Thank you so much to Mickey Mayhew for sharing this chapter from his latest book House of Tudor – A grisly history with us today.

Thank you so much to Mickey Mayhew for sharing this chapter from his latest book House of Tudor – A grisly history with us today.

You can buy the book on Amazon UK at https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/1399011049/, Amazon.com at https://www.amazon.com/House-Tudor-History-Mickey-Mayhew/dp/1399011049/, or your usual bookstore.

Over to Mickey…

Anne Boleyn was executed on 19 May 1536, in the grounds of the Tower of London. This pivotal moment in history took place directly between the White Tower and the Waterloo Block, the latter being the location where the crown jewels are currently housed. She was most certainly not executed on the site of the glass memorial to those beheaded within the walls of the Tower, despite what the Beefeaters and several less well-informed books about Anne Boleyn might try to tell you. The actual, authentic spot of her execution isn’t marked, but if you station yourself directly between the White Tower and the Waterloo Block then you’re probably in pretty much the right position. If you visit the Tower of London on the date of her execution then you’re sure to see a great many of her fans coming to pay tribute, with flowers being left either on the aforementioned glass memorial or else in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula itself.

Rather than subject his second wife to the blunt humiliation and the often botched brutality of the axe – death by burning had also been mooted at one point during her trial – Henry VIII showed his disgraced queen a special ‘mercy’ by farming out the task to the famed swordsman of Calais. He would execute her in the more merciful French fashion, with a far sharper, more agile blade rather than a clumsy axe. Execution in the French fashion involved the prisoner kneeling rather than being sprawled out in an ungainly manner over a bloodstained block of wood, and the actual beheading itself was usually achieved in one swift stroke, rather than the ungainly hacking that sometimes accompanied an execution by axe. The swordsman had actually been sent for several days ahead of the outcome of Anne’s trial, so her ‘guilt’ was never in any doubt, although his delay in arriving – problems with horseshoes – meant that there were several unintentionally sadistic false-starts to Anne’s perceived final days. She mentally prepared herself for execution on several occasions only to be told that her imminent death had in fact been delayed because the swordsman, who might be swift when it came to lopping off heads, was in terms of timekeeping something of a slacker.

The swordsman of Calais’s special, ‘civilised’ method of execution also involved wearing a pair of soft-soled shoes as he scampered about the scaffold, so as not to alarm his victim. He would then distract his victims by calling out for his sword to his young boy assistant, who would be standing nearby. In fact, the sword would have been secreted elsewhere and the swordsman would pick it up as his victim turned their head to follow the sound of his request. At that precise moment, the swordsman would strike, the sinews on the neck of the victim being exposed to the maximum effect when the head was turned in such a way. Anne Boleyn was executed in exactly this manner, and her head was taken off so swiftly and so cleanly that many of the spectators for several seconds afterwards doubted what they had actually witnessed. Her lips were said to move for a further several minutes afterwards while her ladies were busily bundling her body into a nearby arrow-chest. No provision had been made for her disgraced corpse following her death, unbelievably, although whether this was an intentional slight or simply a gruesome oversight has never been adequately explained.

The graphic reality of execution by beheading was brought starkly to light by the famed historian Alison Weir, in the closing pages of her book The lady in the Tower. She cites the work of several French doctors whose experiments in the realm of death by decapitation concluded that almost every element of brain and body survives decapitation, however briefly, and that consciousness was indeed possible for the victim for several minutes afterwards. It is described by them as ‘a savage vivisection’: ‘In 1983, another medical study found that “no matter how efficient the method of execution, at least two to three seconds of intense pain cannot be avoided.”’ (Weir, 2009, p272). This leads to the dreadful thought that the victims of beheadings may have been aware and cognisant for a very brief time after their head was separated from the body. Indeed, when the head was held up by the executioner as proof of his success – as it often was – the victim may have still been ‘alive’ and thus staring out at the astonished crowd.

Before Anne Boleyn was subjected to this ‘savage vivisection’, she gave a short but eloquent speech to the assembled onlookers, telling them, among other things, that Henry VIII was the most kind and loving prince a wife and a kingdom could ever hope to have had. It simply wasn’t good form to bad-mouth one’s ex-husband on the scaffold when that ex-husband happened to be the king and when the fate of your daughter and also the rest of your family needed to be considered:

Good Christian people, I have not come here to preach a sermon; I have come here to die, for according to the law and by the law I am judged to die, and thereof I will speak nothing against it. I am come hither to accuse no man, nor to speak of that whereof I am accused and condemned to die, but I pray God save the King and send him long to reign over you, for a gentler nor a more merciful prince was there never, and to me he was ever a good, a gentle, and sovereign lord.

And if any person will meddle of my cause, I require them to judge the best. And thus I take my leave of the world and of you all, and I heartily desire you all to pray for me.

She was calm and composed throughout, but once her words were done and she was kneeling and awaiting the blindfold, she apparently kept glancing over her shoulder at the swordsman, her prayers half muttered. Quite possibly the blindfold was administered in order to prevent a post-decapitation view on the part of the condemned, or to save them from the curious faces of the crowd. It cannot have been to spare them the sight of the weapon itself, because the blow would always fall from behind or to the far side of their body. The pain would have been intense when the blow fell, but mercifully brief. She may have survived decapitation by several seconds or even by a minute or more, but equally, it may be that the shock of the blow killed her outright.

The swordsman of Calais was paid £23 6s 8d for his services. His real name is unknown, nor is it certain that he even originated from Calais. The identities of executioners were often kept a secret, for fear of retribution on the part of the families of their victims. Therefore, whatever happened to the actual sword that decapitated Anne Boleyn also remains a mystery. Were such a relic ever to be discovered then it would doubtless be considered quite priceless, though the provenance would be exceedingly difficult to prove. Whoever he was, the swordsman of Calais went to his grave without ever apparently disclosing how he felt about performing one of the most famous beheadings in human history. Even at the time, the execution of Anne Boleyn was quite astonishing – she was the first queen of England ever to suffer such a fate – and he can have been in little doubt that he had secured his own particular place in history for having performed such an act.

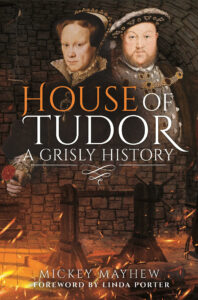

Blurb:

Gruesome but not gratuitous, this decidedly darker take on the Tudors, from 1485 to 1603, covers some forty-five ‘events’ from the Tudor reign, taking in everything from the death of Richard III to the botched execution of Mary Queen of Scots, and a whole host of horrors in between. Particular attention is paid to the various gruesome ways in which the Tudors dispatched their various villains and lawbreakers, from simple beheadings, to burnings and of course the dreaded hanging, drawing and quartering. Other chapters cover the various diseases prevalent during Tudor times, including the dreaded ‘Sweating Sickness’ – rather topical at the moment, unfortunately – as well as the cures for these sicknesses, some of which were considered worse than the actual disease itself. The day-to-day living conditions of the general populace are also examined, as well as various social taboos and the punishments that accompanied them, i.e. the stocks, as well as punishment by exile. Tudor England was not a nice place to live by 21st century standards, but the book will also serve to explain how it was still nevertheless a familiar home to our ancestors.

Gruesome but not gratuitous, this decidedly darker take on the Tudors, from 1485 to 1603, covers some forty-five ‘events’ from the Tudor reign, taking in everything from the death of Richard III to the botched execution of Mary Queen of Scots, and a whole host of horrors in between. Particular attention is paid to the various gruesome ways in which the Tudors dispatched their various villains and lawbreakers, from simple beheadings, to burnings and of course the dreaded hanging, drawing and quartering. Other chapters cover the various diseases prevalent during Tudor times, including the dreaded ‘Sweating Sickness’ – rather topical at the moment, unfortunately – as well as the cures for these sicknesses, some of which were considered worse than the actual disease itself. The day-to-day living conditions of the general populace are also examined, as well as various social taboos and the punishments that accompanied them, i.e. the stocks, as well as punishment by exile. Tudor England was not a nice place to live by 21st century standards, but the book will also serve to explain how it was still nevertheless a familiar home to our ancestors.

I’ve already ordered this book from Amazon in the US. Can’t wait for it to arrive! Claire, thanks so much for putting this excerpt up

The Tudor period really was a most ghastly age to live in