A big welcome to historian, author and novelist Toni Mount who is here celebrating the release of her eleventh Seb Foxley medieval murder mystery with a guest blog post. Congratulations, Toni! I love this series of books.

A big welcome to historian, author and novelist Toni Mount who is here celebrating the release of her eleventh Seb Foxley medieval murder mystery with a guest blog post. Congratulations, Toni! I love this series of books.

Over to Toni…

In my new Sebastian Foxley medieval murder mystery, The Colour of Bone, our artist-cum-sleuth spends time in St Paul’s Charnel House in London, making sketches of the bones of the dead, learning about the form of the human skeleton.

Charnel houses or ossuaries were small, sanctified store-rooms associated with medieval cemeteries. When new graves were dug, it wasn’t unusual to disturb the bones of a previous forgotten burial. Grave markers were rare and, if they were present at all, would likely be a simple little wooden cross just for the benefit of family and friends in mourning and would soon rot away. The disturbed bones were gathered up and taken to the charnel house to be kept safe for the resurrected soul to reclaim on Judgement Day. Oddly though, the bones of the individual skeleton weren’t stored together. The skull would be put with all the other disinterred skulls; the long bones with other long bones; pelvises, ribs and vertebrae in another collection. Often the smaller hand and foot bones weren’t saved at all but dispersed in the soil of the new grave. Perhaps they believed the soul would know its own bones or that God would reassemble them miraculously, if the soul was judged worthy of heaven.

Having Seb teaching himself anatomy in this way by spending time in St Paul’s Charnel House isn’t a ridiculous idea. His non-fiction contemporary in Italy, Leonardo da Vinci, did the same to improve his figure painting with a better understanding of the structures beneath the flesh. The difference is that Leonardo had the bodies of executed criminals to dissect; Seb has only disarticulated bones. Even so, he discovers that from the skulls and pelvic bones it may be possible to identify the remains as male or female. This idea is somewhat of a sideline to the main narrative of the novel but becomes of interest at the end. Seb believes that the skeleton in a tomb in St Helen’s Church is not that of the priory’s founder, William Goldsmith, but of a female. Is he correct?

The reader – and the author – don’t know for certain and even in the twenty-first century simple observation of skeletal remains can be misleading. We know that when the skeleton of King Richard III was first uncovered in a Leicester car park in 2012, the bones were thought likely to be female. The skeleton was described as ‘gracile’ – daintily built – and the skull didn’t have the definite brow ridges and heavier jaw which often denote an adult male. The other difference between male and female is seen in the pelvis where an adult female tends to have a wider pelvic arch to allow the passage of the baby’s head during childbirth; the male arch is usually narrower. Richard III’s pelvic arch was apparently somewhere in the middle; indeterminate. However, DNA tests proved that the lightly built skeleton was definitely male with a Y-chromosome: looks can be deceiving. So Seb could be mistaken if the long-dead William Goldsmith was as gracile as Richard III.

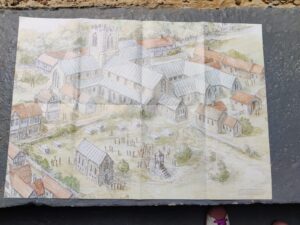

St Paul’s Charnel House is long since gone but London still has the remains of an ossuary associated with the cemetery of the Hospital of St Mary Spitalfields. This hospital was sited just to the north-east of the city, outside the walls on Bishopsgate Street. It was run by the monks of the Order of St Augustine until Henry VIII closed it down in 1538-39, along with all the other religious houses in England. The charnel house is a lucky survivor and I had a guided tour recently.

In 1539, the stored bones were unceremoniously shovelled out of the building and disposed of who knows where. The new Protestant religion saw no need to preserve such remains. Archaeologists may yet find them. The building was unusually fine for an ossuary although there are no indications of storage shelves ever being attached to the walls, as in similar structures on the Continent, so may be the bones were neatly piled in the corners where a few were discovered in the excavation of the site in 1999. While the other monastery buildings were demolished, the charnel house became a domestic dwelling for perhaps a century with the ossuary used as a kitchen and the chapel upstairs became the living quarters.

By the time of the Great Fire of London in 1666, the place was in ruins, lacking a roof and was therefore convenient for the disposal of charred rubble from the burned city. Filling it with rubble saved the building from collapsing in on itself, preserving it as the soil level rose around it and it was eventually paved over to become a thoroughfare. Late-twentieth-century building projects unearthed the site and the archaeologists moved in. Both the charnel house and the surrounding cemetery were excavated and the building preserved, although the cemetery is now beneath office blocks.

The archaeologists discovered the lower storey of the charnel house had always been partly underground with steps down from a door at ground level. Both documentary evidence listing the benefactors who paid for it and the architecture date its construction to 1320 but – there’s always a ‘but’ – there is an odd feature. The room was vaulted: seven vaults forming six bays, making it an unusually large charnel house. Six vaults were 14th-century pointed arches but the central vault was a Norman Romanesque semi-circular arch, exquisitely carved and the design painted in red, black and white. Obviously, this arch – dating to c.1120 – must have remained from a previous building on the same footprint about which nothing is known but it was beautiful and so well constructed that it was incorporated into the new build. Quite how the chamber was designed to meld the pointed arched ceiling either side into a round arch, unfortunately there isn’t enough architecture remaining to tell that tale. High on the south wall, i.e. at ground level outside, there was a row of small windows to light the room for the benefit of those stacking the bones, rather than the deceased occupants, and these made the room’s later use as a kitchen possible, one window being used as a flue for the cooking fire.

But why did St Mary’s Spital, as it was known, require a large new charnel house in 1320? This pre-dates the arrival of the terrible Black Death by almost thirty years. Archaeologists record deaths in cemeteries under three headings: attrition deaths are those which happen in a normal population at a fairly regular rate. Traumatic deaths are those caused in war or battle as a single event. The third is catastrophic death when there are so many bodies over a slightly longer period as would happen in a time of plague. So archaeologists excavating the surrounding cemetery were expecting to find the normal number of attrition deaths which had built up over the centuries and the bones needed to be set aside to make room for new graves. That wasn’t quite what they found.

Apart from single occupancy graves dotted around, they found mass graves with up to fifty bodies in each. Mass graves aren’t left open for long so the fifty must have died within a week or so of each other. Altogether, more than 10,000 bodies were found. This was catastrophic death on a huge scale but plague couldn’t be the cause. What was it?

Unlike plague which kills swiftly and leaves no trace on the bones, these skeletons showed signs of long-term malnutrition. Most likely, hundreds had died of starvation and thousands more of the associated problems and illnesses they no longer had the strength to fight off. And this fits the historical facts about the first quarter of the 14th century. The year 1300 saw the population of England and Europe at its maximum. Numbers would not be so high again until the 17th century. The 1200s had been a time of fair weather and good harvests across the world so the population had grown and reached the limits of food production possible with the farming techniques of the period. Then came disaster.

Crop failure after crop failure resulted from a sequence of cold winters and chilly wet summers when the sun hardly shone. Between 1315 and 1322 with the worst year being 1317, there was a devastating famine across Europe. Livestock had little grass to eat; hay rotted and animals died. Their meat couldn’t be salted to preserve it because salt manufacture was mostly done by evaporating sea water which requires sunshine and no rain. So meat also rotted. The seed corn that should have been planted for next year’s crop was eaten to ward of starvation. The terrible weather continued so by 1320, when the charnel house was built, the starving masses were coming to London – many from the farmlands of East Anglia – in search of food. Even the wealthy weren’t much better off: in times of famine, money couldn’t buy food if there was none to be had. So the human flood from East Anglia reached London, weak and ailing, and their last place of refuge on the road was St Mary’s Spital. Thousands got no farther and died there but at least they were given a Christian burial. Those who had dropped by the roadside on the journey would have been left to the kites, crows, foxes and rats to dispose of. This was a time of catastrophic death little noted in the records.

The change in climate was caused by the cataclysmic eruption of a volcano in SE Asia. The exact date isn’t known but scientists suggest it happened between 1275 and 1300. Clouds of ash and poisonous gases gradually spread throughout the atmosphere, affecting the whole globe for centuries to come in the ‘Little Ice Age’ and for decades at least the sun was shrouded. There is evidence in the Americas for famine devastating Inca culture and other native peoples from Canada to Chile. Volcanic ash from this period is found in ice cores in both Greenland and Antarctica so the entire planet was affected. In 1317, Europeans wouldn’t know of the cause nor how extensive the problem was beyond their own world but they certainly suffered the results.

No such worldwide catastrophe occurs in my new novel, The Colour of Bone, although the hard winters continued during the period in which it’s set: 1480. All the traumas are local and confined to far fewer victims. Will Seb unravel this new set of murder mysteries among the high born and the religious? And what of those bones of the benefactor?

Read The Colour of Bone to find out.

Book blurb – The Colour of Bone

It’s May 1480 in the City of London.

When workmen discover the body of a nun in a newly-opened tomb, Seb Foxley, a talented artist and bookseller is persuaded to assist in solving the mystery of her death when a member of the Duke of Gloucester’s household meets an untimely end. Evil is again abroad the crowded, grimy streets of medieval London and even in the grandest of royal mansions.

Some wicked rogue is setting fires in the city and no house is safe from the hungry flames. Will Seb and his loved ones come to grief when a man returns from the dead and Seb has to appear before the Lord Mayor?

Join our hero as he feasts with royalty yet struggles to save his own business and attempts to unravel this latest series of medieval mysteries.

Find the book on Amazon now – https://mybook.to/colour_of_bone

Toni Mount is a best-selling author of medieval non-fiction books. She is the creator of the Sebastian Foxley series of medieval murder mysteries and her work focuses on the ordinary lives of fascinating characters from history. She has a first class honours degree from the Open University and a Master degree by research from the University of Kent, however her first career was as a scientist which brings an added dimension to her writing. Her detailed knowledge of the medieval period helps her create believable characters and realistic settings based on years of detailed study.

Toni Mount is a best-selling author of medieval non-fiction books. She is the creator of the Sebastian Foxley series of medieval murder mysteries and her work focuses on the ordinary lives of fascinating characters from history. She has a first class honours degree from the Open University and a Master degree by research from the University of Kent, however her first career was as a scientist which brings an added dimension to her writing. Her detailed knowledge of the medieval period helps her create believable characters and realistic settings based on years of detailed study.

www.tonimount.com

Look out for Toni Mount’s other guest articles on her blog tour: