Thank you to author and historian Toni Mount for visiting the Anne Boleyn Files as part of the celebrations for her forthcoming book How to Survive in Medieval England.

Thank you to author and historian Toni Mount for visiting the Anne Boleyn Files as part of the celebrations for her forthcoming book How to Survive in Medieval England.

Over to Toni…

My new book, How to Survive in Medieval England, published by Pen & Sword, is a guide to travelling in history: what to expect, how to dress, how to stay safe and what to look for on the menu – all a visitor needs to know in order to blend in with the locals. Trust me, blending in is a good idea because any odd behaviour, unusual clothing or strange accent could land you in trouble. Medieval folk are wary of in-comers and inclined to accuse them of any crime committed or blame them for causing a horse to become lame or a house to catch fire.

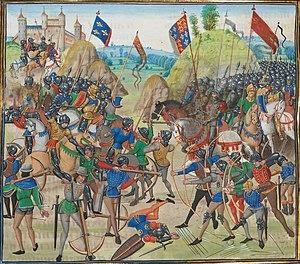

If you were able to go back in time to medieval England, so much would be very different and many things missing – technology, from engines to the Internet. Medical care would be primitive and public transport non-existent. All work would be manual; warfare would mean face-to-face combat and be very bloody. So if you are a young man destined to go into battle, how would you make the best of it? Perhaps it would be wise to study the art of war.

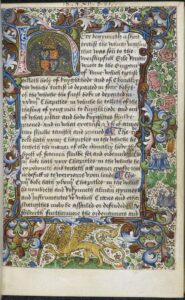

If you’re serious about getting involved, I advise you to read the popular instruction book of the day: Vegetius’ hand book for soldiers, De re militari, [On Military Things]. Surprisingly, Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus had written his book way back in the fourth century AD and no one had bettered it since. Vegetius wasn’t even a soldier but more of a financial manager to the Roman emperor, so perhaps his idea was that the emperor should know how best to spend his money on military matters and not waste it. What he wrote became the most influential military treatise in the Western world, affecting European battle tactics, methods of warfare and military training right through the medieval period and beyond.

[British Library MS Royal 18A xii, f.1]

Since everyone who is anyone (those likely to wage war across Europe, at least) has probably read Vegetius, you’ll be at a disadvantage if you don’t. We know King Richard III had a copy that was probably commissioned for his son, Edward, Prince of Wales. It was reckoned a vital subject for a young nobleman to study and an essential teaching aid.

Luckily, in 1408, Thomas, Lord Berkeley, translated the Latin version of Vegetius’ book into English and at some point the text was updated to include the more modern weaponry becoming available, such as longbows and cannon. De re militari is divided into four sections. The first is about selecting and training your men, the necessity of daily exercise to keep them fit: running and jumping, marching and even swimming. How to handle swords, shields and other hand weapons is included with instructions for leaping on and off a horse with a sword in your hand. There are details on setting up and fortifying a camp depending on whether it’s a hasty affair with the enemy close, or a leisurely construction with time to spend on making it more defensible and comfortable. The second book tells of the structure of Roman legions in Vegetius’ day, which is interesting but not so relevant, but also includes a list of ‘engines of war’, added to by later writers to include new technology, like gunpowder.

Book three is most useful and well used, setting out the general rules of warfare and basic military theory, including strategy, maintaining supply lines, tactics and – most important – how to keep your army healthy and battle-ready. Here are a few vital points from Vegetius:

- He who wants peace should prepare war.

- The best plans are those of which the enemy knows nothing until they happen.

- Every army should be kept busy and so remain sharp; idleness makes them dull.

- Exercise and weapons practice keeps men more healthy than doctors and medicines.

- Good commanders never fight openly in the field unless forced to do so by circumstance or unexpected happenings.

Vegetius must have thought in depth about what an army commander needs to know and he provides invaluable instructions on how to prevent a mutiny, how to manage inexperienced troops, the most effective positions for battle and where to position your captains to maintain communications between you and them and them and their men as they go into action.

The final Book Four deals with the detailed construction of fortifications and, therefore, the best ways to undermine and bring them down. There is also a section on naval warfare, ship-building and how best to foretell and cope with bad weather at sea.

If you don’t have your own army to command, having studied Vegetius, at least you’ll know what your leaders are doing wrong. However, don’t be too free with your superior knowledge and excellent military advice; it could be dangerous. Kings, princes, dukes and lords always think they know best and, of course, God is on their side. Telling them they’re making a big mistake could be your biggest mistake: they won’t appreciate it and the consequences for you could be unpleasant, though whether any worse than defeat, is hard to reckon beforehand. Perhaps you could just leave your copy of Vegetius lying around where they’re certain to see it, book-marked to the relevant pages. If they do lose the battle but you both survive, it’s best not to say, ‘I told you so’.

Vegetius’ book was still the go-to handbook on warfare into the eighteenth century but some of his instructions would have been difficult to comply with at any time during its thousand year plus history. For example, he advises that tall recruits make better soldiers to intimidate the enemy and have longer reach with a weapon so you should choose men at least 5 feet 10 inches tall in Roman measurement [172 cms]. Since the average height of adult males in Roman Italy [168 cms] was at least 2 inches below his ideal – and remained so into the nineteenth century – you may be unable to follow this stipulation. But my best advice is: leave warfare to those who are trained for it from childhood, if you possibly can. It’s a noisy, bloody, dirty business.

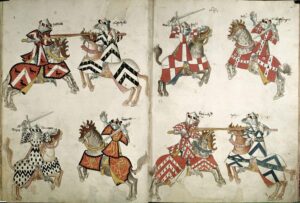

[British Library MS Harley 4205, ff. 19v-20]

Readers can find out far more about medieval lives, meet some of the characters involved and get a ‘taste’ of the food of the time in How to Survive in Medieval England, my new book from Pen & Sword, published on 30th June 2021 and available for pre-order now on Amazon – click here.

Blurb:

Imagine you were transported back in time to Medieval England and had to start a new life there. Without mobile phones, ipads, internet and social media networks, when transport means walking or, if you’re fortunate, horse-back, how will you know where you are or what to do? Where will you live? What is there to eat? What shall you wear? How can you communicate when nobody speaks as you do and what about money? Who can you go to if you fall ill or are mugged in the street? However can you fit into and thrive in this strange environment full of odd people who seem so different from you?

All these questions and many more are answered in this new guide book for time-travellers: How to Survive in Medieval England. A handy self-help guide with tips and suggestions to make your visit to the Middle Ages much more fun, this lively and engaging book will help the reader deal with the new experiences they may encounter and the problems that might occur. Know the laws so you don’t get into trouble or show your ignorance in an embarrassing faux pas. Enjoy interviews with the celebrities of the day, from a business woman and a condemned felon, to a royal cook and King Richard III himself. Have a go at preparing medieval dishes and learn some new words to set the mood for your time-travelling adventure. Have an exciting visit but be sure to keep this book to hand.

Toni Mount is a history teacher and a best-selling author of historical non-fiction and fiction. She’s a member of the Richard III Society’s Research Committee, a regular speaker to groups and societies and belongs to the Crime Writers’ Association. She writes regularly for Tudor Life magazine, has written several online courses for www.MedievalCourses.com and created the Sebastian Foxley series of medieval murder mysteries. Toni has a First class honours degree in history, a Masters Degree in Medieval History, a Diploma in English Literature with Creative Writing, a Diploma in European Humanities and a PGCE. She lives in Kent, England with her husband and has two grown-up sons.

Toni Mount is a history teacher and a best-selling author of historical non-fiction and fiction. She’s a member of the Richard III Society’s Research Committee, a regular speaker to groups and societies and belongs to the Crime Writers’ Association. She writes regularly for Tudor Life magazine, has written several online courses for www.MedievalCourses.com and created the Sebastian Foxley series of medieval murder mysteries. Toni has a First class honours degree in history, a Masters Degree in Medieval History, a Diploma in English Literature with Creative Writing, a Diploma in European Humanities and a PGCE. She lives in Kent, England with her husband and has two grown-up sons.

Web: http://www.tonimount.com

Social:

https://www.facebook.com/toni.mount.10/

https://twitter.com/tonihistorian

https://www.instagram.com/toni.mount.10/

You can catch Toni at the other stops on her blog tour (click to enlarge):