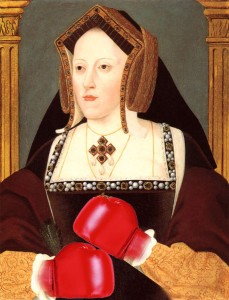

Today is the anniversary of Catherine of Aragon’s burial at Peterborough Abbey in 1536, so I just wanted to pose a question: “Was Catherine of Aragon right in fighting for her marriage and not accepting the annulment?” I’d love to hear your views on this so please do leave a comment. Allow me first to ramble…

Today is the anniversary of Catherine of Aragon’s burial at Peterborough Abbey in 1536, so I just wanted to pose a question: “Was Catherine of Aragon right in fighting for her marriage and not accepting the annulment?” I’d love to hear your views on this so please do leave a comment. Allow me first to ramble…

Catherine had experienced her last pregnancy in 1518 and it had ended in the birth of a stillborn daughter. Out of at least six pregnancies, Catherine had experienced four stillbirths, the birth of a son who had died at 52 days old and the birth of a surviving daughter, Mary. This catalogue of obstetric disasters had led her husband to believe that their marriage was wrong in the eyes of God and that he should never have married his brother’s widow, thereby breaking the law laid out in Leviticus: “And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it [is] an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.” A Hebrew scholar, Robert Wakefield, had told Henry VIII that the original Hebrew of that law in Leviticus was that the marriage would be without “sons”, rather than being “childless”, so Henry was convinced that he and Catherine had sinned and that the Pope’s dispensation for their marriage should never have been issued.1 Catherine did not agree. She argued that her marriage to Arthur had never been consummated and so there was no impediment to their marriage or anything wrong with it. Henry was not convinced, he felt that the tragedies of their lost children were proof.

It wasn’t as if annulments were out of the ordinary. In his TV series “Sex and the Church”, Diarmaid MacCulloch looked at the Church’s involvement in marriage and talked about the case of Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumberland, and his wife Maude in the 11th century. At the time, Church law was that no-one could marry within seven degrees of consanguinity. This made it difficult for the Normans in England because it meant that everyone they knew was out-of-bounds. Robert and Maude were Normans and were distant cousins affected by this law so they got a dispensation for their marriage. The marriage turned sour within two years due to Robert rebelling against the king and being branded a traitor. Maude wanted out of the marriage and so appealed to the Pope for an annulment, alleging that as they were cousins that their marriage was against Church law and so should be annulled. She was granted an annulment and then went on to apply for another dispensation to marry another of her cousins, Nigel d’Aubigny. Maude was unable to provide Nigel with an heir so he promptly argued for an annulment so that he could remarry. More recently, Louis XII had had his marriage to his first wife Joan annulled by the Pope so that he could marry Charles VIII’s widow, Anne of Brittany. So, Henry’s request for an annulment actually wasn’t that unusual and the Pope would have granted it if Catherine hadn’t opposed it.

The Pope was caught between a rock and a hard place, wanting to keep Henry VIII on side but also not wanting to upset Emperor Charles V, Catherine’s nephew, so when papal legate, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, arrived in England in 1528 ready to hear the case for the annulment, he met with Catherine and advised her to join a convent, something which would allow the marriage to be annulled easily. However, Catherine believed that she was Henry’s true wife and queen, and would not agree to taking the veil.

If only Catherine had accepted the annulment and gone to a convent, how history would have been different! Her daughter probably would not have been made illegitimate, the marriage having been made in good faith, and Mary would not have gone through the stress of having to defy her father, which included being threatened by members of her father’s council. Eustace Chapuys, the imperial ambassador, was so worried at one point about Mary’s safety that he advised her to submit to her father, reassuring her that “God looked more into the intentions than into the deeds of men.”2 The stress that Mary experienced seems to have had a major impact on her health and must have also had an impact on her as a person, her personality, the woman she would become later.

Of course, Henry’s quest for an annulment, due to Catherine’s opposition, led to him breaking with Rome and becoming the supreme head of the Church of England. This, in turn, led to the execution of those who would not sign the oath of supremacy (including the Carthusian monks, Bishop Fisher and Thomas More), reformers (those who Catherine viewed as heretics) influencing the king, and the dissolution of the monasteries. Catherine defying her husband had far-reaching consequences, something she could never have predicted. But Catherine was in an impossible situation. If she obeyed her husband then she would be compromising her faith. She had made vows to her husband before God and she was bound to her husband for life. As Garrett Mattingly puts it, “she was Henry’s wife; it would have been a sin to deny it”, but, “would it not also have been a sin to rebel against her husband?”3 Her conscience, her Christian soul, would not let her abandon her marriage because it put her soul, and that of her husband, into mortal peril.

Catherine’s decision, and what it led to, the consequences it had for her husband, her daughter and England as a whole, haunted Catherine in her final days. Eustace Chapuys, a man who had become a good friend to Catherine and Mary, visited Catherine in her final illness, reporting back to the Emperor:

“Out of the four days I staid at Kimbolton not one passed without my paying her an equally long visit, the whole of her commendations and charges being reduced to this: her personal concerns and will; the state of Your Majesty’s affairs abroad; complaints of her own misfortunes and those of the Princess, her daughter, as well as of the delay in the proposed remedy, which delay, she said, was the cause of infinite evil among all honest and worthy people of this country, of great damage to their persons and property, and of great danger to their souls.”

Chapuys assured her that what had happened in England “could in nowise be imputed to her” and was relieved that “This speech of mine made the Queen happy and contented, whereas formerly she had certain conscientious fears as to whether the evils and heresies of this country might not have been principally caused by the divorce affair.”4

In her final days, Catherine wrote a letter to Henry VIII. It no longer exists and it is not known for sure whether the transcripts which appear in later sources, like Nicholas Sander’s De Origine ac Progressu schismatis Anglicani and Nicholas Harpsfield’s A Treatise on the Pretended Divorce Between Henry VIII. and Catharine of Aragon is authentic.5 The words ring true, though, when we consider Chapuys’ reports of their conversations in those last days:

“My most dear lord, king and husband,

The hour of my death now drawing on, the tender love I owe you forceth me, my case being such, to commend myself to you, and to put you in remembrance with a few words of the health and safeguard of your soul which you ought to prefer before all worldly matters, and before the care and pampering of your body, for the which you have cast me into many calamities and yourself into many troubles. For my part I pardon you everything and I wish to devoutly pray to God that He will pardon you also. For the rest, I commend unto you our daughter Mary, beseeching you to be a good father unto her, as I have heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage portions, which is not much, they being but three. For all my other servants, I solicit the wages due to them, and a year or more, lest they be unprovided for. Lastly, I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things.”6

It is a moving letter. Even if it’s fictional, it does appear that Catherine never stopped loving Henry VIII and she always saw herself as his true wife and queen. To her dying day, she wanted to save Henry from himself.

Now this article doesn’t go into all the points, but I hope that it’s provoked you to think about Catherine. Could she have done anything differently? Should she have acted differently? Was she in an impossible situation? Could she have reconciled her faith and the annulment? Should she have put her country and her daughter before her feelings or would that have been putting her soul at peril? Was she disobedient and defiant? Should she have submitted to her husband and king? Please share what you think about this issue….

Notes and Sources

- Loades, David (2009) The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Amberley, p. 45, quoting BL Cotton MS Otho C X, f. 185. The Divorce Tracts of Henry VIII, eds. J. Surtz and V Murphy, xiii.

- Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5 Part 2: 1536-1538, 70.

- Mattingly, Garrett (1942) Catherine of Aragon, Jonathan Cape, p. 306.

- Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5 Part 2, 1536-1538, 3.

- Sander, Nicholas (1877) Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism (De Origine ac Progressu schismatis Anglicani), Burns and Oates, p. 131, originally published in 1586. Harpsfield, Nicholas (1878) A Treatise on the Pretended Divorce Between Henry VIII. and Catharine of Aragon, Camden Society, p. 199-200, written in the 16th century.

- This transcript from Mattingly, p. 308.