I’ve recently written about Anne Boleyn, her personal faith and her role in the Reformation, but let’s not forget her “partner in crime”, the man she bounced ideas off, the man she discussed theology and the new learning with, and the man who fell from grace when she did: George Boleyn, Lord Rochford.

At this point I’d like to introduce you to Clare Cherry who, in my eyes, is a bit of a George Boleyn expert. She comments on the site as “Louise”, so you don’t get her mixed up with me, and has a wealth of Tudor knowledge. She kindly agreed to write this George Boleyn article.

George Boleyn, Religion and the Reformation

In the early 1500’s the church meant the Catholic Church and its inherent rituals. There was no other religion, but there were those who actively pursued religious change, often at great personal risk. One of the most fervent reformists was George Boleyn, no doubt initially influenced by his father, Thomas Boleyn. It would be impossible to write about George Boleyn’s life without writing about his religious beliefs, which were an integral part of his character.

Until Henry VIII broke with the Church of Rome, England was a devoutly Roman Catholic country. Henry himself was fervently Catholic and, until his desire for a divorce led him to a break with Rome, he actively persecuted religious reformists. This led to the Pope giving him the title, ‘Defender of the Faith’, a title he was immensely proud of. Despite Henry’s active persecution of those who failed to conform to the orthodox Catholic faith, Thomas Boleyn favoured reform of the church, as did his youngest two children. It was their religious idealism which bred in zealous Catholics a hatred of them which continued long after their deaths, and which spawned many of the rumours, innuendos and slanders against them that persist to this day.

Reform amounted to a desire to rid the church of increasing greed and corruption, for the rites of the faith to be reformed, and for the word of God to be accessible to the masses. George and Anne Boleyn were not only devotees of this idealism; in time they came to embody it.

Henry’s views hardened towards Rome between late 1532 and 1535 as the Pope refused to bend to his will and grant a divorce, but in the late 1520’s and into the 1530’s reformist literature was still banned in England. George Boleyn’s regular trips abroad in the early 1530’s enabled him to obtain religious literature that was banned in England and across most of Europe. Any literature he brought back was read with interest not only by George but also by his sister Anne.

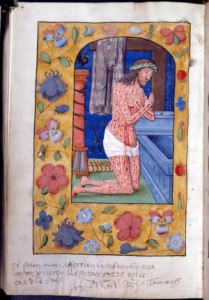

When Anne and George’s goods were confiscated after their deaths there were a large number of evangelical books written in French that had belonged to them. George turned two of them into magnificent presentation manuscripts for his sister. The manuscripts were based on works by Jacques Lefevre d’Etaples entitled, ‘Les Epistres et Evangiles des cinquante et deux sepmaines de I’an’ (The Epistles and Gospels for the Fifty-two Weeks of the Year) and ‘Book of Ecclesiastes’. These were cheap printed books that would have been hard to obtain in England in the early 1530’s, unless you happened to be the King’s future brother-in-law.

In both books the texts and readings were in French. The commentary stresses the need for a living faith in Christ rather than relying on the rituals and practices of the orthodox Catholic Church, which was precisely the ideology of Martin Luther, thereby codifying the reformist doctrine. They were also deeply concerned with making the scriptures available to the general public. The first to be transcribed was ‘Les Epistres et Evangiles’, with ‘L’Ecclesiaste’ being translated after Anne had become Queen. The Epistles is badly water damaged but is prefixed with a dedication, which was believed to be by George’s father-in-law. Recently, however, a passage prefacing the dedication reading, ‘moost lovyng and frynddely brother’ was discovered by means of ultraviolet light. This led historian James Carley to the inevitable conclusion that the author of the translation was actually George Boleyn himself. This is supported by the presence of a cipher on one of the pages that was probably designed by Holbein, and is clearly a cipher of George and Boleyn.

The dedicatory letter to his sister which George prefaced to “The Epistles and Gospels” reads as follows:

‘To the right honourable lady, the Lady Marchioness of Pembroke, her most loving and friendly brother sendeth greetings.

Our friendly dealings, with so divers and sundry benefits, besides the perpetual bond of blood, have so often bound me, Madam, inwardly to love you, that in every of them I must perforce become your debtor for want of power, but nothing of my good will. And were it not that by experience your gentleness is daily proved, your meek fashion often times put into use, I might well despair in myself, studying to acquit your deserts towards me, or embolden myself with so poor a thing to present to you. But, knowing these perfectly to reign in you with more, I have been so bold to send unto you, not jewels or gold, whereof you have plenty, not pearl or rich stones, whereof you have enough, but a rude translation of a well-willer, a goodly matter meanly handled, most humbly desiring you with favour to weigh the weakness of my dull wit, and patiently to pardon where any fault is, always considering that by your commandment I have adventured to do this, without the which it had not been in me to have performed it. But that hath had power to make me pass my wit, which like as in this I have been ready to fulfil, so in all other things at all times I shall be ready to obey, praying him on whom this book treats, to grant you many years to his pleasure and shortly to increase in heart’s ease with honour’1

The above dedication from George to his sister, in addition to exemplifying the strength of the Boleyns’ religious beliefs, also shows the depth of affection between Anne and George. In it he sets out beautifully expressed compliments to his obviously much loved sister. This highly intelligent young man incorporates in the dedication the type of self-deprecation that only the very clever risks voicing, in the knowledge that it will be received by a recipient who fully appreciates the false modesty! Be that as it may, George clearly demonstrates an anxiety for it to please his sister. He does, however, include the proviso that if there are faults, then she is to remember it was she who asked him for the translation in the first place. The dedication refers to Anne’s ‘meek fashion’ which she was not particularly renowned for, and says George is not giving her jewels etc because she has enough of them. It is possible to read, not only a dedication by a younger brother to his sister which is caring and affectionate, but one that is also written with a little jovial cheekiness. This dedication is the closest we come to getting a glimpse of the actual relationship between the two of them.

L’Ecclesiaste translation does not contain a dedicatory letter. It is probable that one did originally exist which has either been lost or deliberately removed. The lack of a dedication would make it hard to determine who translated it. However, it shares the individualised characteristics of ‘The Epistles and Gospels’ translation. As Carley points out both books represent a level of manuscript normally commissioned by royalty or the highest level of aristocracy. Only George Boleyn or someone of his calibre would have been able to afford to employ the same competent scribe and first class artists on two occasions.

Although George Boleyn was known and admired as a scholar even during his own lifetime, these are the only two translations that can definitely be attributed to him. However, in his scaffold speech he refers to being, ‘a setter forth of the word of God’, which suggests there were others which are now lost or which, like his poetry, are attributed to other people. Yet the translations we know George was responsible for prove that when it came to issues of religion, he was equally as active as Anne. Certainly in Anne’s own religious views and opinions, the presence of her brother is unavoidable. The two surviving manuscripts show that George was much more than just a reader of novelty religious literature as he has previously been accused of being. His evangelism was not a newfound trend that he discovered shortly before his death. He was an active participant much earlier than that, and from his youth identified himself as well as Anne with the new theological idealism. In matters of religion they were a team.

The translation George undertook for Anne emphasises the Lutheran doctrine of salvation being found only by faith in Jesus Christ. For Anne to have asked George for the translation, and for George to have personally undertaken this monumental task, confirms their commitment. It has been suggested that their interest was on a superficial level, more to do with being drawn to a trendy new idealism than genuine religious fervour. Their commitment is proved to be far greater than mere fashion. George spoke at length on the scaffold regarding his religious views and is unlikely to have spent the last minutes of his life doing so had he not been fully committed. The fact that George is responsible for these translations authenticates a passage in his scaffold speech uniquely recorded by a Calais soldier named Elis Gruffudd. Gruffudd’s original account of the speech is in Welsh, but the translation reads:

‘Truly so that the Word should be among the people of the realm I took upon myself great labour to urge the King to permit the printing of the Scriptures to go unimpeded among the commons of the realm in their own language. And truly to God I was one of those who did most to procure the matter to place the Word of God among the people because of the love and affection which I bare for the Gospel and the truth in Christ’s words’.2

There can be little doubt that the Boleyns used their positions at court, and the protection which derived from the favouritism of the King to promote their religious ideals. Sometime during 1528 Simon Fish, a religious controversialist, sent a religious pamphlet entitled, ‘A Supplication for the Beggars’ to Anne Boleyn. It consisted of religious propaganda emphasising the abuses of the ecclesiastics in order to urge the abolition of the monasteries. The pamphlet was nothing more than a religious rant, but among the complicated theological reformist arguments, this book was useful for its simplicity and brevity. George either noticed the pamphlet or was given it by Anne. According to Fish’s wife, ‘This book her brother seeing in her hand, took and read, and gave it to her again, willing her earnestly to give it to the king, which thing she did’ 3. When George had read it he obviously recognised its potential, by presenting to Henry a document which would be easily understood by him, and one which would appeal to Henry’s mercenary nature and egotism. As George well knew, as early as 1528 this document amounted to heresy, and only Anne could have brought it to Henry’s attention with a guarantee of impunity. As George foresaw, Henry was impressed with the pamphlet and had a personal meeting with Fish some two years later.

George’s influence in the religious changes which swept the country in the mid 1530’s has always been largely overlooked. But his translations for Anne and the incident with the supplication clearly demonstrates his influence over his sister and, through her, Henry, when it came to reform, and further authenticates the above passage in his scaffold speech. Anne may have been the mouth piece because of her influence over the love struck Henry, but right alongside her throughout was her brother. Henry was by no means a natural reformist, but if it suited his purpose he allowed himself to be easily influenced. Henry’s lust for Anne meant he was ripe for conversion provided reform meant getting what he wanted, and obviously the Boleyns had the intelligence to exploit their King’s shallowness.

George’s influence in the religious changes which swept the country in the mid 1530’s has always been largely overlooked. But his translations for Anne and the incident with the supplication clearly demonstrates his influence over his sister and, through her, Henry, when it came to reform, and further authenticates the above passage in his scaffold speech. Anne may have been the mouth piece because of her influence over the love struck Henry, but right alongside her throughout was her brother. Henry was by no means a natural reformist, but if it suited his purpose he allowed himself to be easily influenced. Henry’s lust for Anne meant he was ripe for conversion provided reform meant getting what he wanted, and obviously the Boleyns had the intelligence to exploit their King’s shallowness.

From his first introduction to court as an adult, George was particularly open in his support of religious reform. This, together with his intelligence, charm and linguistic skills had the effect of distinguishing him from the run of the mill young courtier, but it also turned many against him who continued to support the orthodox Catholic faith. It is easy to look back with hindsight and see that George Boleyn set himself up for a fall at a very early age. The Spanish ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, complained that Rochford insisted on entering into religious debate whenever he was being entertained by him 4. Yet, irrespective of what the likes of Chapuys believed, the Boleyns were not Protestant as we understand it. They sought reform of the Catholic religion, not a complete departure from it, and both of them died as Catholics. They obviously supported a break with Rome because that was essential in order for Anne to become Queen, but their passion for reform did not mean that they altered their basic religious beliefs, and for them, the break also meant that the reforms which they envisioned could be brought to fruition. They died as reformist Catholics, not as Protestants. George spoke passionately of his religious beliefs on the scaffold:

‘(Men do common and say that I have been a setter forth of the word of God)

I was a great reader and a mighty debater of the Word of God, and one of those who most favoured the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Wherefore, lest the Word of God should be slandered on my account, I now tell you all Sirs, that if I had, in very deed, kept his holy Word, even as I read and reasoned about it with all the strength of my wit, certain am I that I should not be in the piteous condition wherein I now stand. Truly and diligently did I read the Gospel of Jesus Christ, but I turned not to profit that which I did read; the which had I done, of a surety I had not fallen into such great errors. Wherefore I do beseech you all, for the love of our Lord God, that ye do at all seasons, hold by the truth, and speak it, and embrace it; for beyond all peradventure, better profiteth he who readeth not and yet doeth well, than he who readeth much and yet liveth in sin’. 5

That is one of the most poignant elements of the tragedy of 1536 and it is exemplified in an earlier part of George’s scaffold speech when he says in anguish that he is, ‘dying with more shame and dishonour than has ever been heard of before.’ Anne and George were deeply religious, and when Henry allowed them to be accused of incest, not only did he condone the siblings’ murders; he also allowed them to be morally ripped apart.

Notes

1 George Boleyn’s cipher and his dedication to Anne, MS 6561, fol. iv. MS 6561, fol. 2r. (British Library)

2 The speculation as to where the account originates from is from Carley, Illuminating the Book, p. 277 n. 43, Gruffudd’s chronicle, NLW, MS 3054D, part ii, fol. 511r. Likewise it is Carley who attributes L’Ecclesiaste to George, and his influence over Anne’s religious views and opinions. See Illuminating the Book, p. 272 and The Books of Henry VIII and his Wives, p. 131

3 Foxe, Acts and Monuments, vol iv, p. 657

4 Chapuys’ complaint regarding George’s Lutheran discussions, Calendar of State Papers (Spanish), 1536-38, p. 91, LP, x. 699

5 George’s scaffold speech, S. Bentley, Excerpta Historica, p.262-3 (1831)

Further Reading

- Article ‘Her moost lovyng and fryndely brother sendeth gretyng’ Anne Boleyn’s Manuscripts and Their Sources by James P Carley in Illuminating the Book, ed M P Brown and S McKendrick (1998)

- The Books of Henry VIII and His Wives by James P Carley