A big welcome to author Toni Mount who is visiting us today on the final stop of the book/blog tour for her debut historical novel The Colour of Poison: A Sebastian Foxley Medieval Murder Mystery. It’s a wonderful novel and if you’d like to be in with a chance of winning a paperback copy then simply leave a comment below saying what magic potion you’d like to concoct. Leave it before midnight on Friday 6 May. A winning comment will be picked at random and the winner contacted by email.

A big welcome to author Toni Mount who is visiting us today on the final stop of the book/blog tour for her debut historical novel The Colour of Poison: A Sebastian Foxley Medieval Murder Mystery. It’s a wonderful novel and if you’d like to be in with a chance of winning a paperback copy then simply leave a comment below saying what magic potion you’d like to concoct. Leave it before midnight on Friday 6 May. A winning comment will be picked at random and the winner contacted by email.

Over to Toni…

In The Colour of Poison, Gilbert Eastleigh isn’t just an apothecary. Behind closed doors, he dabbles in alchemy and sorcery. Such practices were supposed to be illegal but it’s known that kings encouraged alchemists – as King Edward does in the novel – in the hope that they really would discover how to turn base metals into gold, or uncover the secret of immortality. Either way, it involved the use of the mythical Philosopher’s Stone. So, what did alchemists and sorcerers do in their gloomy, secret dens?

From the preparation of exotic potions, as you can imagine, it was only a small step to the mysterious art of alchemy. In fact, many of the apothecary’s standard procedures, such as distillation and evaporation, were used by alchemists – and, later, scientists – in their experiments, in pursuit of the elusive philosopher’s stone, which would turn base metals into gold, and the elixir of life which would restore health and bestow eternal life. In medieval times, there seemed no reason to doubt these things were possible.

Though much of what alchemists did was the foundation of modern science, they liked to disguise their knowledge and results – or lack of – in weird, symbolic language, making sure only the truly initiated would understand what they meant. It was also a matter of self-preservation: because one of the basics was to be able to make gold, all monarchs had to beware of some lowlife secretly manufacturing gold, either to get rich quick himself, or to finance the enemies of the monarch. Therefore, all alchemy was outlawed, unless sanctioned by the monarch. A sensible alchemist made sure the king was on his side.

One such was George Ripley, born at Ripley, near Harrogate, in the early fifteenth century. He studied alchemy and related subjects in Rome, Louvain and on the island of Rhodes. While on Rhodes, he created gold for the Knights of St John, giving them £100,000 a year – so he claimed, but of course the process was far too involved and secret to be divulged openly. In 1471, George was a canon at Bridlington Priory where it was noted how the fumes and stink from his still-room (laboratory) annoyed the prior and brethren of the community. He wrote books on the alchemical arts: On the philosophers’ stone and the phoenix was a rewriting of earlier authors from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, so not too controversial, but his Compound of alchemy or the twelve gates leading to the discovery of the philosopher’s stone, the first alchemical text written in English in 1471, was dedicated to King Edward IV, just to be on the safe side, and his Latin Medulla alchemiae or the Marrow of Alchemy of 1476, was dedicated to the Archbishop of York. The twelve gates were the various chemical techniques then known e.g. calcination, condensation and sublimation. To give you some idea of the lengths to which an alchemist would go to disguise his secret formulae, this is Ripley’s colourful description from his Compound of alchemy of the making of the elixir of eternal life – the alchemists’ other goal – complete with a zoo full of metaphorical creatures:

Pale & black with false citrine, imperfect white & red,

The peacock’s feathers in colour gay, the rainbow which shall overgo,

The spotted panther, the lion green, the crow’s bill blue as lead,

These shall appear before the perfect white and many other mo’e.

And after the perfect white, grey, false citrine also,

And after these then shall appear the body red invariable,

Then hast thou a medicine of the third order of his own kind multiplicable.

Apparently, the green lion symbolises the element mercury, the lion often being referred to as ‘devouring the sun’ i.e. gold, and mercury will dissolve gold (and silver) to form an amalgam which can be used for gilding other metals. The alchemists believed mercury was the element, a component of all other known metals which made it possible to turn them liquid when heated. Because it was so important, it was symbolised by the most illustrious animal: the lion, but why green? I haven’t been able to discover, as yet. Mercury was also known to alchemists as the doorkeeper, May dew, mother egg and the bird of Hermes, to name a few.

When George Ripley died c.1490, he was rich – far richer than a humble canon ought to be – so folk believed he must have succeeded in making gold but, on his deathbed, he confessed to having wasted his whole lifetime in fruitless pursuits, urging that his writings should all be burned, seeing they were merely speculation, not based on valid experiments at all. Of course, his books weren’t destroyed. After all, George had got rich by some means and, if not by alchemy, then how?

Thomas Norton was a Bristol man from a respected family: his grandfather had been mayor of Bristol. Born c.1433, Thomas did a kind of correspondence course in alchemy with George Ripley and, aged 28, spent forty days studying at Ripley’s side. Thomas was supposed to have succeeded in making the elixir of life – twice – only to have it stolen from him, once by a servant and once by the wife of neighbouring Bristol merchant. According to his great-grandson, Samuel Norton (also an alchemist), Thomas was a member of Edward IV’s privy chamber. This is quite possible. Edward certainly took a serious interest in alchemy, probably because the manufacture of gold would have done his ever-depleted coffers a world of good; he may even have ‘dabbled’ himself. In 1477, Thomas published a book called the Ordinal of alchemy which was still in print in 1652 but he didn’t dare declare his authorship openly, concealing in name encoded in a cipher. But in 1479, Thomas accused the then mayor of Bristol of treason. In the course of enquiries, Thomas’s own life came under examination and was found to be anything but blameless: he frequented taverns, skipped church and played tennis on Sundays. The charges against the mayor were dropped; the accusations of a back-slider like Thomas would not have carried weight in court.

Toni Mount earned her research Masters degree from the University of Kent in 2009 through study of a medieval medical manuscript held at the

Toni Mount earned her research Masters degree from the University of Kent in 2009 through study of a medieval medical manuscript held at the

Wellcome Library in London. Recently she also completed a Diploma in Literature and Creative Writing with the Open University. Toni has published many non-fiction books, but always wanted to write a medieval thriller, and her first novel The Colour of Poison is the result. Toni regularly speaks at venues throughout the UK and is the author of several online courses available at medievalcourses.com. She also teaches a very popular course in The History of Science.

The Colour of Poison is published by MadeGlobal.com and written by Toni Mount. Here are more details:

The narrow, stinking streets of medieval London can sometimes be a dark place. Burglary, arson, kidnapping and murder are every-day events. The streets even echo with rumours of the mysterious art of alchemy being used to make gold for the King. Join Seb, a talented but crippled artist, as he is drawn into a web of lies to save his handsome brother from the hangman’s rope. Will he find an inner strength in these, the darkest of times, or will events outside his control overwhelm him?

Only one thing is certain – if Seb can’t save his brother, nobody can.

The Colour of Poison is available as a paperback or kindle book. It is a great read and you can click here to find out more about it.

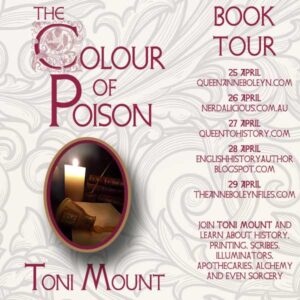

Here is the schedule for Toni’s book/blog tour if you’d like to catch up on the other stops and giveaways. Click on the image to enlarge:

Felix felisis from Harry Potter!

Draught of Peace!

Serum of health

A excellent wish.

A restoration potion

A potion that prevents Alzheimer’s

Esther Sorkin

And cures.

I wish I knew how to make a potion that would allow me to read people’s thoughts whenever I wanted or a potion of truth that would make people tell the truth when I asked them what I would like to know! 😉

I would like a potion that would enable me to be in two places at the same time

Health Potion

A potion for happiness!

potions I love potions and magic and have always wanted to be a real alchemist or apothecarist. I have always seen myself as a Severus Snape type working in a dungeon making potions to save people and animals from horrible diseases like Cancer and neurodegenerative things as well as making perfumes and divine smelling mysteries.

A potion that would make people kinder and nicer to each other.an elixir that would make a nicer people.

I love medieval mysteries! I should like a potion to turn evil into good and meanness into kindness. I don’t need gold or jewels or to be young again.

A potion to keep people in their place.

I would love to have a poly juice potion to figure oUT how my husbands mind works; )

A potion that cures cancer.

A truth potion for politicians would be fantastic

The book looks very intriguing. Having just gone through 7 solid weeks of poorly children, I would love a potion to keep them well!

A potion that would enable the drinker to see another person’s real motivations would be good, to prevent being talked into doing things that are not good for the drinker!

I would like a potion for cancer and all diseasess.

I’d like a potion that eleminates the need to clean–housekeeping is not my forte!

A potion to be able to talk to animals.

How about a potion that keeps babies, babies! (just a little bit longer~ mine is growing way to fast!)

I’d like to make a potion to resurrect the dead.

I’d make a potion that gives me the benefits of sleep without actually sleeping.

I’d love to have a potion that would allow me to have conversations with my pets and other animals.

Something to fix fallopian tubes and make u fertal so that you may have a baby

Would love to know how to make a potion that would let me spread kindness.

I would love a potion that enabled you to travel anywhere in seconds.

I would love a potion that made everyone happy, to remove the stresses and strains of life.

There are so many categories when I think of Medieval History compared to what I learned in early school. Alchemy was a not subject covered in a Catholic school in Canada. I can’t wait to download this book on my Kindle as I have others from this website.

My magic potion would be that people remember good memories.I have a 97 year old Mother with alzheimers and all she can talk about is good, not relevant but good.

A potion to get through the bad times by remembering the good!

An Elixir to dispel all Evil committed by Mankind

Politicus Terminus — a potion to prevent politicians from speaking ill of each other — especially during the U.S. presidential election cycle!