Historians, particularly popular writers, have customarily identified Katherine Howard’s relationships as consensual. Believing that she was, in fact, older than she actually was, they have suggested that she was the dominant party in her liaisons.

Historians, particularly popular writers, have customarily identified Katherine Howard’s relationships as consensual. Believing that she was, in fact, older than she actually was, they have suggested that she was the dominant party in her liaisons.

Tracy Borman termed Katherine ‘a sexual predator’, believing that Katherine ‘knew exactly what she was doing’.1 Lacey Baldwin Smith similarly affirmed in his biography of the queen: ‘that Catherine knew exactly what she was doing is undeniable’.2 These accounts have largely ignored the early modern culture of sexual coercion, while failing to factor in their analyses culturally constructed notions of masculinity and the subservient position of women within aristocratic households. This short article seeks to redress this deficiency by examining Katherine’s experiences in the 1530s in line with these cultural and social conditions.

Because Katherine identified her seducers as ‘vicious’ and persuasive, it is helpful to examine early modern constructions of masculinity and attributes that were deemed essential to successful manhood. Early modern men were socialised to be fiercely protective of their honour. Jennifer Feather and Catherine E. Thomas’s research has demonstrated that, because social expectations for men came under extreme pressure during this period, masculine ideals became closely connected with aggression.3 Violence was a way in which manhood was reaffirmed and protected from threat for, as Alexandra Shepard notes, misgivings emerged in this period that, ‘far from being self-contained exemplars, many men constantly worked against the patriarchal goals of order and control’.

With this understanding of early modern masculinity in mind, it is worth examining sixteenth-century responses to sexual violence and forms of coercion. Garthine Walker noted that pre-modern societies did not acknowledge women to be victims in the same way in which modern society does.5 As today, rape was rarely prosecuted and had a low conviction rate in all early modern jurisdictions while, again as with today, rape was vastly under-reported.6 Partly, this silence ensued because of contemporary notions of shame and dishonour. Women were entreated to guard their chastity and present a modest and chaste demeanour at all times, to safeguard the honour both of themselves and of their families. It is significant, in this context, that the dowager duchess of Norfolk instructed her granddaughter Katherine to remain silent about her sexual past when she arrived at court in 1539, in order to ensure that scandal did not besmirch the Howard name.7

The early modern period, moreover, saw muddy distinctions between ‘persuasion’, ‘seduction’ and ‘rape’, all of which were terms to explain and describe coercion.8 When, in November 1541, Katherine confessed to her sexual relations with Francis Dereham, she testified that Dereham, ‘by many persuasions procured me to his vicious purpose’ and referred to ‘the subtle persuasions of young men and the ignorance and frailty of young women’.9 Historians have failed to consider the importance of language here. Lyndal Roper noted that the language used by men and women to describe sexual experiences was fundamentally gendered. As Warnicke noted in relation to Katherine, ‘not one of her comments indicates she enjoyed the affair with Dereham’, or, for that matter, Manox, since ‘a girl’s loss of maidenhead in a society esteeming virginity could result in emotional as well as painful physical issues’.10 Because she was a member of one of the premier noble families in the kingdom, in which family members were married off in prestigious alliances with other elite families, it does not seem likely that Katherine would heedlessly and unthinkingly have plunged with reckless abandon into sexual relationships with no consideration of her own, or her family’s, honour. From an early age, she would have been educated as to the importance of preserving her honour and modesty, in order to redound to the wellbeing and advantage of her family.

As today, consent in the early modern period was central. Describing instances of rape and sexual coercion necessarily involved a description of sex, which worked to the advantage of accused men, who sought to deflect an accusation of rape by asserting that they had enjoyed sexual intercourse with the consent of the woman concerned.11 This privileging of male testimony has remained continuous across time, for modern historians tend to assume that Katherine was lying when she testified that Dereham had raped her. Female victims were, moreover, disadvantaged by the cultural construction of ‘interior consent’, which assumed that reluctant women actually provoked rape and found pleasure in it.12 This advantaged male aggressors, who could seduce non-consenting women with the justification that their victims had enjoyed or desired their seduction.

Women who remained silent about their experiences were viewed with distrust or suspicion, since ‘a woman’s silence was interpreted as a form of collaboration with her assailant, suggesting her consent after the act if not before’.13 Because Katherine remained silent about her experiences until her downfall in late 1541, she was viewed as having encouraged her seducers’ advances. That she experienced distress and emotional turmoil, however, is clear from her confession, in which she informed Cranmer that ‘the sorrow of my offences was ever before my eyes’.14

Important continuities have remained across time. Then, as now, male testimony tended to be privileged over women’s, while the burden of responsibility for sexual misconduct was laid on women and meant that women who were thought to have encouraged their seducers ‘by word or deed’ were judged to have been culpable.15 That male testimony was privileged in Katherine’s downfall there is no doubt: because the interrogators accepted Culpeper’s admission that he and the queen had discussed their love for one another and had planned to consummate their love, they never asked Katherine about the topic of her discussions with Culpeper in Lincoln and elsewhere, ‘perhaps because they assumed adultery occurred’.16

Although Katherine confessed to illicit communications with Manox and Dereham and to meeting in secret with Culpeper after her marriage, she never stated that she was guilty of adultery. Any analysis of her life, or that of any premodern woman more broadly, must factor in contemporary gender expectations. Attention must be directed to social and cultural constructions of both sexuality and honour. This failure to do so in previous accounts has resulted in the general acceptance that Katherine’s sexual affairs were consensual and voluntary. When attention is given to early modern notions of sexual coercion and honour, however, it is impossible for this interpretation to remain viable. Furthermore, historians should remain sensitive to the use of language and the way in which it was gendered. Katherine’s admission of the ‘persuasions’ of both Manox and Dereham cautions against accepting, at face value, the limited evidence of their interactions. Rather, it appears that she was a victim of early modern notions of sexuality, coercion, and blame in which male aggressors were privileged and female victims viewed with suspicion and distrust.

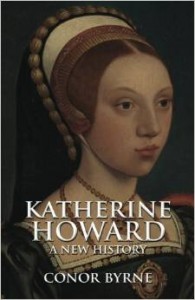

Katherine Howard: A New History by Conor Byrne

Conor is the author of Katherine Howard: A New History, which was published in August 2014.

In this new full-length biography of Katherine Howard, Henry VIII’s fifth wife, Conor Byrne reconsiders Katherine’s brief reign and the circumstances of her life, striping away the complex layers of myths and misconceptions to reveal a credible portrait of this tragic queen.

By reinterpreting her life in the context of cultural customs and expectations surrounding sexuality, fertility and family honour, Byrne exposes the limitations of conceptualising Katherine as either ‘wh*re’ or ‘victim’. His more rounded view of the circumstances in which she found herself and the expectations of her society allows the historical Katherine to emerge.

Katherine has long been condemned by historians for being a promiscuous and frivolous consort who partied away her days and revelled in male attention, but Byrne’s reassessment conveys the mature and thoughtful ways in which Katherine approached her queenship. It was a tragedy that her life was controlled by predators seeking to advance themselves at her expense, whatever the cost.

The book is available from Amazon and your usual book store.

Notes and Sources

- Tracy Borman, Elizabeth’s Women: The Hidden Story of the Virgin Queen (London, 2009), p. 72.

- Lacey Baldwin Smith, A Tudor Tragedy: The Life and Times of Catherine Howard (Stroud, 2009), p. 55.

- Jennifer Feather and Catherine E. Thomas, Violent Masculinities: Male Aggression in Early Modern Texts and Culture (New York, 2013).

- Alexandra Shepard, Meanings of Manhood in Early Modern England (Oxford, 2006), p. 88.

- Garthine Walker, ‘Sexual Violence and Rape in Europe, 1500-1750’, in Sarah Toulalan and Kate Fisher (eds.), The Routledge History of Sex and the Body: 1500 to the Present (Abingdon, 2013), p. 430.

- Ibid.

- Retha M. Warnicke, Wicked Women of Tudor England: Queens, Aristocrats, Commoners (New York, 2012), p. 60.

- Walker, ‘Sexual Violence’, p. 433.

- HMC, Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Marquis of Bath Preserved at Longleat, Wiltshire, vol. 2 (Dublin, 1907), pp. 8-9.

- Warnicke, Wicked Women, p. 60.

- Walker, ‘Sexual Violence’, p. 434.

- Warnicke, Wicked Women, p. 51.

- Walker, ‘Sexual Violence’, p. 434.

- Retha M. Warnicke, ‘Katherine [Catherine; nee Katherine Howard] (1518×24-1542), queen of England and Ireland, fifth consort of Henry VIII’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2008); accessed online at http://oxforddnb.com/view/article/4892?docPos=3.

- Walker, ‘Sexual Violence’, p. 435.

- Warnicke, Wicked Women, p. 76.

I thought she was guilty of adultery but if she was really innocent that is really tragic and I am sure your right about the way men treated women in that era. I guess she had very bad luck to be born in that era and to have a very unforgiving husband

Katherine grew up poor and hardly considered an A-list Howard. The circumstances of her pre-pubescent childhood and lessons learned can only be guessed at. In the loosely supervised household of the old Duchess, nighttime shenanigans took place among the teenage ladies including dalliances with young men, a situation we should be able to relate to today because sexual activity resulting from natural hormonal urges is unchanged from that time. Was this pretty young thing a temptress looking for needed affection or the hapless victim of a smooth talker? My guess is the affairs were were mutually agreed upon and enjoyed.

I’m not completely sure of that either. You are certainly accurate in pointing out she was the “poor relation,” & in those days, promiscuity ran rampant in the lower classes & even possibly in the cases of the minor nobility. Everything I have ever read leads me to believe the Dowager Duchess certainly had her hands full with all those

kids & was preoccupied at best, downright neglectful at worst. Also, the problem lies with her “character.” This I put in quotations because everything written about her was done by her enemies, including her uncle, who never acknowledged her before she caught the eye of the King or the Dowager Duchess for that matter. History books claim she wasn’t the sharpest tool in the shed. Considering the fact that she trusted the same man who lead his other INNOCENT niece to her death ( he had to have known she was innocent- the charges against her would have made Agrippina, wife of Roman Emporer, Claudius & mother to Nero, blush!) without blinking an eye, an execution she WITNESSED, for that matter, makes me wonder if not completely stupid, than surely she was immature & naive. Whether or not the music teacher or Dereham actually forced themselves on her is something we will never know, but ONE rather unseeming trait in some men of low character has existed since the beginning of time & that was the age old trick of lying about being in love to get the girl into bed. In that time, many of the clergy literally blamed ALL women for sin. In all their “enlightenment,” they believed since Eve supposedly got her & Adam tossed out on their ass from the Garden of Eden, naturally ALL women were no good. They blamed any dubious deeds on the females. (Thomas Cramner was different than most, but this was the world they grew up in). We will never know what really happened, but she WAS overly trusting. I think it was a date rape situation, I think he might have been invited to her bed. He probably used the pre-contact speech, very convenient, how he kept THAT away from anyone else’s ears. Then, I believe things got out of hand. I doubt very highly a young, foolish girl, scared for her very soul would have lied to the Archbishop, who from all accounts, I have heard, was a kind man. She would have been afraid of the fires of hell, no doubt, but this is a girl who has been ignored her whole life, until her family saw the value her looks & youth could bring them. She trusted that evil bastard, uncle of hers, she rose to the top at a meteoric speed. She had NO exposure to court or intrigue, & she was out of her element. Cramner would have seen right through her should she have lied. Not only that, but everything had been stripped from her with the exception of a couple maids who you can bet would have stayed as far away from her as humanly possible. She had that bitch, Jane Parker, ANOTHER person she should NEVER have trusted. It was HER evidence that cemented the trumped up charges against the Boleyns. Now, who is left? The kindly, fatherly Archbishop Cranmer, who, as I understand, DID try his best to provide some kind of comfort despite the fact it was HIM who outed Katherine & Culpepper in a note to the King. She was terrified, & I think he felt sorry for her. Her personality was one of a lonely girl desperate to please, she just wanted people to be nice to her. She got stuck marrying an overweight, old, sick man- I mean the writing was on the wall with Culpepper. She told the truth about everything else- admitting to the precontract might have saved her life. I think Cranmer went in there in righteous anger for his friend, the King, but to his surprise, ended up pitying the tragic Queen & maybe he tried to convince her to admit to this, in the hopes maybe that she would have been stuck in a nunnery somewhere. Yet, this girl, went on with the charges with sexual assault, KNOWING full well the implications of her words.

Such bullshit. Katherine was a young woman married to an elderly (in that time period), obese, and unhealthy man. She committed adultery and was caught. The end. Too bad Rolling Stone wasn’t around in the 1500s and could help her lie about rape.

While I am not of the opinion that Katherine was raped, there is no evidence that Katherine did in fact commit adultery. Just because she had an older, obese, unhealthy husband does not mean that she was committing adultery. We don’t know what was going on between her and Culpeper. While I personally don’t believe that he was manipulating her, the evidence can be read that he was and that she was meeting him to keep him quiet. Just because there has been an incident in the news which is now being disputed, it does not mean that Katherine was not abused, manipulated or even raped. I don’t see the relevance of your reference to Rolling Stone and I find your comment offensive too, both to myself and our guest writer.

You are very easily offended. So, according to your guest, now Katherine Howard was an innocent victim, just like Anne Boleyn. All men are b8st8rds and all women are innocent victims. You are hosting a history website, not a Harriet Harman funded rant against men. You should expect such comments. Whist I do not agree with the above use of language, I agree with her sentiment and you should not be so touchy about receiving such feedback. ( I have no idea about the Rolling Stone reference.)

You didn’t read the comment that I deleted and it was visitors to the site who were offended and I acted on that. It is my site and I want people to enjoy using it. I’m not being touchy, I am responding to feedback from those who emailed me and I don’t think it’s appropriate to discuss specific legal cases on here, including sharing the details of those claiming that they were raped. That is not relevant to this article and it was encouraging people to contact that person. I don’t agree that I should expect such comments. It wasn’t relevant and it was not appropriate.

This article, whether you agree with it or not and I don’t agree with some of Conor’s views, was not a rant against men, the writer is a man, it was an examination of the claims Katherine made in interrogations and the various perceptions historians have of her.

If Clair is sensitive to a remark that is made then it is her right too !! This is her page Clair has done her research and in my view has far more knowledge than any of us !!!there is no need to be rude or sarcastic about a comment that u really didn’t understand .Power and money meant an awful lot to some men 500 yrs ago and would do anything for personal gain no such thing as equality ! What happened to Katherine was tragic she was a young girl who wanted some fun an attention from men she messed up badly but I do agree with Clair I think she was abused and used by men after all she was born into a mans-world women should be seen and not heard like some women on this page !!!

Thank you, Claire and Susan. If we had more people like you who understood rape culture and what what creates it (hint: language choices matter), then this would be a better world.

To accept or completely reject the idea that she might be innocent of such accusations is in my opinion archaic. It saddens me to think that we have not learned from our past but continue to repeat it by hastily judging and labeling someone without proof. It is always best to listen to all possibilities and not strictly believe just one side without complete proof.

Lovely article. I think perhaps the truth lies somewhere in between. I do believe Katherine was seduced by Manox at a very young age (sexual abuse, I would call it today) and perhaps by Dereham. However, like may young women today who have suffered sexual abuse at an early age, Katherine was vulnerable to male attentions. She was lonely, unsupervised, not much loved by her family (so it seems to me) and in need of attention. I do think she is the victim in the whole story really.

Good comment !! I agree a young girl craving attention and love very vulnerable ! Timesmay have been different but still human beings with the needs we have today its a shame we can’t find out more and just read in between the lines!! I still wonder if Katherine did have sexual relations with these men why she didn’t get pregnant perhaps she could not have children ?!!!

Katherine certainly has been the victim of cultural perceptions of her sexuality by some writers over the years. However … I’m not sure I really agree with much of this article.

First, whilst it’s maybe worth considering the possibility that not all of Katherine’s sexual encounters were consensual, there isn’t enough evidence to support the assertion made here that she was the victim more than once of potential rape or least assault.

Katherine’s description in her confession to Cranmer of Dereham’s actions also fits comfortably with contemporary ideas of female ‘passiveness’ – it was in Katherine’s interests to highlight this and thus portray herself as the non-active party. But that doesn’t indicate that she meant rape by this – presumably if she had, it would have been in her interests to have said so more explicitly at this stage. Moreover, most of the eyewitness evidence from those in the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk’s household suggests that there was a fairly lax atmosphere with indiscretions taking place in full view of others. It’s not easy to imagine the other girls all sitting around in their beds at night while Katherine was being ‘raped’ by Dereham. As it was, no one else supported this idea. If it had been true, surely someone would have said something. It wasn’t as if people felt they had to protect Dereham’s name after all.

I also don’t agree with the author’s suggestion that Katherine wouldn’t have had relationships in her teens because that would spoil her chances of making a good match as a noblewoman. First, teenagers from whatever background often don’t toe the line in terms of doing what is expected of them, either now or then, particularly if they’re living away from home and close supervision. I should think it’s likely that some girls and women from the same (or better) background as Katherine did likewise and never got caught.

Second, while Katherine was a Howard, she was a younger child of a younger son of the family – just one of many Howards. Her father was allegedly somewhat feckless and passive, so this wasn’t a man like Thomas Boleyn who used every opportunity to advance the prospects of his children. Doubtless she would have married ‘well’ into the gentry or minor nobility, but she wasn’t a big prize on the matrimonial scene, which makes her marriage to the king all the more extraordinary, both to our eyes and those of her relatives at the time. I don’t think any of her sisters made particularly prestigious matches either.

Given that we don’t know Katherine’s year of birth (many recent historians seem to espouse it being nearer 1525 in order to further their point of her being a victim of abuse), that makes it even harder to work out what the situation would have been like for her when she became involved with Manox, Dereham and the king. I’m inclined to think that she was born nearer the earlier estimate of 1520 than 1525 and that her involvement with Manox might be what we would now consider ‘abuse’, but that her relations with Dereham were consensual.

I also think it’s very unlikely that her meetings with Culpeper in 1541 involved nothing more than late-night chats. The amount of risk and subterfuge involved in arranging the meetings was considerable – that’s a huge amount of danger to be putting yourself in, and one would imagine it would only be worth doing if the reward was something otherwise unattainable in broad daylight.

Katherine and all of the other wives of Henry the 8th were trafficed. I agree with Conor Bryne’s research and am glad that he is bringing this to our attention. To have an interest in The Wives while at the same time get pleasure in their ultimate marginalization to me is abhorrent and shows a great lack of humanity.

It’s an interesting theory the person who’s really to blame is her step grandmother in whose care she was, she ultimately failed her, but she was risking much to agree to meet Culpepper after she was Queen, I believe that she did commit adultery with him, two young attractive people meeting alone only means one thing, it’s just very very sad that she lost her life because of it, I think Henry should have been merciful towards her, he should have taken into account her youth and unconventional upbringing, he was nearly thirty years older than her, poor girl didn’t deserve to have her head cut off.

Interesting article (and book, BTW), but I’m not quite convinced — at least not on the part of all three men. (Manox may have been a predator, but I think Dereham was consensual.). First, most of the evidence indicating force is when Katherine has a motive to lie; I’m not sure why she should be considered more credible when trying to avoid disgrace and execution than anyone else would be. She never mentioned any such thing at any earlier time, even when Dereham first sought employment; at that time, Henry would cheerfully have him executed if she had requested it (she could have complained that he had tried to seduce her — which is why she wants him punished — while claiming she resisted). Another historian has stated that Elizabeth could have complained about Thomas Seymour’s behavior if she had wanted to … this seems to militate against the idea of the pervasive sexism forcing submission to rape — if Elizabeth could have complained, why couldn’t Katherine? Katherine didn’t have the additional problem of being the daughter of someone perceived as an evil temptress.

I am currently reading this book. I had gotten it from a tradr site, and the person that sent it was nice enough to send five other books on the Tudors

[Edited]

It is not appropriate to discuss legal cases on here along with people’s names and contact information. This comment has no bearing on the case of Katherine Howard.

Whilst it is always interesting to read new perspectives on historical people and situations, I’m afraid I cannot agree with this author.

First of all, although wonderfully detailed and researched, the historian’s article and general work (ive read quite a few pieces from this gentleman) reads like a history student’s essay or dissertation. Its very balanced and researched, with his opinion wrote up in the conclusion. Quite like how I was instructed to write essays at university. It lacks the fluency and confidence of a bona fide historian such as David Starkey or Eric Ives, who always take a strong stance with their opinions and never try to sit on the fence.

Secondly, although well meaning, I think this gentleman is trying to take 21st century notions and place them into 16th reality. I believe that ideas such as rape and coercion were less stringent back then than they are now. If we read about a fifteen year having relations with older men we automatically think they were coerced or pressured into it. But girls were brought up to be more mature back then and I don’t think a ‘nobody’ like Dereham or Mannox would have dared tried to rape a lady of the Howard family, no matter how lowly she was in that family. Imagine one of her friends had reported it or her aunt had walked in on such a public rape?

Finally, as said above, I cannot imagine that such a public rape would not have been commented upon or brought up by Katherine herself during her investigation. From everything I have read, a lot of people in her dormitory were well aware of the very public and seemingly reciprocated and affectionate relationships between Katherine and particularly Dereham.

Although an interesting read, I think the gentleman is trying to enforce 21st century values on to a 16th century situation and it just doesn’t mesh for myself and seemingly some others. None the less, it has certainly been an entertaining read 🙂

What a pleasure to read what many of us have always known to be true in such a logical way. This has really made my day, so many thanks. Nothing makes me more upset than posthumous slander and if just one more person alive today no longer interprets Katherine Howard as a “lusty wh*re” or some such patriarchal description, then that’s a tiny victory.

Stephen Gardiner introduced Henry VIII to Katherine at one of his parties, were there any repercusions for him considering Katherine’s alleged past love affairs? I wonder if Henry blamed him in any way. You cover such intriguing history.

People often judge the past by the standards of today. No doubt it was a violent time and life was short. I would like to know Katherine’s personality before passing any judgment on her. Depraved as a child – possibly. A wallflower in social settings? A young women thrown into a marriage with a king past his prime and unable to openly express her needs and desires. Was she a girl that liked to flirt with danger? Then throw Henry into the mix. Legs with ulcers and paranoia setting in while he eats his way to immense girth. Possibly low self esteem from being unlucky and not able to believe he has undergone so many injuries. Lashing out at anyone in his way. No doubt kings were narcissistic from the way they were raised. There is a lot of if’s.

Wow! I’m really surprised at how many people here are not open to looking at the 16th century in a new and possibly more realistic light. I happen to be reading this book now (not too far along) and I’m enjoying looking at 16th century relations between people as people, not fairy tale/”official” characterizations. Yes things were different then, but as we all know; the more things change, the more they stay the same. I don’t know if I’ll completely support the author’s theories but I like seeing things from different angles.

Also, I’m not a person who thinks every coercion is rape, but I’m bothered at how people still like to assume a woman who says she was raped doesn’t know what she’s talking about. Rape can mean brutal, screaming abuse (that no one would argue with) but it can also mean a hundred different ways, more subtle ways, that people push others to get what they want.

Isn’t it odd? There is resistance to “looking at the 16th century in a new and possibly more realistic light”, but at the same time, there have been a few disturbing remarks made in these comments about women “lying” about rape–it make me worry about how many modern people are obviously channeling 16th century views….

Good article and the book also brings us a Katherine that was an active Queen in all the senses of the word. There is room for thought when it comes to her earlier relationships especially with Mannox who was hired as her music teacher. Whether above the age of consent (14 plus) or around that age, there is no excuse for abuse or rape by any man on any woman! Mannox was hired as a teacher; he was therefore in a position of trust and authority, and he used that to manipulate Katherine. She was still young, no matter at this time whether we believe she was 12-13 or 14-15 and would have been just awakening to her sexual feelings, confused and overweolmed by the attentions of an older man. Mannox abused his position, whether or not the encounters with Katherine were consensual or not and should have at the very least have gotten his marching orders by the Duchess the first time he took advantage of his pupil. In America, in most states if the sexual relationship is between an adult over 18 and anyone younger who are not married, even if it was consensual, the law states that the younger person is too young to consent and it is statutary rape.

Given that American law originated in England, I am guessing that we had such a law here at one time; after the age of consent was raised in the 1860s to 16. Traditionally many authors have set the age of Katherine at the time of her marriage to the King at anywhere between 17 and 19. This would make her about 14 or 15 at the time of her encounter with Mannox. However, Conor and Joanne Denny believe that she was born around 1524 making her a few years younger and that Mannox and Dereham therefore abused her. It is because we cannot pinpoint her date of birth that the debate rages and will continue to rage until some internal evidence of some document gives us more clues to her birth or we find a record of her baptism and so a date we can work with. While I respect the work of these two authors; I do not agree with the conclusions and with the date; as it seems that the date is a way of making the facts fit the theories. More evidence needs to come to light.

While I do agree that Mannox certainly took advantage to the point of abuse or at least manipulation, and that the Duchess could have done more to protect Katherine; given that she must have hoped for a gtand match for her granddaughter at some point as she was a Howard; but her relationship with Dereham appears to have been much different. I believe that she was between 15-17 when she had a full love affair with Francis Dereham, a sexual relationship that was consenusal on both sides, there is little evidence that it was not so; and that the two believed themselves to be living as if they were promised to each other. It is a pity that Dereham was nothing but a cad and probably did not see their relationship as being serious. I also think that as the Duchess had other plans; Katherine was to be sent to court to a completely new life; the departure of Dereham for Ireland was one that was fortutious for both Katherine and the family. A Howard would be expected to make a much better match than Frances Dereham.

Whatever her sexual past, one it was clear that the King had an eye for the young lady in waiting to Anne of Cleves it is certain that the Duchess; most possibly the Duke as head of the family and others who were introducing Katherine to the King; decided that she must keep that past quiet. Whether the Duke knew; her grandmother did; and silence was the order of the day as Katherine was most likely groomed on how to behave at court; at the banquets that traditon has it she was taken to at Stephen Gardiner’s palace; and when the King began to play court to her. I believe that Katherine had a choice in the matter of marriage to the King; and at first she may not have even been intended as anything more than a distraction. But I also believe that things changed once it was clear Henry was serious and may be looking to her for a new wife; she was overwhelmed by a sense of family duty and pride and by the kings gifts and attentions to her. She may have been told it was her duty to marry the King, but she may also have been flattered. Even fat and obese; Henry was the King and he was still impressive. As Queen she would still have a powerful role to play; and she cannot have been unaware of that fact.

But I also think that Katherine saw the reality of her marriage and wanted some fun. She found Thomas Culpepper attractive and was flattered by his attentions. She sought his company because she was young. She was not an air headed bimbo; she was a young woman who had a great capacity for genuine warmth. She appears to have had a kind heart; she interceded for at least two of Henry’s courtiers and saved their lives. She also showed personal concern for Margaret Pole in the Tower and provided her with warm clothing and with other things of comfort. She accepted Henry’s attentions and she enjoyed the almost daily round of dances and fun at court. But there were times that she was left alone when the King was ill, sometimes for several weeks; she became lonely and looked for companionship. May-be she was a bit nieve and others played on that. Culpepepr was also a cad. He took advantage and Katherine fell for him. Whether of not the couple actually had sexual relations is not entirely clear; but the two did admit to spending long hours in conversation and Culpepper admitted to wanting to go further. Dereham was accused of wanting to replenish the old relationship with Katherine. Again it is not clear if the two did or not.

However, if Katherine and Culpeper did enter into a full blown sexual relationship then it was foolish and dangerous but it was not one of abuse. Katherine was a woman; a young one but old enough to know what she was doing and to accept the consequences. May-be her earlier encounters had made her feel that she needed to give herself to these men and may-be they took advantage of her sexual past. However, it is really difficult to know how to rate her level of consent; given that we really cannot say how old she was. I doubt that she was as young as Conor suggests as Henry would not have married her at that age. I believe she was at least 17/18 when she married the King and that her relationship with Dereham was consensual.

I just wanted to add that when Katherine was finally interviewed by Cranmer that she was in a highly emotional state and it took a long time to piece together what had happened and for the ‘truth’ to emerge regarding her earlier background. I put ‘truth’ in inverted commas as it depends on how you view what she said as to what are the facts. What did emerge where the two main relationships with Dereham and Mannox, which are controversial given the circumstances surrounding them. As I have already stated Mannox abused his position and took advantage of Katherine and maybe even other girls in the household. The Dowager Duchess should have been much more astute in the people that she allowed into her household and to keep better control of the comings and goings in the Maidens Chamber at night. She also should not have trusted these so called tutors to be alone with her grand-daughter, especially after the first instance when he stole a kiss. At that point I would have hauled his arse out of there and down to the authorities and had hiim banished or locked up; as she most probably had the power to do so. Why did she not make some form of complaint about the behaviour of a person of trust she had let into her household?

The answer is given to us in the book and in other books; because the woman was given the blame and it was Katherine who was punished and not Mannox, although he was clearly dismissed at some point. The gender inequalities and expected roles of the time led to Mannox’s abusive and controlling behaviour being overlooked or Katherine being punished for ‘leading him on’; this is not acceptable and even then a more astute and caring person would have taken action to get rid of Mannox.

The picture of Katherine’s relationship with Dereham that emerged at her interrogations is a complex one. As Conor has pointed out in her letter to the King which must be based on her answers to Cranmers questions Katherine says that Dereham forced her and was vindictive in the way that he did so: she claims that she was raped. This is an astonsishing claim for the time and a brave one. Although there were laws against rape; in many cases the claims were hard to prove and the couple in some instances were even advised to marry. Rape could be punished, but the word of the woman was not always taken at face value due to the construct in which women were seen as more sexual beings and seductresses than men. Having said this, a noble woman or gentle woman would have more success in making a charge and bringing a case and families did insist that their daughters attackers were hunted down and punished; or that the case was taken seriously.

Conor has pointed out that here the authorities; that is the royal council gave more weight to the claims of Katherine’s co-accused or those who had given testimony against her; especially the men, than what Katherine had to say. But there is a difficulty with her testimony; it is in contrast to her earlier confession in which she also stated that she had a love affair with Francis Dereham. She describes them being together and the gentlemen coming into the chambers and they were entertained with shrawberries and wine and so on; and this makes for a heavy miix of flattery and sexual activity. She also describes much of the detail of them making love and that they appeared to have seen each other as promised to each other. Now, given that Dereham was a cad, this may have been a way of getting Katherine to sleep with him; laying together and then promising to be man and wife. Katherine also describes him bringing her gifts and the affair went on for a long time. It is only when pressed and distressed and may-be in fear for her life that she says that he in fact raped her. Perhaps now at last we have the truth but Katherine was too afraid to say what Dereham was up to for fear or not being believed. It is not easy to decipher at this stage which of her statements is true and this was the problem that the council had; Katherine had given them contradictorary statements. Dereham himself also gives a third version of the events. Although many of his statements agree; he believed that he and Katherine were contracted as they would have been under canon law and so lived as husband and wife. Katherine agreed that they called each other this; a bit like a pet name; but she also said that she did not believe it was a contract. Ironically had she done so it would have saved her life.

As I have stated before: I do not believe that the relationship with Dereham was anything but consensual; I believe that they had a healthy teenage sexual affair and they both saw each other in the light of having a relationship that was growing stronger, but Katherine realised that for family honour she could not commit to marriage to Dereham. That does not mean that Dereham did not take advantage of this situation,leading Katherine to believe his promises when he had no intention of acting honourably. I also believe that Dereham had high hopes of using his former contact with Katherine to gain access to her household and to bully his way around the court, boasting and making trouble. I also believe that he hoped that Katherine, alone for many weeks when Henry was depressed or his leg hurt and he was ill; would find a soft spot for him and take him back into her life. We do not know if she agreed to do so; it seems that from both testimonies that things did not get that far, although Dereham may have wished they had. Dereham was succeeded in her affections by Thomas Culpepper, who in truth, had no better aims and character than Dereham had. It is not clear that Culpepper and Katherine had a sexual relationship. but by meeting late at night they certainly had a dangerous one.

I believe that the most mitigating factor in Katherine’s actions was loneliness and immaturity. King Henry’s court must have been one of older people than Katherine for the most part; she would have had few peers of her age. Her husband was aging and ill; unlikely to be able to give one so young the energy and attention she would have desired. Being at an age that most people plunge into actions without thought of consequences she probably never thought she would have to answer for her affair with Culpepper and most probably thought whatever happened before her marriage would never carry any weight. It must have been a shock to her when she learned there were people willing to speak against her. At that age, you just do not believe anything bad can happen to you. I have always had a great deal of pity for her; she was just an immature girl trying to navigate in a world she was not ready to live in. Henry should have divorced her and banished her rather than kill her.

Even if Katherine was young, she knew that Henry had already had one wife executed for adultery. So she could not have thought that she would not have to answer for the affair with Culpepper unless she was totally stupid. Maybe she was. Or maybe Lady Rochford persuaded her so.

Katherine was certainly stupid as she denied pre-contract with Dereham which would have meant that she was not married to Henry. Of course, she had no legal counsel to advice her.

Of course Henry should not have killed her. Other kings did not kill their unfaithful wives and unlike Anne, Katherine was not accused for planning to murder him. But with Henry’s psychology, public humiliation was too much to bear.

He had brought the fate to himself by marrying a young girl who suited to a mistress but not a queen.

Hi everyone,

Thank you for all your comments. I just wanted to step in here because I’ve had to remove one comment regarding a specific case of alleged rape and I’m concerned about a couple of other comments regarding women lying about rape.

We don’t know what happened in 1541 or when Katherine was living at Lambeth and Horsham, we can only go on the records of the interrogations and it is impossible to know whether those are accurate. Most of us accept that Anne Boleyn was framed and that she was innocent, and we don’t believe the indictments of 1536, but many are willing to take as fact the records from 1541 about Katherine.

All any historian/researcher/author can do is to interpret the evidence, look at the context and then come to a conclusion, which is still going to be opinion based. While I don’t agree with all of Conor’s theories and thoughts on Katherine’s situation, he can back his theories up. We cannot say that Katherine was not abused, manipulated or raped. It is a theory which is not only believed by Conor, but also by historians like Retha Warnicke, so he is not alone.

Just because one modern woman might have lied about rape (I’m addressing one particular comment here), it does not mean that other women lie and it does not mean that Katherine was not raped.

I have received a couple of emails about how some of the comments here seem to promote a rape culture, and that upsets me. You are all entitled to your opinions and to share them, but please bear in mind other users of this site, women who may well have been abused, treated badly, raped etc. and who have been too scared to report it or who were not believed. All debate is appreciated but comments need to be sensitive, particularly on issues like this.

I don’t want to offend or upset anyone and I appreciate people taking the time to read articles on this site, and I know guest authors appreciate it too. I love the fact that I can post something on here and immediately get feedback on it and have such wonderful stimulating discussion. Thank you for reading this and bearing what I say in mind for the future.

Perhaps the relationships between Catherine and Dereham and Catherine and Culpeper were abusive and perhaps Dereham raped her, but I think it is unfair on both men to take that theory/speculation as fact, when there is no evidence to support it other than the terrified comments of a young women facing a dreadful death. We can’t say one way or the other, just the same as we can’t say with certainty that George Boleyn wasn’t a wife abuser, or that Anne and George Boleyn didn’t commit incest. The contemporaneous sources/witnesses don’t support what Catherine said in her evidence, just as the primary sources don’t support the incest allegation. So shouldn’t Dereham and Culpeper be given the benefit of the doubt in the same way as we do Catherine, Anne and George?

I’ve seen comments that it is awful to defame the dead i.e. Catherine, but aren’t we doing exactly that by labelling Dereham and Culpeper as abusers. It’s an interesting theory, fine, but in a civilised society we judge guilt ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’. I don’t see that here, just as I don’t see that George Boleyn was an habitual rapist and abusive husband who ‘probably’ subjected his wife to unnatural sexual practises (Weir, ‘The Lady in the Tower’).

Claire:

There have always been a couple of inconsistencies in Catherine’s sad life that have bothered me and have always made me question the perception that she could not control herself.

I cannot remember where I read it but I remember reading that Catherine believed the King was so powerful and being Head of the Church, he had the power to know what one said to the clergy while in the confessional. I am not sure if this is 100% accurate as it has been a long time since I read this comment, but it always bothered me. If this comment was true and something that can be attributed to her, why would she act in such a way that the King would not approve of.

I remember also reading somewhere that unlike Anne Boleyn, she did not have much education and had difficulty in reading and writing. Again, I can’t remember where I read this and not sure if it is accurate, but it would stand to reason that she would be in awe of someone all powerful like King Henry (even when he was old and bloated). It is clear that the portraits of the King, even at that time show him as powerful. If they are accurate, I would imagine he would be one of those people who walk in a room and everything stops because he commands the room with his charisma, based on the accounts by all types of individuals throughout his reign. I

n addition, when Catherine was being interrogated and tried to give her a chance to save herself by saying that she was Dereham’s wife (and could not be legally married to the King), she refused to take that way out.

Of all the players in this tragedy, why did Henry subject Dereham to the traitor’s death? He could have commuted his sentence to beheading like Culpepper’s (whom he seems to have had a regard and affection for) but he did nothing which leads me to believe that Henry believed that Dereham had ruined or spoiled Catherine and he was going to make him pay for that.

I sometimes wonder if the King would have let her live but the Council convinced him that if she did not confess that she had been through a form of marriage with Dereham, she would have to die or it would appear that the King condoned her behavior.

The saddest part of the tale is how it appears that no one in her family tried to step in and help her. Everyone seemed to be too concerned with placing blame on others and saving their own skins.

Catherine says Dereham had raped her but I don’t understand why she allowed him back into her service unless of course he was blackmailing her, he seems a rather unsavoury character anyway, he had been a pirate in Ireland and seems a bit of a hot head, Culpepper was pardoned for the rape of a woman from the lower classes, I find it shocking that he had the high position of being Henrys personal attendant, the pair of them shouldn’t have been in court in the first place, I never knew Catherine had accused Dereham of raping her I m just wondering if it was a desperate attempt to save her life as she was hysterical by then, they found the letter from her to Culpepper which totally damned her, then as now no one should ever write notes as they are evidence, Culpepper should have destroyed it but he hadn’t the sense, Mary Anne’s right about her family deserting her, the Howard’s coerced Catherine into marrying the King but they left her to the wolves when they found out about her past, the Howard’s were a very ambitious family as they believed they had a claim to the throne all they could do was lie low and try to keep their heads on their shoulders.

What made the Howards believe they had a claim to the throne?

They were descended from Edward 111.

Until the reign of Edward IV the Howards were a relatively insignificant Suffolk family made up of lawyers and members of parliament, and actually owe all to their Mowbray connections. True, earlier Mowbrays had married granddaughters of certain kings, but this was of little or no importance in the pecking order for the throne. The main royal connection the Howards had through the Mowbrays was to King Edward I, who died in 1307, much too far away in both time and blood to give the Howards any claim in the reign of Henry VIII.

I had not heard of a Howard family connection to Edward III – very interesting.

I think I’m in error I heard some where the Howard’s were a very arrogant family who believed they were more royal than the Tudors, I could have mixed them up with their Plantagenet cousins Cardinal Pole and his mother the Countess of Salisbury but the Earl of Surrey did like to flaunt his Royal connections by having the Arms of England quartered with the Howard Arms, and they did like to marry members of the family into Royalty.

Hi Christine,

I had a go at looking up an Edward III/Howard family connection last night, but

with no success.

It’s very true what you say about the family’s arrogance, and Katherine’s cousin Surrey certainly looked down on those he saw as ‘the new erected men’ at the court of Henry VIII, forgetting that a mere 60 years earlier the Howards themselves were similarly ‘new erected’.

The business with the heraldry that cost him his life could have stemmed from his snobbery, but actually he did have the right to bear the arms of Edward the Confessor, a privilege granted to his ancestor Thomas Mowbray by Richard II because of his descent from Edward I, but it was the wrong time to risk the wrath of someone as dangerous and unpredictable as Henry VIII had become.

Hi Marilyn yes it’s their descent from Edward 1st not the 111, all the best, Christine

Yes, Edward I makes sense:

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk was son of John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk (1421 – 1485)

John Howard was son of Sir Robert Howard (1385 – 1436) and Lady Margaret de Mowbray (1388 – 1459)

Margaret was the daughter of Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk (of the first creation), (1366 – 1399)

Thomas was the son of John de Mowbray, 4th Baron Mowbray (1340 – 1368), and Elizabeth Segrave (d.1375)

Elizabeth was the daughter of John de Segrave, 4th Baron Segrave, and Margaret, Duchess of Norfolk (c. 1320 – 1399)

Margaret was the eldest daughter of Thomas of Brotherton, 1st Earl of Norfolk (1300 – 1338)

Thomas was a son of Edward I (1239 – 1307) and his second wife, Margaret of France (c.1279 – 1318)

I’d love for David Starkey to submit a rebuttal to this article, particularly considering his comments on the feminisation of history. In this case, it can be seen that Conor is making the men to be the villains of the piece and excusing Katherine for her indiscreet behaviour (if one is to think along those lines). I’m sure Starkey would be having a field day about it 😀

Interesting ideas but not ones I necessarily agree with.

Even if u don’t agree with someone’s opinion we should still value them as we are all adults !!!

This is a little off topic to the article, but about the person in the article. Is it just me or does she look kind of like Scarlett Johansson? Also no one can really know what happened for sure since there are so many points of view. All people can really do is speculate what happened.

That’s who that painting reminds me of! I was trying to figure that out. Thank you!

Yes she does resemble her

Hi everyone, thank you so much for taking the time to read this article and submit comments putting forward your opinion of the argument.

I would firstly like to point out that neither here, nor in my book, do I actually state with certainty that Katherine was a victim of rape and sexual abuse. It is not certain and it would be foolish to state that she was as a matter of fact. Rather, I suggest the possibility that she was. Historians have almost always portrayed her relationships as consensual and voluntary, but there is sufficient evidence to indicate that not all of them were.

I can understand why people agree that Manox probably abused her, but are less sure about Dereham and Culpeper. My reason for believing that the relationship with Dereham was also not consensual follows from the following evidence: none of Katherine’s comments indicates she enjoyed the affair with Dereham, at a time when female virginity was highly prized and its loss was viewed as a heinous matter (Warnicke); Dereham appears to have been an aggressive and ruthless pursuer, as demonstrated by his behaviour at court when he openly bragged of his relations with the queen and swore that he would marry her; Dereham appears to have begun the relationship with Katherine as her protector, meaning that she felt grateful towards him; her testimony describes his “vicious purpose” and “flatterings and persuasions”, which to me indicates that he cunningly persuaded her to have a sexual relationship; lastly, the age disparity between them. We do not know Dereham’s age but he was almost certainly a good few years older than Katherine, who was probably 15 in 1538.

I also take issue with comments by the likes of Jennifer who state as fact that Katherine committed adultery. There is no evidence that she did and if you read my book you’ll see how shaky the “evidence” actually is. Her letter to Culpeper may not even have been written by her and, as Warnicke convincingly suggests, it is not a love letter, once Tudor letter conventions are taking into account. Katherine clearly wished to see him, yes, but what for, we cannot and never will know. I do believe he may have come into sensitive information about her past and was using it to blackmail her into granting him favours. Why do I believe this – well, at the very time he began meeting with her, in the spring of 1541, Dereham arrived at court and began boasting of his past with Katherine. Although there is no evidence that Dereham and Culpeper met, or knew, one another, Culpeper could have heard these scandalous rumours and used it against the queen. He had a reputation for being a violent man, for there were stories that he had raped a parkkeeper’s wife and murdered her husband (although it was possibly his older brother who actually committed these offences – confusingly, they both had the same name).

Vermillion, thank you for your detailed feedback. Katherine actually did accuse Dereham of rape and she referred to his “vicious purpose” and “subtle persuasions”. I agree that it is possible that she was presenting herself in a passive light, but what about Dereham’s own behaviour at court? He aggressively pursued her to court and openly bragged of his former sexual relations with her. He put both of their lives in danger. He even talked about the king’s death, a treasonous offence at the time, and claimed that Katherine would marry him when Henry died. So yes, Katherine may have been presenting her actions in a different light, but Dereham’s own behaviour both before and after her marriage indicates to me that she was telling the truth. Moreover, even if Katherine wasn’t ‘raped’, she may well have been coerced, and the other ladies could have feared the dowager duchess’s reaction if she discovered that her granddaughter was being sexually active. This could have prevented them from informing her. Certainly, when she learnt of Katherine’s experiences, she not hit both Katherine and Dereham but slapped Joan Bulmer. Fear that they would be physically punished, or even dismissed from service, would have prevented other individuals from speaking out.

Vermillion, your point about Culpeper is a good one, but Warnicke puts forward a convincing argument which I agree with: Culpeper had learned about the queen’s past and was blackmailing her into meeting him, with the aid of Lady Rochford, to press her to grant him favours in order to buy his silence. Katherine had to meet him, in these circumstances, to prevent him bringing to light her past. So no, they weren’t having sex – she was trying to maintain her position and even save her life.

Jenny, while my piece does take into account Katherine’s age, I think it’s wrong to suggest that I’m using 21C morals and applying them to the past when analysing Katherine’s relationships at the ages of about 13 and 15. My argument actually relies more on early modern notions of coercion, sexuality and honour, and so pays attention to sixteenth-century mores, not twenty-first century morals. I never say that she was ‘publicly raped’. There are multiple forms of coercion, then as now, and Katherine may have experienced any one of them. Never do I say she was ‘raped’.

I would like people to refrain from posting nasty and personal comments. This is not an anti-men piece, it is not written with a feminist agenda. I have put forward this argument because I believe it is what actually happened. Women have always been abused and

there is evidence that Katherine was.

It is true that we cannot know for sure if Katherine and Culpepper had sex or not, but they had good chances to it, being alone for hours n the middle of the night. No sensible woman who cares for her reputation would have consented to such meetings, and even a less jealous husband than Henry would have thought that such meetings were evidence enough for if not of adultery in deed then at least in heart. Culpepper admitted the intent of both parties and as we know, in Tudor justice that was enough.

However, Cranmer and his witnesses from the Dowager Duchesses’ home had a strong motive to get Katherine off.

Conor great work

“I would firstly like to point out that neither here, nor in my book, do I actually state with certainty that Katherine was a victim of rape and sexual abuse. It is not certain and it would be foolish to state that she was as a matter of fact. Rather, I suggest the possibility that she was. Historians have almost always portrayed her relationships as consensual and voluntary, but there is sufficient evidence to indicate that not all of them were.”

But Conor, you say in your book;-

‘It will here be argued, from a careful reading of the evidence produced in the indictments against a backdrop of early modern views about female sexuality and sexual deviance, that Dereham sexually abused the niece of his master, possibly going so far as to rape her.’

That suggests that you go on to argue that he does. But other than Catherine’s evidence given under extreme pressure and with her being completely terrified, where is the evidence for that? Mark Smeaton, under the same pressure, admitted to having sex with Anne Boleyn on 3 ocasions. We dismiss that in order to give Anne the benefit of the doubt. Should we now reavaluate her guilt?

“My reason for believing that the relationship with Dereham was also not consensual follows from the following evidence: none of Katherine’s comments indicates she enjoyed the affair with Dereham, at a time when female virginity was highly prized and its loss was viewed as a heinous matter (Warnicke). Dereham appears to have been an aggressive and ruthless pursuer, as demonstrated by his behaviour at court when he openly bragged of his relations with the queen and swore that he would marry her.”

He was foolish in bragging of his relationship with her, but how does that make him an aggressive and ruthless pursuer?

“Dereham appears to have begun the relationship with Katherine as her protector, meaning that she felt grateful towards him; her testimony describes his “vicious purpose” and “flatterings and persuasions”, which to me indicates that he cunningly persuaded her to have a sexual relationship; lastly, the age disparity between them. We do not know Dereham’s age but he was almost certainly a good few years older than Katherine, who was probably 15 in 1538.”

Again this simply provides Catherine’s evidence, which seems to me odd terminology for a young woman to use anyway. As for the age disparity, there was a far greater age disparity between her and Henry than her and Dereham. The fact Dereham was older than her doesn’t mean he sexually abused her. It doesn’t follow.

“Her letter to Culpeper may not even have been written by her and, as Warnicke convincingly suggests, it is not a love letter, once Tudor letter conventions are taking into account. Katherine clearly wished to see him, yes, but what for, we cannot and never will know.”

Exactly, we will never know, but I can’t really see the logic in anything Warnicke says. Look at how she interpreted George Boleyn’s scaffold speech; bizarre!

“I do believe he (Culpeper) may have come into sensitive information about her past and was using it to blackmail her into granting him favours.”

Based on what evidence?

“Why do I believe this – well, at the very time he began meeting with her, in the spring of 1541, Dereham arrived at court and began boasting of his past with Katherine. Although there is no evidence that Dereham and Culpeper met, or knew, one another, Culpeper could have heard these scandalous rumours and used it against the queen.”

Could have?

“He had a reputation for being a violent man, for there were stories that he had raped a parkkeeper’s wife and murdered her husband (although it was possibly his older brother who actually committed these offences – confusingly, they both had the same name).”

Conor, in your own book you do not give credence to this story. So if you refute the story, then why are you now saying Culpeper had a reputation for being a violent man?

“He (Dereham) aggressively pursued her to court and openly bragged of his former sexual relations with her. He put both of their lives in danger. He even talked about the king’s death, a treasonous offence at the time, and claimed that Katherine would marry him when Henry died. So yes, Katherine may have been presenting her actions in a different light, but Dereham’s own behaviour both before and after her marriage indicates to me that she was telling the truth.”

I don’t deny Dereham was foolish, and that his bragging put both himself and Catherine in danger, but ‘aggressively pursued her to court’? How can we say that? ‘His own behaviour before and after the marriage’. What behaviour?

“Moreover, even if Katherine wasn’t ‘raped’, she may well have been coerced, and the other ladies could have feared the dowager duchess’s reaction if she discovered that her granddaughter was being sexually active. This could have prevented them from informing her. Certainly, when she learnt of Katherine’s experiences, she not hit both Katherine and Dereham but slapped Joan Bulmer. Fear that they would be physically punished, or even dismissed from service, would have prevented other individuals from speaking out.”

‘May well have’, ‘could have’. It’s a theory based on supposition.

“Warnicke puts forward a convincing argument which I agree with: Culpeper had learned about the queen’s past and was blackmailing her into meeting him, with the aid of Lady Rochford, to press her to grant him favours in order to buy his silence. Katherine had to meet him, in these circumstances, to prevent him bringing to light her past.”

Where is the evidence for this beyond it merely being a theory?

I hope I don’t sound too argumentative, but I just can’t see the evidence for demonising these men.

But then Jane Rochford said she could hear them carrying on behind the door and Catherine wrote Culpepper that letter in which she told him how much she longed to be with him, it a a strange letter to write to some one whose blackmailing you.

Hi Clare, thanks for your points. Don’t worry about sounding argumentative – this topic has been accepted at face value for so many years, so it’s great that people are starting to finally really interrogate what went on and ask questions.

In answer to your points:

Firstly, in my book, I suggested that there was evidence to suggest that Katherine was a victim of abuse. In this article, I put forward similar evidence in line with early modern cultural and social circumstances to explain the possibility of Katherine being abused, in response to some who have questioned whether this was indeed the case. But neither here, nor in the book, do I definitively say: “Katherine was a victim of abuse. This is why she behaved as she did.”, etc. That would be to slip into certainty, for which there is NO evidence. For centuries it has been accepted that she was wanton and promiscuous and committed adultery. I believe that there is evidence to challenge this. Joanna Denny noted this in her own biography of Katherine, so my ideas are not necessarily new. Katherine cannot be definitively regarded as a victim of sexual abuse but neither can she conclusively be identified as an adulteress. The evidence is too insufficient to permit either extreme viewpoint.

“That suggests that you go on to argue that he does. But other than Catherine’s evidence given under extreme pressure and with her being completely terrified, where is the evidence for that? Mark Smeaton, under the same pressure, admitted to having sex with Anne Boleyn on 3 ocasions. We dismiss that in order to give Anne the benefit of the doubt. Should we now reavaluate her guilt?”

Firstly, G.W. Bernard has reevaluated Anne’s guilt and he has suggested that she was an adulteress. His viewpoint may not be agreed with, and many historians have disagreed with him, but Bernard is perfectly legitimate to reassess contemporary evidence and ask new questions. That stops historians being lazy and accepting things at face value just because it’s the accepted belief among scholars. Similarly, I believe that the word of Katherine’s lovers has tended to be accepted by virtually all historians to date. Historians have not considered the possibility that she was telling the truth. She had already brought shame to her family, she was already guilty of an offence, she almost certainly knew that her husband would annul his marriage to her at the very least (and would possibly do more at the very worst); why would she continue to lie and lie? For me, that doesn’t make sense. Accepting that Katherine was lying means accepting that the men were telling the truth. Yet how do we know they were telling the truth?

“He was foolish in bragging of his relationship with her, but how does that make him an aggressive and ruthless pursuer?”

As noted, none of Katherine’s comments indicate she enjoyed his relations with her. She only asked him to come to court at her grandmother’s urging, presumably because Dereham had approached her grandmother and sought her assistance. He wouldn’t leave her alone. She didn’t invite him to court, she left him behind, he brought knowledge of their relationship to light – for what purpose? Why was he continuing to brag about their relations, unless it was, as some historians have speculated, because he was trying to blackmail her? Why was he putting their lives in danger?

“Again this simply provides Catherine’s evidence, which seems to me odd terminology for a young woman to use anyway. As for the age disparity, there was a far greater age disparity between her and Henry than her and Dereham. The fact Dereham was older than her doesn’t mean he sexually abused her. It doesn’t follow.”

But I pointed out in an earlier comment that my argument for Katherine’s coercion doesn’t rely solely on her age. It rests on the evidence of the testimonies and understanding of the early modern culture. When her language is closely looked at, it doesn’t follow that she entered these relations voluntarily – again, why would she have? He was lower in status than her and she was clearly proud of her Howard lineage. She would have been groomed to expect an excellent marriage and a possible career at court. Was she really foolish enough to put all of this in jeopardy? This relies on believing that Katherine was stupid or willing to disobey her family – yet where is the evidence for this? You might not agree with Warnicke but I wholeheartedly agree with her, and I directly quote here: “Finally about Katherine– there is a pattern — abused as a child, taken advantage of by Dereham, and then by Culpeper.”

Clare I can understand why you might think my theory is nothing more than supposition, but I think you need to remember the bigger issue here: everything historians have suggested about Katherine to date is exactly that: supposition. She was guilty of adultery. She was stupid. She led Henry on. She broke Dereham’s heart. She was jealous of Mary Tudor. She was a “juvenile delinquent”. She was unpopular and disliked.

All of these ideas – and many more – are suppositions and speculations, yet historians state them as fact. I reiterate in this that I am not definitively saying Katherine was a victim of sexual abuse. But I am saying that it is possible, and given the scarcity of evidence and the distorted and invented nature of much of what we DO have, I feel my theory is as plausible as any other that has been given to date. Katherine’s own testimony has been ignored or doubted ever since she gave it. Historians have privileged the words of her male lovers over hers. I am suggesting maybe we treat her side of the story with more seriousness than it has otherwise been given.

Thank you so much, Conor! I’m so happy to see Katherine Howard finally getting more scholarly attention.

Conor, thanks for taking the time to reply to this thread. I’d completely agree with you that it’s important not to take accepted historical ‘convention’ as ‘fact’ without necessarily questioning it first.

However, there’s a danger when looking to revise conventional interpretations of going too far the other way in an attempt to redress the balance, something that I’d say both Warnicke and Bernard have been guilty of in their re-assessments of Anne Boleyn. Warnicke’s argument has been convincingly pulled apart since by other historians and Bernard’s had very little foundation to start with other than a ‘hunch’ of his that Anne was guilty, which I would posit is not a legitimate basis upon which to construct an argument that black is white. Without concrete new evidence, on which very little on the Tudor age has emerged in recent years, it’s just a case of reinterpreting the same few facts that do exist, but often to the point of absurdity.

I’m not familiar with Warnicke’s argument on Katherine Howard, but given her past form I’d tread very carefully around any new theories she is advancing. It’s also worth noting that Julia Fox came to an entirely opposite conclusion in relation to what was going on between Katherine, Thomas Culpeper and Lady Rochford in her attempt to rehabilitate the latter a few years ago. I didn’t find Fox’s argument very compelling as again it was full of the ‘what if’s, ‘might have’s and ‘it could be argued that’s which bedevil such revisionist history – there was almost no substance to attach to the supposition – but it goes to show that it’s possible to come to wildly different conclusions from the same starting point if the chief starting point is ‘other alternatives are possible’. There is a big step between saying that one theory is possible in terms of it not being impossible, given the amount of time that has passed and lack of primary evidence that exists and which I think we’d all accept, and then going on to say that it is just as possible as any of the other interpretations or even more possible – that is going far too far in my opinion. To do so, you’d have to argue that every interpretation of every piece of primary evidence is incorrect, which is stretching things to put it mildly.

I don’t think that the idea that Katherine was a ‘slapper’ to use modern parlance is commonly accepted by all historians these days in any case. Lacey Baldwin Smith’s study was published in 1967 so is informed by very different cultural ideas (I see in your footnotes that you give the publication date as 2009 as if it’s recently published, but that of course is the republication date, not the original publication date) and there hasn’t been a full-on study of Katherine since (although I note that Gareth Russell is in the process of writing one, so will be interested to see what his take is). Joanna Denny’s book on Katherine, like her book on Anne Boleyn, is a strange piece of writing that verges on the polemic at times. From what I’ve read, Katherine isn’t universally condemned for having a sexuality anymore – but she is considered to have agency, not to have been ‘coerced’ (whatever that might be intended to mean – to my mind it’s a problematic terminology as it encompasses a whole range of forms of behaviour) in every situation in which she found herself.

To Vermillion:

I think that you a make really good point: many interpretations are possible (or rather not impossible), but that does not mean they are *likely*.

“Firstly, in my book, I suggested that there was evidence to suggest that Katherine was a victim of abuse. In this article, I put forward similar evidence in line with early modern cultural and social circumstances to explain the possibility of Katherine being abused, in response to some who have questioned whether this was indeed the case. But neither here, nor in the book, do I definitively say: “Katherine was a victim of abuse. This is why she behaved as she did.”, etc. That would be to slip into certainty, for which there is NO evidence. For centuries it has been accepted that she was wanton and promiscuous and committed adultery. I believe that there is evidence to challenge this. Joanna Denny noted this in her own biography of Katherine, so my ideas are not necessarily new. Katherine cannot be definitively regarded as a victim of sexual abuse but neither can she conclusively be identified as an adulteress. The evidence is too insufficient to permit either extreme viewpoint.”

May I start by saying I agree that Catherine’s reputation should be challenged and reconsidered. There was far more to the young woman than has previously been considered or given credence to. I do not consider her to be a wh*re or any other of the unfortunate names she has been subjected to. I also believe she was innocent in that she and Culpeper had not actually committed a sexual act. I agree there is evidence to oppose the view of Catherine as wanton, promiscuous and guilty of adultery. That was not the point I was making. It was the demonising of the men I object to. I appreciate your views are not new and that Denny and Warnicke have already raised allegations against them but again I say that other than Catherine’s evidence at the time of her arrest there is no evidence that she was abused or raped or blackmailed.

“Firstly, G.W. Bernard has reevaluated Anne’s guilt and he has suggested that she was an adulteress. His viewpoint may not be agreed with, and many historians have disagreed with him, but Bernard is perfectly legitimate to reassess contemporary evidence and ask new questions. That stops historians being lazy and accepting things at face value just because it’s the accepted belief among scholars. Similarly, I believe that the word of Katherine’s lovers has tended to be accepted by virtually all historians to date. Historians have not considered the possibility that she was telling the truth. She had already brought shame to her family, she was already guilty of an offence, she almost certainly knew that her husband would annul his marriage to her at the very least (and would possibly do more at the very worst); why would she continue to lie and lie? For me, that doesn’t make sense. Accepting that Katherine was lying means accepting that the men were telling the truth. Yet how do we know they were telling the truth?”

Of course an historian should challenge and not take things at face value. Bernard was entitled to his view point, but ultimately we need to look at, not only what people say in times of extreme stress, but at the evidence as a whole. That’s why Bernard’s viewpoint has never been particularly successful ( I sometimes wonder whether he actually supported his own argument or whether he was simply putting forward a ‘what if’). Of course it’s possible Catherine was telling the truth, just as Smeaton may have been. But there is no corroborative evidence, and in fact in Catherine’s case the other evidence refutes what she said.