII. Ostensibly produced while she was imprisoned in the Tower after having been accused of abominable crimes, the letter is poignant, courageous, noble and masterfully composed.

And for the past 475 years, its authenticity has been hotly debated.

Upon first reading it, I became captivated by it. That fascination has not waned – in fact, it has only increased as I have come to know more about Anne Boleyn – the events of her life and the nuances of her nature. And it is as significant to me today as when I first encountered it.

While researching the second and final book in my Je Anne Boleyn series: Truth Endures, I discovered much misconception and confusion about the letter which may represent Anne’s final recorded words to her husband, Henry VIII. I decided to dig for as many original facts as I might be able to uncover about the source of the document. I also wanted to know what its provenance was: where had it come from and who held it over the course of hundreds of years? Would its source and its pathway shed light on its legitimacy? I wondered what it might have meant in the due course of history if it had, in fact, been authored by Anne. And I couldn’t help but consider what Henry’s reaction to it might have been, if he were to have read it. In the process of searching, I discovered startling facts – dramatic enough to cast a bright light on the riddle of the letter.

I also uncovered a shocking, apparently mostly overlooked original notation which alters our view of the tragic story of Anne and Henry…

On the afternoon of 2 May 1536, Queen Anne Boleyn was one of a group of nobles watching a tennis match at Greenwich. It is unlikely that Anne was completely absorbed in the match; events of the previous several days had been unsettling, and on May Day, her husband had abruptly left a scheduled jousting tourney – clearly disturbed – after having been told something by a messenger. His actions did not bode well, and were layered upon disagreements and tensions she and Henry had shared since the middle of April. A royal courier sought her out and delivered a command that she was to meet members of the King’s Privy Council immediately. Confronted by her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, and two others, she was charged with adultery – thereby treason – and to her great dismay was subsequently arrested and taken prisoner to the Tower. Upon her arrival, she was met by Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower. Kingston had been host to Anne during her stay at the Tower prior to her coronation, so he was familiar to her, and although she may have taken some small comfort in that knowledge, it was to serve her no purpose. Kingston was required, along with the women who were assigned as Anne’s sentinels both night and day, to observe, listen, and record any and everything the Queen said and did. These reports were to be delivered to Thomas Cromwell, the King’s Chief Minister.

On the afternoon of 2 May 1536, Queen Anne Boleyn was one of a group of nobles watching a tennis match at Greenwich. It is unlikely that Anne was completely absorbed in the match; events of the previous several days had been unsettling, and on May Day, her husband had abruptly left a scheduled jousting tourney – clearly disturbed – after having been told something by a messenger. His actions did not bode well, and were layered upon disagreements and tensions she and Henry had shared since the middle of April. A royal courier sought her out and delivered a command that she was to meet members of the King’s Privy Council immediately. Confronted by her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, and two others, she was charged with adultery – thereby treason – and to her great dismay was subsequently arrested and taken prisoner to the Tower. Upon her arrival, she was met by Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower. Kingston had been host to Anne during her stay at the Tower prior to her coronation, so he was familiar to her, and although she may have taken some small comfort in that knowledge, it was to serve her no purpose. Kingston was required, along with the women who were assigned as Anne’s sentinels both night and day, to observe, listen, and record any and everything the Queen said and did. These reports were to be delivered to Thomas Cromwell, the King’s Chief Minister.

A chronicle of her imprisonment was recorded by Bishop Gilbert Burnet, a 17th century antiquarian and collector and preserver of important historical documents. In his work entitled The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, he wrote that once locked in the Tower, Anne made “deep protestations of her innocence, and begged to see the King, but that was not to be expected.”1 This fact had been recorded by Constable Kingston, in one of five letters he wrote to Cromwell documenting Anne’s captivity; Burnet viewed those letters.

Having been refused the chance to see her husband to try and convince him of her innocence, Anne wavered, over the following days, between deep despair and staunch resolve. It was her great desire to communicate with Henry, and it follows naturally that, in the absence of a personal meeting, she would demand the privilege of writing to him. While her jailers may have been able to refuse her an audience, Anne was still Queen. It would have been an extraordinary act of defiance to forbid her the right to compose a letter to her husband, the King. Yet Kingston was responsible for maintaining control of the desperate situation and was under orders to dispatch all information about her behaviors, her conversations, or any utterance to Cromwell, in anticipation that she would surely incriminate herself. It was almost certainly Thomas Cromwell’s decision to disallow Anne a private correspondence with the King. Anne’s personal entreaty to her husband would present much too great a risk for Cromwell; it was critical that he maintain careful oversight of her imprisonment: too much depended on her certain indictment. So the logical conclusion was to permit Anne to compose a letter to Henry – but only through dictation; her words to be recorded by a scribe of Cromwell’s choosing – someone in whom he could place his implicit trust.

The letter’s content is as follows:

“To the King from the Lady in the Tower” [Heading said to have been added by Thomas Cromwell]

Sir, your Grace’s displeasure, and my Imprisonment are Things so strange unto me, as what to Write, or what to Excuse, I am altogether ignorant; whereas you sent unto me (willing me to confess a Truth, and so obtain your Favour) by such a one, whom you know to be my ancient and professed Enemy; I no sooner received the Message by him, than I rightly conceived your Meaning; and if, as you say, confessing Truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all Willingness and Duty perform your Command.

But let not your Grace ever imagine that your poor Wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a Fault, where not so much as Thought thereof proceeded. And to speak a truth, never Prince had Wife more Loyal in all Duty, and in all true Affection, than you have found in Anne Boleyn, with which Name and Place could willingly have contented my self, as if God, and your Grace’s Pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forge my self in my Exaltation, or received Queenship, but that I always looked for such an Alteration as now I find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer Foundation than your Grace’s Fancy, the least Alteration, I knew, was fit and sufficient to draw that Fancy to some other subject.

You have chosen me, from a low Estate, to be your Queen and Companion, far beyond my Desert or Desire. If then you found me worthy of such Honour, Good your Grace, let not any light Fancy, or bad Counsel of mine Enemies, withdraw your Princely Favour from me; neither let that Stain, that unworthy Stain of a Disloyal Heart towards your good Grace, ever cast so foul a Blot on your most Dutiful Wife, and the Infant Princess your Daughter.

Try me, good King, but let me have a Lawful Trial, and let not my sworn Enemies sit as my Accusers and Judges; yes, let me receive an open Trial, for my Truth shall fear no open shame; then shall you see, either mine Innocency cleared, your Suspicion and Conscience satisfied, the Ignominy and Slander of the World stopped, or my Guilt openly declared. So that whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your Grace may be freed from an open Censure; and mine Offence being so lawfully proved, your Grace is at liberty, both before God and Man, not only to execute worthy Punishment on me as an unlawful Wife, but to follow your Affection already settled on that party, for whose sake I am now as I am, whose Name I could some good while since have pointed unto: Your Grace being not ignorant of my Suspicion therein.

But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my Death, but an Infamous Slander must bring you the enjoying of your desired Happiness; then I desire of God, that he will pardon your great Sin therein, and likewise mine Enemies, the Instruments thereof; that he will not call you to a strict Account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me, at his General Judgement-Seat, where both you and my self must shortly appear, and in whose Judgement, I doubt not, (whatsover the World may think of me) mine Innocence shall be openly known, and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only Request shall be, That my self may only bear the Burthen of your Grace’s Displeasure, and that it may not touch the Innocent Souls of those poor Gentlemen, who (as I understand) are likewise in strait Imprisonment for my sake. If ever I have found favour in your Sight; if ever the Name of Anne Boleyn hath been pleasing to your Ears, then let me obtain this Request; and I will so leave to trouble your Grace any further, with mine earnest Prayers to the Trinity to have your Grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your Actions.

Your most Loyal and ever Faithful Wife, Anne Bullen.

From my doleful Prison the Tower, this 6th of May.

Upon reading this missive, one is struck by its tenor of familiarity; that which, even in the direst of circumstances, is emblematic of the close relationship between husband and wife. Her opening line: “Sir, Your Grace’s Displeasure and my Imprisonment are things so strange unto me, as what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant” is reminiscent of arguments known to couples throughout the ages. She then chastises him for allowing her to be confronted by her uncle, Norfolk, who by that time was her open enemy (and had a great deal to do with the construction of the plot against her). In the second paragraph, she delivers a blow by telling him she is well aware that his “Fancy” has turned to “some other subject.” But she then carefully expresses her humility, telling him she is well aware that he raised her from “a low estate”. She pointedly refers to herself as “Anne Boleyn, with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself…”

Further on, Anne is true to the piquant nature for which she was well known. She tells him that if he has already decided of her that she is guilty of his “Infamous Slander”, and that her death will “bring you the enjoying of your desired happiness”, then she hopes for Henry’s sake that God will pardon him for his “unprincely and cruel usage”, for, as she reminds him – they will both shortly appear before God and be subject to His judgement. She adds the final jolt: she is confident God will know her to be innocent and she will be sufficiently cleared. Her implication is strong: as for Henry? She worries for the salvation of his eternal soul due to his Great Sin.

Anne then agonizes for the men she knows have been unjustly imprisoned on her behalf. In this paragraph one can feel her anguish: she begs Henry to be lenient with them if ever he loved her, just as a woman would do when imploring a man with whom she had been intimate. Finally, she ends by reminding him – not that she is Queen – but that she is simply his loyal and ever faithful wife, Anne Boleyn.

The provenance of the letter is convoluted, yet it is, in fact, traceable from its resting place today back to the fateful day of 6 May 1536. Numerous early historians have included references to it in their collections or treatises about the history of England. These include Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648), John Strype (1643 – 1737), Gilbert Burnet (1643 – 1715), Bishop White Kennett (1660 – 1728), Sir Henry Ellis (1777 – 1869), Agnes Strickland (1796 – 1874), and James Froude (1818 – 1894). Only a few of these state that they actually saw the letter which they considered to be the ‘original’. It is recorded by the earliest of those historians that the letter was “said to be found among the papers of Cromwell then Secretary”.2 Anne’s letter, according to the accounts of several of these historians, was found along with the five original letters Kingston had written to Cromwell, amongst his personal papers some time after his beheading in 1540 at the hands of his master, the King.

There are several early versions of the letter extant. What makes this mystery even more difficult to solve is the fact that none of them, though all are written in an early (16th century) script, appear to be in handwriting identifiable as Anne’s. Therefore, when one refers to the ‘original’ letter, the one which was found in the deceased Cromwell’s belongings, it is, in fact, a transcription and not a document actually penned by Anne. My research leads me to firmly conclude that this letter, which was secretly kept by Thomas Cromwell along with the other records of Anne’s imprisonment, was scribed. I have every belief that the letter was dictated by Anne herself. This document – the scribed letter, the one which was in Cromwell’s papers – is today held carefully at the British Library in the Cotton Manuscripts. It now remains as just a portion of the original, its sides having been scorched and burned away in a fire at the Ashburnam House Library in 1731, where this document among many others, was being stored at that time. So after 1731, only a part of this particular letter would have been readable.

Prior to 1731, then, at least two copies were made of the complete, scribed, original letter. One is headed with the words ‘Queen Anne Bullen to King Henry the 8 found among T. Cromwells papers’ (the one in the photo above). The other copy exists in an ancient volume in the British Library: Collection of Letters of Noble Personages, which is part of the Stowe manuscripts. This particular copy was almost certainly made by an enigmatic figure known only as The Feathery Scribe. In London during the early 1600s, this scrivener transcribed hundreds of documents, thousands of words, for such patrons as Sir Robert Cotton, Sir Francis Bacon, John Donne, Henry King, the Earl of Leicester, William Lord Burghley, and John Fisher. The Stowe collection, containing this version of the letter, was compiled prior to 1628, making it the earliest known reproduction of the ‘original’.3

My book, Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower – A New Assessment, details my findings along with very rarely published images of the early copies of the letter. There are intriguing questions which I consider and discuss: who was first to find the letters – Kingston’s and Anne’s – in Cromwell’s private papers after his death? And why was Anne’s with Kingston’s? Why did Cromwell keep it? It seems almost a certainty that it was never delivered to Henry.

My book, Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower – A New Assessment, details my findings along with very rarely published images of the early copies of the letter. There are intriguing questions which I consider and discuss: who was first to find the letters – Kingston’s and Anne’s – in Cromwell’s private papers after his death? And why was Anne’s with Kingston’s? Why did Cromwell keep it? It seems almost a certainty that it was never delivered to Henry.

What would Henry’s reaction to it have been had he read it? Might it have swayed him? Sadly, we will never know. What evidence can be pieced together today to demonstrate convincingly that Anne authored this composition, and what facts refute claims by some historians that it is a forgery?

The implications of the genuineness of such a heartrending, intimate letter, and the fact that it never reached its intended reader, are quite moving as one considers Anne’s cruel fate. Read the details resulting from exhaustive research in my book, which is available on Amazon, and learn why I believe without any doubt that Anne’s appeal to Henry is completely authentic.

Coupled with the text of such a heartbreaking letter is a finding which left me completely astounded. In the course of my search, I uncovered a contemporary notation within the Stowe collection of manuscripts which refers to Henry’s great grief, on his deathbed, for his fatal decision concerning Anne. The legitimacy of this notation is certain: its significance is stunning. I provide the complete text, along with a very clear image of the notation, and a discussion of its interpretation in the book.

These recordings, expressed by two passionate people whose entwined lives had such a profound fate, add to the pathos of events which haunt us today – almost five centuries since their occurrence.

Read more about this letter in Sandra’s book Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower: A New Assessment – click here to view it on your country’s Amazon site. Its ISBN is 978-8494372155.

Sandi’s two Je Anne Boleyn novels are available to pre-order on kindle now and come out on 19th May 2016. Click on the links below for more information:

Sandi’s two Je Anne Boleyn novels are available to pre-order on kindle now and come out on 19th May 2016. Click on the links below for more information:

- Struck with the Dart of Love: Je Anne Boleyn Book 1 (revised edition) – http://getbook.at/dartoflove

- Truth Endures: Je Anne Boleyn Book 2 – http://getbook.at/truthendures

Sandra Vasoli earned a bachelor’s degree in English and biology from Villanova University before embarking on a thirty-five-year career in human resources for a large international company.

Having written essays, stories, and articles all her life, Vasoli was prompted by her overwhelming fascination with the Tudor dynasty to try her hand at writing fiction. While researching what would eventually become her Je Anne Boleyn series, Vasoli was granted access to the Papal Library. There she was able to read the original love letters from Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn—an event that contributed greatly to the creation of her fictional memoir.

Notes and Sources

- The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, Gilbert Burnet, Vol I Book III, p 198.

- Lord Herbert of Cherbury; The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth; 1649; Thomas Whitaker, London; p 382.

- http://www.celm-ms.org.uk/repositories/british-library-stowe.html

it makes you wonder the extent of Cromwells hatred of Anne that Henry never received this letter( as far as we know–if it is an orginal). the only saving grace is that Cromwell paid the price for over-reaching Henry, but sadly, another Ann suffered—but knowing Henry he may have done ,but wanted Jane instead. Oh the mysteries of history that we cannot solve

Interesting article, and I hope to read your book Sandra. I wondered if you had come across Retha Warnicke’s article on Anne Boleyn’s forged letters? She discusses the 6 May letter and concludes that it is a forgery; some of her arguments are quite persuasive.

http://humanities.byu.edu/rmmra/pdfs/11.pdf

Great article. How do we know that the letter didn’t reach Henry? If Henry wanted to get rid of Anne, the letter simply failed to change his mind … similar to the effect of Cromwell’s letter Also, the idea of Cromwell keeping the letter makes more sense if Henry had seen it; if Cromwell wanted to make sure Henry didn’t see it, wouldn’t he destroy it?

I think Esther makes a very good point. It would make sense that if Henry never saw the letter, Cromwell would most likely have destroyed it. I really believe after all that I’ve read about the Tudor histories, that Henry never loved anyone but himself. His obsession with Anne was just that, an obsession and once he had her he started resenting her, considering all the time and trouble his relentless quest to make her his wife and queen had caused him. Similarly, I don’t for one minute believe that Anne ever loved Henry. I know these are just my own opinions. It must have been very hard to hold off his relentless pursuit and I don’t blame her for holding out for a lawful marriage, which of course would include the crown. But there’s no way I’ll ever believe that she loved him. How could any woman love such a disgustingly self-absorbed, merciless and cruel man? Let’s not forget that he also murdered her beloved brother, as well as several of her friends who once were his friends too – all because he had to have his way. I do admit that their union had some very positive results – the creation of the Church of England and of course the reign of Elizabeth I, which resulted in England becoming the mistress of the seas.

I also agree that the letter is authentic. Even if it was actually written by a scribe, it was certainly dictated by Anne. I doubt she would have been permitted to write her own letter. I think Joyce brings up some good points: Was Henry’s obsession with Anne only an obsession? And, how much did Anne really love Henry? My students have been asking these questions for a long time, as have I.

Absolutely fantastic and well-written article! 🙂

Thank you Renita!!! It’s an endlessly fascinating topic, with many views. Let me just say this about Henry and Anne’s love: I had the chance to study the original love letters that Henry wrote to Anne, in the Vatican Library, and that experience forever changed my belief about their relationship. I 100% believe that Anne loved Henry greatly, and that her love for him grew and grew over time until they were a happy and comfortable couple in love. This I came to know by his increasing familiarity with how he wrote, the terms of endearment he used, how he joked with her, and how panicked he was when he thought she might die of the sweat. Unfortunately there are no published copies of any of the letters except a couple – the one with the heart – and it’s just hard to describe how much feeling comes through when you see them in person. Addressing Joyce above, who is so mad at Henry for what he did (understandably!) don’t forget that when Anne and Henry began their relationship he was wonderful – handsome, funny, talented, generous, and good hearted. Yes he did leave his first wife… but Anne was in love, and lots of people have relationships with men who have left first wives!

Hello Janice, Conor and Esther – thanks for reading the article, and offering great questions – all which are so valid, and which I have addressed (to the extent possible) in my book. Esther, of course we don’t know 100% that the letter did not reach Henry, and I do discuss this at some length. If Henry had seen it, would it have made a difference? At that moment, I think probably not – but we do know that when Cromwell sent Henry a letter when Cromwell was imprisoned and awaiting death, Henry read the letter several times and it was said that he wavered. So…??? I think that the letter of Anne’s would not have ended up hidden in Cromwell’s private belongings had it been delivered to Henry. Just doesn’t seem logical. As a lawyer, Cromwell would have felt uncomfortable destorying the letter. Instead, he hid it. Janice – I think Cromwell had too much to lose if Anne was released from jail. Did he hate her? Maybe not – but at that point it was clearly her or him. And he wasn’t going to take that risk. Conor – thank you for including the link to this book and article by Retha Warnicke. I have read her book The Rise and Fall of AB but had not seen the article. I can’t discuss it at length in this comment, but I take great difference with Ms Warnicke’s theories about Anne… and even though she is an educator, I suggest that her theories are pure supposition – based upon her somewhat antagonisticviews about Anne (she regularly states as fact that Anne’s final miscarriage was a deformed fetus. We absolutely do not know that to be true. It may merely have been a partially formed child – born well before its time.). Mine are a significant departure from hers – I also do not like that she states unequivocally that the letter is a forgery. She has no way of proving that statement. In short, she has misplaced the writing, stating it to be Elizabethan – it is certainly contemporaneous with the 1530’s (although not Anne’s), and her assumptions about the wording of the letter are based upon her interpretation of the face value of the words. I fully believe that the letter has a much more organic meaning, and that it is very much the product of Anne’s message to her husband. For a little more about how I interpret the letter’s wording, see my article in the ABF as linked above: “AB’s Emotional Last Letter to Her Husband Henry”. Thanks for the discussion!

As a modern-day lawyer, I have grave doubts that the Tudor era version of my profession has the same legal ethics that apply now. Since the rules against destroying evidence come from the same concerns as those against presenting false evidence, the fact that Cromwell’s status as a lawyer didn’t seem to disturb him when securing false evidence means that I doubt that his status as a lawyer would make him uncomfortable destroying the letter. After all, unless Henry was part of the scheme to get rid of Anne (where the letter probably would not change his mind) then Cromwell would be in grave danger if Henry ever found out that he had kept it. ,

Hi Esther, sure KH was …

As Cromwell would not act on his own on such a matter.

In France during the famous “Fouquet’s trial”, we could find just and only one judge refusing to condemn the king’s victim (Louis XIV and especially Colbert had good reasons to have him shut up and ordonned this “even-handed” court to condemn him to death) and I want to name him : Lefèvre d’Ormesson.

And our “Roi-Soleil” could be considered a liberal sovereign when compared with KH …

I guess Anne when sending such a letter was very aware of how hopeles it was.

So if these words are hers – they sound well however -, it is rather for her a way to reaffirm herself, her loyal feelings and her rank.

Neither her, nor her predecessor never disappointed me on crucial points.

I won’t say a word on their husband.

What man on earth would dare dream be sent such a stirring letter from his beloved ?

Yes Retha Warnicke does harp on about the deformed foetus yet there’s no evidence there was one, it was Nicholas Sander who mentioned that some fifty years later to blacken her name, hence the rather deragotory comments he made about her appearance yet he never even met her, Warnicke says that this alleged foetus was proof of Anne’s sexual misdemeanours especially with her brother and of practising witchcraft yet I believe she’s just built her theory around Sanders accusations and made a hundred out of one, Anne was never accused of witchcraft although Henry said he had been seduced into the marriage with Anne by sorcery yet I think it was an off the cuff remark, sories do circulate and people will believe anything if they want to, there’s no contemporary source to back it up and In fact De Carles called it a beautiful child, I don’t think Warnicke is very credible with her theories and regarding Anne’s alleged letter many historians have dismissed it as a forgery including Warnicke yet whose to say their right, I’m not sure about this one I said some time ago I think Cromwell may well have destroyed the letter if it was a fake yet is it possible it fell into another pair of hands and this person or persons preserved it for posterity? Maybe one day the truth will come out and till then it does make for interesting dinner conversation.

Seduced ? It sounds like the famous sentence by Valmont (“it is beyond my control”).

Christine, you are s right, this theory about Anne’s alleged “witchcraft” comes from what some “loyalists” (to KH’s former queen) wanted to believe; by then among people, most were shocked by her rise and coronation.

I did not know about this foetus’ story – however it seems another sordid detail of the same story indeed.

But Anne would also indulge some staunch partisans.

And it might be one of them who kept this letter – why not ?

I made a mistake in my previous posting, I meant I think if the letter was real, eg written by Anne then Cromwell would possibly have chosen to destroy it. Thank you Bruno for agreeing with me, I don’t think Warnicke is a fan of Anne and is therefore biased against her, I don’t think biographers should be biased for or against their subject tho I suspect some of them are, the deformed foetus story is rubbish and it was just another attempt to blacken Anne’s name but mud sticks that’s why five hundred years later these lurid stories about her being a sexually depraved creature resonate down the centuries, Anne sums it up perfectly in a little dirge she wrote from the Tower during her darkest hour when she states quite simply, ‘Ye seek for that shall not be found’!.

Thank you Christine for telling me about the dirge, very interesting point indeed !

As I already admitted, I am definitely biased FOR Anne Boleyn.

Maybe the fact that I admire much her predecessor can now and then help balance my biased mind ?

However, this site and many of its readers make me see how wrong I happen to be sometimes.

About the woman, I just think she was “fit for the job” (as queen consort) and not at all a “parvenu” with the implication of the word.

But coming from foreign courts (french one especially), she was seen as “exotic” meaning a sort of adventuress, both fascinating in her time already and dangerous(it can explain why KH chose to name her a witch or so; not only he tried to alleviate his own responsibility, but in a way that could meet common gossip against his queen; I am not kidding when I say that it is a shame for a husband, but also a real throw-back coming from a “Renaissance Prince” who should have enlightened his contemporaries, instead) …

And so, this “rubbish”, the right word, alas

I don’t know if this letter was forged or not (different arguments …).

But it suits so well with what we know of Anne’s temper.

And so moving – letting us imagining a woman dignified when faced with her own, very unfair death.

Joyce VandenBerg, you are right in seeing in KH no worthy shelter for a loving heart .

In fact, I barely understand how a woman could just fall in love with such a man.

But in Anne’s assertions (if these are hers), we see some gratefulness towards her husband.

I don’t see any dumbness, nor grating irony of her in the words, but rather a desperate call to a man she believed she had known .

I might be naive (my idols being KH’s first two wives, I tend to take for true anything showing how noble and dignified their temper), but this letter is just wonderful in my opinion (and Sandra Vasoli’s comments as well)

thank you Bruno! I agree to you… ‘a desperate call to a man she believed she had known.’ Very well put.

I have never believed that the letter was anything but genuine, the writer clearly knows the King intimately, the manner of writing is personal and feminine, the phrases those of a lover, desperate for the favour and presence of her partner before whom she needs to make her case that she is not having an affair, has not betrayed his trust and has always been faithful, no matter what they have heard to the contrary. The letter is a touching but dignified plea from a wife to a husband. Anne does acknowledge that Henry has raised her up and she owes all to him but then calls herself his dear and loving and humble wife. Anne also believes Henry still to be a fair and just King who would give her a fair hearing, even though he has allowed Norfolk to arrest her, though why she should think him her enemy, rather than simply acting as the chief counsellor and on Henry’s command is rather obscure. Henry did have a good reputation for justice, but this had not been the case in the last couple of years and since the accident it was starting to decline even more. Yet, Anne had faith in her husband and somehow thought that if she could offer her case before him, he would find her innocent. What Anne had not grasped was that the entire thing was a set up and Henry had already turned his eyes and hears away from her, believing the charges to be true. Anne hoped that her influence and love for Henry would have moved him and perhaps this is what Cromwell feared. Cromwell had gone to great pains to keep the accused from the King and to monitor all correspondence. Every word of the Queens were reported back to Cromwell and filtered through him to the King. The women in the Tower were his and the King’s spies but Cromwell could not risk Henry seeing this letter, he may actually be moved to see his wife and forgive her. The evidence that he had this letter in his private papers is very revealing, he clearly had hidden this from Henry, preventing any hope of an audience for Anne, as well as accidentally preserving the letter for prosperity.

Another wonderful article on this insightful and precious letter that gives us a rare look at the mind and heart of Anne and an intimate connection with her and how she felt during this her darkest days.