Following on from her recent and popular article “Being George Boleyn”, Clare Cherry examines the myths surrounding George Boleyn’s sexuality. Over to Clare…

One of the most asked questions about George Boleyn is with regards to his sexuality. What I regularly see time and again is the comment that there were rumours he was either homosexual or bisexual. The suggestion that George may have had same sex relationships has become so widespread that people are obviously led to believe that there must have been rumours during his lifetime or/and immediately following his death. Can I say once and for all that this was not the case.

We have no evidence whatsoever to suggest there were rumours relating to George Boleyn’s sexuality until the theory was put forward by historian Retha Warnicke1 in the 1980s. The suggestion of George’s sexuality stems solely from Warnicke’s thesis in which she also theorised that the cause of Anne’s fall was due to her miscarrying a deformed foetus in January 1536. There were no rumours of George’s sexuality during his lifetime or at the time of his death. None of the men charged alongside Anne were charged with buggery, which is a myth that has also come about in the last thirty years or so, and which is sadly repeated in some works of non-fiction as well as fiction. Therefore, it’s hardly surprising that people regularly take it as fact.

Firstly lets look at the reasoning behind Warnicke’s theory. She based it on four premises:-

1. A poem entitled ‘Metrical Visions’ by George Cavendish who had been the gentleman usher to Cardinal Wolsey.

2. George’s scaffold speech.

3. The fact that George lent/gave a book to Mark Smeaton which was a satire on marriage

4. The likelihood is that the marriage of Jane and George Boleyn was childless

If we take them one in turn, then the last two are easier to deal with. Firstly the fact that George and Jane’s marriage would appear to have been childless. To suggest that a childless marriage automatically means that the husband’s sexual preferences lead elsewhere is a theory which would have many twenty-first century husbands reaching for a shotgun! Childlessness is a sad situation even today with IVF treatment readily available. That Jane hated her husband because of his sexual leanings is also completely unfounded. We have no evidence to suggest their marriage was unhappy or that Jane hated him, let alone that she hated him because he preferred men.

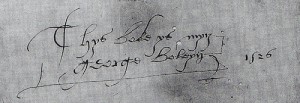

Then we have Warnicke’s suggestion that the fact George lent a satire on marriage to Mark Smeaton meant they were probably lovers. This is the sole piece of evidence she puts forward to support her theory and I find that rather a leap of imagination. George certainly owned the book because he wrote in it, ‘Thys boke ys myn, George Boleyn 1526’. Thomas Wyatt also wrote in it so clearly it did the rounds of a number of different courtiers who probably viewed it as a titillating bit of fun.

Cavendish’s poem and George’s scaffold speech are, to an extent, intermingled. Cavendish’s verses are about the men and women who were executed during the reign of Henry VIII. He writes as if from the mouths of the people who died. In George’s case Cavendish’s has him say:-

‘My life not chaste, my living besti*l

I forced widows, maiden I did deflower.

All was one to me, I spared none at all,

My appetite was all women to devour

My study was both day and hour,

My unlawful lechery how I might it fulfil,

Sparing no woman to have on her my will.’2

He goes on to say:-

‘Alas! To declare my life in every effect,

Shame restrains me the plains to confess,

Least the abomination would all the world infect:

It is so vile, so detestable in words to express,

For which by the law, condemned I am doubtless,’

Despite the fact that the first verse only refers to alleged womanising, Warnicke’s theory works on the premise that when Cavendish refers to George’s unlawful lechery and besti*lity he is actually covertly referring to homosexual activity. Again, to me that seems to be a massive leap of imagination. In any event, the words Cavendish uses are not solely used to describe George. In Cavendish’s other verses he uses the same phraseology. He has Thomas Culpepper warning his fellow courtiers of their besti*lity, and in his verses regarding Henry VIII he also talks of Henry’s unlawful lechery. Cavendish isn’t talking about homosexual activity, he is talking about adultery.

Warnicke also suggest that in the second verse referred to above Cavendish is suggesting that the crime George is saying he is too ashamed to confess is buggery. However, if you read the whole verse it says he is too ashamed to confess the crime for which he was condemned. He was condemned for incest with his sister, not buggery, and it is incest with his sister which he never confessed to, either in court or on the scaffold.

That leads me on to George’s scaffold speech. His scaffold speech was lengthy, but within it is the following section:-

‘And I beseech you all, in his holy name, to pray unto God for me, for I have deserved to die if I had twenty (or a thousand) lives, yea even to die with more shame and dishonour than hath ever been heard of before. For I am a wretched sinner, who has grievously and often time offended; nay in truth, I know not of any more perverse sinner than I have been up till now. Nevertheless, I mean not openly now to relate what my many sins may have been, since it were no pleasure for you hear them, nor yet me to rehearse, for God knoweth them all.’3

Despite the fact that in the sixteenth century it was considered an honourable death for the convicted man to accept death as deserved, Warnicke theorises that George is obviously covertly referring to homosexual activity. Once again, this is not obvious to me, and yet again I think it’s a massive leap of imagination to suggest so.

At the start of this article I said that Cavendish’s verses and George’s scaffold speech are, to an extent, intermingled. If you read this section of George’s speech, and then you read Cavendish’s verses, there is a direct correlation. There is a very good reason for that. In his verses, Cavendish is attempting to interpret George’s scaffold speech. Cavendish’s interpretation was that the sins George was referring to were adultery and womanising. In the twentieth century Warnicke reinterpreted Cavendish’s interpretation to suggest he was referring to buggery. On the Wikipedia page I added a piece indicating that I believe this creates a paradox. Two pieces of evidence are used to argue that George Boleyn committed buggery, and each one relies on the other for existence, thereby creating a circular argument; hence the paradox.

What Warnicke never explained is why, if rumours of George’s sexuality had been so prevalent at court that Cavendish knew about them, George was not charged with buggery and why no evidence of it exists. Why also would Cavendish have merely insinuated it when he had every reason to shout it from the rooftops, as did other Boleyn enemies such as Chapuys. Apparently Cavendish knew about it, yet it remained completely secret. To me that is simply not credible.

Warnicke’s theory as to George’s sexuality has been picked up by Alison Weir in ‘The Lady in the Tower’, but historians such as Ives, Loades, Starkey and Bernard dismiss it out of hand. If this theory had merely lived on the pages of two non-fiction books then it would probably not have gained a great deal of credence, and would have eventually been dismissed due to lack of evidence.

But then there was a book published entitled ‘The Other Boleyn Girl’ which had a huge impact and was extremely popular. In it the author chose to incorporate Warnicke’s theory and fictionalised George having an affair with the courtier, Francis Weston. The book is fiction, but irrespective of that the seed was sown for the majority of historical fiction which followed, including the highly successful programme, ‘The Tudors’, in which George was also portrayed as a wife abuser and rapist. Because the theory has been repeated time and time again in fiction it has gained acceptibility and credibility by repetition, because surely if something is repeated often enough then there must be some substance to it? So the theory becomes treated as fact without really knowing the truth of what that theory was based on.

Back to Claire (Ridgway)

Thanks, Clare!

I agree whole-heartedly with Clare’s comments here on the whole homosexual/bisexual theory and would just like to add the following points:-

- There is no evidence that Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, Sir William Brereton or Mark Smeaton were what Warnicke terms as “libertines” either.

- The only evidence for the deformed foetus is Nicholas Sander writing in 1585. He wrote that Anne miscarried “a shapeless mass of flesh”,4 but then he also wrote that she had six fingers, a wen and a protruding tooth! He was six years old in 1536 and was a Catholic in exile during Elizabeth I’s reign so wanted to blacken the names of Elizabeth and Anne. Chronicler Charles Wriothesley and Anne’s enemy, Eustace Chapuys, write of Anne miscarrying a male child of around 15 weeks in gestation.

- The satire that Warnicke mentions George lending Mark Smeaton was a translation by Jean Lefèvre of Mathieu of Boulogne’s 13th century satirical poem “Liber lamentationum Matheoluli”, or “The Lamentations of Matheolus”.The poem is an attack on women written by a man betrayed by one. In the poem, Mathieu likens women to basilisks – refers to “a chimaera with horns and a tail” and “ the mother of all calamities”, and writes of how “all evil and all madness stem from her”. What Warnicke does not mention is that this poem was widely circulated amongst scholars in Europe and that it “quickly became one of the most seminal examples of medieval antifeminist and antimatrimonial discourse”.5 It has been suggested that Chaucer6 knew of this poem, and drew on it heavily for “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue”, and that Christine de Pizan was inspired into refuting it in her “Cité de Dames”.7 It was probably something that was being discussed by George, Wyatt, Smeaton and other members of the Boleyn circle, and is not evidence of a love affair between George and Smeaton.

It is time to put this myth to bed, as it were, and to remember George for his accomplishments instead.

Notes and Sources

- The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII, Retha Warnicke, p214-216

- Metrical Visions, p22, in The Life of Cardinal Wolsey, George Cavendish, Volume II

- Gruffudd’s Chronicle, NLW, MS 3054D, part ii, fol. 511r

- “The Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism”, Nicholas Sander, p132

- Gender, Rhetoric, and Print Culture in French Renaissance Writing, Floyd Gray, p17 and 18

- Matheolus, Chaucer, and the Wife of Bath, Zacharias P. Thundy, in Chaucerian Problems and Perspectives

- Chaucer’s Legendary Good Women, Florence Percival, p 106

Considering the very spirited defense Claire and Clare have given of both Anne and George, could anyone imagine how thoroughly Henry would have panicked had both Claires been present as attorneys for the defense?

“Drat. Now I’ll NEVER get rid of Anne and the Boleyn faction! Not with those two amazons on the defense team!”

Miladyblue, I enjoyed your comment! very funny 🙂

I think Henry and Cromwell would have been very busy, creating new laws and imagining charges to discredit ‘our’ Lawyers! We might to go and visit them in the Tower for challenging the Crown 🙂

miladyblue,your to funny!!As I said I don’t think they were aloud defense,and the Claire/Clare would most likley ending up much like Anne.Take a look at that snake Cromwell ,he was lawyer to the King and he lost his head.here here to the axeman that wacked his head off!! Regard Baroness

Great article! I’m happy that myths about the Boleyn family are fading away. I would like to ask one thing about Jane Rochford – I don’t believe she gave testimony against George, but was she present at his trial? I would be very grateful for answer.

Thank you Clare and Clare! can we now send this to Phillipa and Alison? Don’t get me wrong I like them both as writers, BUT to embroider on the truth and take such giants leaps of imagination and publish them is irresponsible. They and Nicholas Sander are in the ‘Calumny Club’. PG is a fiction writer, I can cut her some slack (although she now lables herself ‘historian’, but Alison Weir!? what happened to her??? while I respect their imagination exercises (contortions?) their ‘proof’ for their OPINION is such a speck. I cannot respect their decision to allow this rubish to be published. It is sad that in order to sell books their publisher advices such nonsense, I understand it is their jobs, but the writer has to have a backbone to protect their reputation and integrity. Clearly, they did not. It is a sad day when they blacken the reputation of a victim to put their name up and in front of the public. They have to debase their credentials by putting out such unfounded ‘truths’ Unfortunately, the public believes it ‘because it said so in the book’… It’s like the ‘Da Vinci Code’ all over!. And where did they find these books? in the FICTION section of the bookstore!! I wonder if the public will be interested in fiinding the truth; but, that will be too much work! ok, done ranting! thank you. EXCELLENT article. C&C you are top notch. (apologies for the bad grammar, I’m writing in a heated rush of disgust about the lies being spread about our beloved Boleyn siblings!)

Well said Nanboleyn. Sadly I don’t think that sending this article to the two ladies ine question would make a difference. They have made their minds up about what happened and therefore feel totally justified in spitefully gloating about the deaths of people who they never knew but feel entitled to judge morally.

George said he was a sinner at his execution for this simple reason that ,as it says in the Communion service, “All have sinned and fallen short of the Glory of the Lord”. There is no evidence that he was gay, a wh*re-master and anything else.

Excellent article, I couldn’t agree more. Again, it just shows you the danger of historians who try to fit the evidence to their own theories, and ignore every other piece of evidence which contradicts it.

Interestingly, I recently corresponded with Retha Warnicke, and she stated that she has released a new book which deals with Tudor women, in particular Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, and she informed me that she has found new evidence which conclusively proves Anne Boleyn was born in 1507 and was the elder daughter of Thomas Boleyn. It may be fascinating to see if the deformed foetus/homosexuality theories are picked up by her at all in this work.

I doubt that Anne could have been born in 1507 if she was the elder daughter!! I would like to see Warnicke’s evidence, but doubt it exists.

Having read all the things we know, the 1501 birthdate seems more probable and also the fact that Mary was the oldest, as her grandson claimed Thomas Boleyn’s title, being the descendant of Thomas’ first-born.

Poor George. I have to believe that if he was a homosexual then it would have been mentioned in the charges against him. How could those against the Boleyn’s pass up a buggery charge? Thankfully the two Claire’s are doing their best to clear George’s name. Also, I’m so glad you came to his defense on his childless marriage – maybe they just had trouble getting pregnant!

Great article!

What a great idea, miladyblue…Claire, attorney for the historically persecuted. Although Henry VIII had a long advantage in demonizing the Boleyns, he has now met his match.

Jeane Westin, The Spymaster’s Daughter, Penguin/NAL, August, 2012

We’d have the advantage too because Clare is a lawyer and I just don’t stop talking!

Claire,Clare you both would have made excellent defense for the doomed Queen’s I speak of all that Henry rid himself of, however i don’t think you and Clare would have your heads either,these poor soul’s. Where they even aloud to have a defense at trail??

I agree that both Claires would have made excellent defense attorneys … and Henry would have beheaded the pair of them (Thomas More was a lawyer, also). Tudor trials did not allow for the rights that we currently take for granted: notice of the charges, the right to call witnesses in your defense or to cross-examine the witnesses against you. However, there was some opportunity for argument, at least … IIRC,someone said that George did such a good job that he might have been acquitted … if he hadn’t read aloud a note asking him about Anne’s alleged comments concerning Henry’s “performance”

I must say, between Clare and Claire, I wouldn’t have nothing else to say, but for a few of the comments above. They are SUPERIOR! I looked again and again at the lines in botht he poem and George’s scaffold speech, and have to say, they have it down pat. I also agree with Fiz in that George was innocent, and his scaffold speech sound more to me like he is confessing, and that, “All have sinned and come short of the Glory of God.” I seem him confessing to this most of all. He, as Anne, did not admit to the crimes for which the law had judged them, or that they wished anyone anything except for a showing of his and Anne’s true nobility of blood by descent from Edward I. They died with the dignity only true nobility can do. Catherine Howard, yes, was Anne’s cousin on from Anne’s mother being sister to Catherines father, but the Boleyn noble blood goes back so much farther. Even Thomos Boleyn returned to court and gained favor again in 1539. That is not long.

I most certainly agree with NanBoleyn about Weir (I won’t mention Gregory except that her last book of which I know [and I am probably out of touch now] claiming to be a different kind of historian in the book with two archeologists was not well recieved – as of now I will be a gentleman and not even try to reach her low level as I can’t). Weir, and this has been is something on which has been commented on another site claims she cannot annotate her sources as, let’s say, Eric Ive’s does, as her publisher won’t let her. I commented on this one when I read, I believe, Weir said in an interview. The comment included that if that were the case then why woulnd’t she and/or her agent find another publisher (which wouldn’t be that hard as Weir is a selling name with regard to her area (at least she mostly keeps it their) or that her agent’s fee is too high to do that with another publisher, Weir is bound by contract right now or what ever. The fact that she doesn’t in all this time says everything of which I will comment. She, in my judgement (anyone can have an opinion, but a judgement is based on the the whole paragraph leading to this statemet – that’s of course, not in legal terms, but in historical research terms) has nothing to offer.

George as Clare and Claire have estabilshed (and thank you Claire for mentioning Chapuys!) that they have put this to bed. Period…the end…curtain. Nowadays, who would really care, unless they have doubts abour themselves or bring other things into the world that do not pertain. It didn’t work for Henry VIII when he applied for a dispensation as a verse in Leviticus did from Clement VII (a bastard, and uncle to the Holy Roman Emperor, KIng of Spain, grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella, “The Catholic Kings,” and nephew to Catherine of Aragon who had ransacked Rome (which ended up lending itself to Catherine de Medici’s rise [another subject for another time and/or forum] and controlled the Pope at that time) did in the 15020’s and early 1530’s until Henry broke with Rome and married Anne Boleyn, Queen of England, mother of Elizabeth I, and one person I will defend as long as I’m alive. Thank you! WilesWales

One other thought, and I’m glad I remembered it! As I was reading down the comments earlier, please, please never doubt Claire on her documentation, or her sources. I am referring to the correction on the poem. Claire has her areas of expertise, and I’m sure that this was not the first time that she ever saw or read this poem! I know this from the way she answered it, and above all, she knows her dates, and poetical metrical devices! Clare is a J.D. and that is another specialty outside of those of us who had to, in graduate school write a disseration or thesis (I had to both) on a particular thing, never before studied, write it, prove it, and draw a conclusion (and that’s short for the whole process), and it bring our undergraduate skills into play when we use certain things such as mentioned previously into play, and literature in our majors is almost always used to make a point, or use in the annotations and bilbiographies of what will now always be copyrighted, and be a part of the permanent collection of the United States Library of Congress. I don’t know about Britain, but I’m hope it does give the expert the same respect it deserves. Thank you, WilesWales

BRAVO!

I don’t give much credence to these rumours either. I truly believe there would have been at least “whispers” before his death. Why not use something like this against him at the height of his power? There are always those that wish ill and they would have made use of knowledge like this in the blink of an eye. Don’t you think?

Anything to trash the Boleyns and sell books. Tut, tut, tut.

How do we know the exact words both Anne and George used in their execution speeches?. I don’t think there was a tape recorder there and who could write fast enough to get it all down? Someone memorized the whole speeches? I don’t think so.

Great article as always.

I asked Claire that same Qs/As and he was not bisexual,it did seem that way in the Tudor’s with Smeaton aswell,so what if he was there were alot of gay’s back throuh out History, Regards Baroness Von Reis

Thank you for the article Clare and Claire. The damage done to Anne and George in their time was meant to ruin their names throughout history. Thanks to Clare and Claire that is being remedied. There is nothing like the truth!

Great job ladies! I wholeheartedly agree. I have a couple of Retha’s books, but haven’t had the heart to actually pick them up and read them for this reason. I would definitely like to know her difinitive proof for Anne being born in 1507 as the eldest. I thought this had mostly been proved to have been impossible? LOL Aren’t most historians accepting the 1501 or so birthdate?

“this is my book” from George to Anne, for he found HIS book in her room in a stack that belonged to HER. Dear George took it back, and was careful to inscribe there these famous words. There, Anne! Ask permission first! Lol

Great article both cs I agree that as prominateas George was there would have. Been gossip at court. Thanks

i think it’s shameful when non-fiction authors take liberties with facts. Historical fiction writers, however, by virtue of the moniker ‘fiction’ can make what they will of facts. in that instance the onus is on the reader to separate fact from fiction. for me, researching the reality- after reading a fictional book- is part if the fun.

Great article! Jane Boleyn seems likely to have been a somewhat jealous, peevish and vindictive- ample reason,perhaps, for George to have shunned relations with her- desite dynastic ambitions.

Once again, great articles by you both.

I for one would be very interested to hear what Retha Warnicke thinks on your arguments. Perhaps she could be invited to add her argument.

I’m sorry that I have to take issue with one little statement. You state,

“It has been suggested that Chaucer knew of this poem, and drew on it heavily for “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue”,”

This would be impossible. Chaucer died on 25 October 1400; George Cavendish.. wasn’t born until 1494.

Hi Lady Domino,

I was referring to the satirical poem written by Mathieu of Boulogne in the 13th century, the one which was passed around by George, Mark and Wyatt, not Cavendish’s Metrical Visions.

Thanks for your comment!

I now look forward to checking my e mail, as I love all the info you share. I also enjoy the intelligent and informed conversation on each topic. It’s so nice to have a community to discuss Henry/Anne and that dramatic , engaging time in history. Thanks so much for being there!

I have to admit, to those who have queried, I personally find the 1507 birthdate unlikely. My problem is the fact that a six-year old girl was supposedly made maid-of-honour to Princess Mary Tudor, and then retained while her other English attendants, including her “governess” Lady Guildford, were sent home. Warnicke claims Anne was brought up in the royal nursery with the other French royal children – why would she have been? Anne was not even a landed heiress, never mind royal. I find it hard to believe she would have been afforded such an opportunity. Although, perhaps, it’s difficult to see Anne only being courted by the King aged 26, and only married at 32/33, and dying at 35/36, I find it impossible to believe she was 6 years old at being a maid of honour, and then returned aged just 15. For this reason, as well as the fact that the Emperor wrote that a maid of honour was usually 13 or 14, I would say Anne was born c1500-1. Her letter to her father in 1514 is also clearly in the hand of an intelligent teenager.

Even harder to comprehend is Warnicke’s argument that Mary Boleyn was younger, and born in 1508. Warnicke claims Mary was born not before April 1508 – yet if she was so, she would have been aged 11 years old in 1520 when she married, as she married in February. This would have been illegal. So Warnicke undermines her own argument. The 1508 date is impossible, too. Mary was sent abroad 1514-1519, again, why would a 6 year old have been sent abroad, and returned just 11? I would say that Mary was born in 1499 or 1500, and was older. Even if she was younger than Anne – which seems highly unlikely – I would say she was born at the latest in 1501.

However, I do agree with Warnicke that George was born around 1503.

I agree with you, Conor. I personally don’t find it hard to believe that Henry fell in love with Anne when she was 26.. Jane Seymour was about the same age when he first noticed her.

Just as I have never believed that any of the men executed for “adultry”with Anne did so, I never believed George was homosexual or bi…if he was why would he have relations with his sister? This was what he was convicted of!. While most marriages were arranged without love…there is no proof George did not have relations with his wife or disliked her . Just as there is no proof he slept with his sister…Henry wanted to be rid of Anne an agreed with anything to accomplish that end,,i have always been surprised at that considering his ego, I am surprised he acted the “cuckhold’. When men/women go to die, they always have some “sins” to confess, and how you say it should not be miscontrued. As everyone has stated, the enemies of Anne never refeerred to any of this, just “future” historians”

Yes, Claire/Claire you would have met the same fate for your on spot defense of both Anne and George. Too bad for the sake of the almighty $ so many authors miscontrue or misrepresent history. Thank heavens for this blog.

That’s a good point. Also in Tudor society many of the ‘sins’ that people confessed to before their executions would have really been no big deal to our modern culture. Few people today for instance would consider that sex between two people who are unmarried is a mortal sin. But for George it would have been something that he would have been sure to confess before he died because it was considered to be so serious. Also I think that those people who say George was homosexual seem to have a very unpleasant attitude towards gay people. This is especially true in fiction where his supposed prefence for men is treated in the same light as the equally absurd allegations of incest and rape.

Great article, I can’t wait for the anniversary of Anne’s execution article!! I know you have new interesting things to write about.

I just finished Henry VIII and was pleasantly surprised on how good it was. I have a list of books you have reccomended and I’m slowly getting through them.

It would be great if someone does write a book on George Boleyn and all these rumors and speculation theories.

Warnicke and Gregory are authors and I understand that they would want to sell a book. However, Warnicke does need some help with her theories. As stated in other comments she does undermine her own evidence. I think Warnicke, Weir, and Gregory need to take a History class from Claire before they start proclaiming themselves as historians and all they have is inconclusive evidence and heresay.

I think these questions about George’s life, (and anyone elses life through history that little is known about,) they seem to become fair game for people to ‘make it up’ to fill in the gaps, or they take the smallest of detail and turn it into something ‘juicey’, its quite unfair really, and mis-leading.

You won’t believe how relieved I was to finally read something to this effect! I was so, so distressed when that despicable novel, ‘The Other Boleyn Girl’, was released (I was working at a bookstore at the time; even more troubling, watching everybody lapping up the lies) and have been resolutely trying to convince people of its falsity (on a one-by-one basis) ever since.

Thank goodness there are other people with brains, respect and basic common courtesy for the long-deceased innocents of our collective past. Slander is not okay by modern standards, and I have always struggled with the creative licence so-called ‘historical novelists’ exert while producing such publications.

Bravo!

I completely agree that there’s no evidence that George was bi or gay – however, I don’t see why writing him as such in fiction ON ITS OWN is insulting. Historical fiction always has characterizations that are inaccurate in some way or another because in fiction, you are trying to tell the best story.

Now, obviously, Philippa Gregory and ‘The Tudors’ handled it very badly, since George’s characterization (particularly in ‘The Tudors’, I found him more sympathetic in TOBG) was negative overall. But I feel like it’s something that could be included by an author who made it clear that it was a fictional embellishment.

I’m just getting the impression here that saying George was gay or bi is blackening his name in itself – even if we find evidence tomorrow that proves he was (which we won’t, but I’m trying to make a point), that shouldn’t blacken his name to anyone in the present day. I think it’s an interesting idea to consider in fiction, just like various other myths that are unlikely to be true – such as the handful of books about supposed children of Elizabeth. I’ve only read one, ‘The Queen’s Bastard’ by Robin Maxwell, and she makes it clear in an author’s note that there is no evidence for this, although she also relays where the ‘Arthur Dudley’ story came from.

An author who uses this myth about George Boleyn to enhance their story, but makes it clear that’s what they’re doing, can do that in my view. However, very good article in terms of refuting the idea that this is ‘fact’ – I blame Gregory for making people think that, since I would hope most people know ‘The Tudors’ plays fast and loose with the truth. But Gregory’s insistence that she writes fact doesn’t do any Tudor personage any favors.

I don’t think it’s blackening his name in itself, although Gregory states that her work is based on fact, it is what comes with it: unhappy marriage, jealous wife who betrays him, wife beating, incest, rape… you name it. He never seems to be just gay or bi-sexual. What we have to remember, as well, is that homosexuality was a sin and a crime in those days. It was seen as completely deviant behaviour.

A very good overhaul of he arguments for and against the sexual preference of George Boleyn and that it was suggested by Warnicke in her book several years ago, I have to confess it is a long time sine I read this but I am not surprised as she does have some different views on the whole Anne Boleyn saga. There is one indication that George may have been gay and that is the fact that he bemoans his sexual life on the scaffold as sinful. Gay relationships did not have the positive press in Tudor England that they must have today.

I must also confess that until I read the above I did not really give were the idea on behalf of George Boleyn came from; I just thought it was the Tudor’s being the Tudor’s and let’s face it; these days unless you have a bit of everything in a modern drama, gay sex, black couples, everyone sleeping with everyone and everything, men from outer space, alien beings, (I know, I am getting out of hand, but you know what I mean) every kind of group on the edge of society, then it does not get aired. The Tudors had a gay relationship in just about every series; so it is not surprising that they had one with George and Mark. The main problem that I have George having one with Mark Smeaton is that he would have gone for someone more of his own social standing. While Mark was a good musician on the make and would have access to the King and Queen and patronage from them; it is not likely that they would have sex with someone of that low a status. But, it is of course possible that George was gay; his marriage was not the most successful in the world as it was a business contract, but well, who knows what people were; we simply do not have the evidence either way.

You say ‘the fact that he bemoans his’….and then there’s a gap. I wondered what you intended to say?

Yes it is possible George was gay. After all anything’s possible, but it’s not a very good argument to base a theory on. It’s like saying Anne was a lesbian just because it’s a possibility that she was!

I didn’t base any theory on anything and I completed my sentence if you read it properly. I said the only evidence people used was his last words. Its not my theory, its that of people like Philippa Gregory who writes utter rubbish and other dramatic portraits who believe that Professor Warnicke made this argument in her work. She didn’t, she believed that was the case back in 1536 and that the morality of the Conservative party at Court was used to target men who had poor reputations. In fact only one or two had poor reputations with women and the others were actually targeted because they were standing in Cromwell’s way, were always in the company of the Queen so a reasonable case could be made against them or fell into the trap accidentally. As I said, they may well have been gay or not, but there isn’t any evidence to support these theories so why make such an argument just for cheap entertainment?

With reference to the paradox you mention, have you never thought a charge of homosexuality could call into question the charge of incest? As surely that is something the prosecution would definately seek to avoid? This article is an interesting read but I find it flawed in that you base all your arguments on what you believe, I.e I believe this is a stretch of imagination, history is a muddied field and so sources must be employed to prove a point, and any historian worth their salt both amateur or otherwise should try thier best to see both sides of the coin and proceed from there, I find here no real weighing of sources just a vehement dismissing of established historians work as it does not meet with your personal view point, and history should always be viewed objectivley. As for being a formidable match in a Tudor court room against the kind, I do agree with other commenters , your soul belief in your personal suit travels in a very similar vien to the prosecution of the day! George would have grown very grey in the tower!

I don’t think that Clare is dismissing “established historians work” because, in fact, Retha Warnicke and Alison Weir, are the only historians that give this claim any credence. None of George’s contemporaries mentioned him being homosexual and the majority of historians today don’t even mention it, never mind believe it. Retha Warnicke bases her opinion on George and Smeaton sharing a book, yet Thomas Wyatt also borrowed that book, and the words “unlawful lechery” which were also used by Cavendish to describe Henry VIII’s behaviour. Is anyone arguing that Wyatt or Henry VIII were homsexual? No, therefore the arguments do not make sense.

Whilst it is true that there is no evidence to suggest that George Boleyn was bisexual(or homosexual), we DO know that Mark Smeaton suddenly became a young Man of means; he wore the finest clothes and owned the best horses that money could buy. What were the wages of a lute player at King Henry’s court? If the wages were low, then perhaps George Boleyn was showering Mark with expensive gifts; Why? was mark’s music THAT good? was Anne giving these costly gifts to Smeaton? The English aristocracy are not known for their generosity, either today or back in Tudor England. To receive such beautiful and expensive gifts, Mark MUST have been doing a lot more than simply performing well with his lute! what we often forget when discussing characters from history is that they were real flesh and blood people, and like all people, they were neither black or white but shades of grey. And the English aristocray have always lived by their own rules; indeed Homosexuality(or bisexuality) is so rampant among that class that it is almost abnormal if you haven’t taken a walk on the wild side! I guess we will never know what really went on with Smeaton and George and Anne Boleyn; but it IS fascinating!

Mark was actually a favourite of the King. I talk about this in my book:

“The Privy Purse Expenses of November 1529 to December 1532 show frequent mentions of “marke”. In the introduction, the editor explains that it is clear that Smeaton was “wholly supported and clothed” by Henry VIII. There are many mentions of payments for “shert”s and “hosen”. His rise in favour is evident from the increase in his rewards during the period, from “xx s”i (20 shillings) in December 1530 to “iii li. vi s. viii d.”ii(£3 6 shillings and 8 pence) in October 1532. The increase in payments for clothing would also indicate this rise in favour.”

So perhaps Henry VIII was keen on Mark 😉

As for homosexuality being rampant, it was actually seen as a mortal sin in those times and if the men had been homosexual then it could have been another way of bringing them down. They were not charged with “buggery”, as it was termed then and they surely would have if there were rumours of inappropriate relationships. Wouldn’t Smeaton have confessed to that? I just don’t see there being any evidence for any of the men being homosexual, sorry.

my question is ,how and where would you find evidence that ,george boleyn or anyone else from that time was gay ,bisexual or whatever,and just because theres no evidence of it ,does not mean that george was not any of above mentioned ,and why does most people on this site have a serious problem accepting the fact that george could have been gay ,bisexual or whatever ,i know it was a sin back then and not spoken about but it existed and there should not be a problem in todays thinking on this.

I certainly don’t have any problem with George being gay or bi-sexual but I do have a problem with a theory being plucked from thin air and now being so popular that it is taken as fact. There was no mention of it at the time and it only dates back to the work of Retha Warnicke in recent times. It would be like me writing that Anne Boleyn was gay or bi-sexual, there is no evidence of that either and theories that make no sense should be challenged, just as we challenge the witchcraft idea.

homosexuality would not have been mentioned at all in tudor times so there would be no evidence of it ie written down ,far too dangerous for all involved ,what iif the nightly festivities in anne chamber had got out of hand with all involved ie all the men she was friends fron her younger days and several of her ladies in waiting ,who knows what could have happened ,anne was possibly being ignored by henry by this stage as he was off with jane somewhere and anne was used to being the center of attention and she did get this adoration and courtly love thrown in as well from the men in her circle all sorts of “games” would be played until as i said got a bit too much for maybe one or two of the ladies ,this could have been gossiped about and reported back to henry .if any of the men in question had been engaging in homosexuality ,and had this knowledge come to light it would have been well hidden because if known anne case of adultry would not have stuck at all ,i mean she cant commit adultry with homosexuals but i believe something happened to start the gossiping and talk and still not to bash anne but why was she spending so much time with you might class as her “college buddies”should she not have established a more varied group of people in her life as she was a queen and maybe acted accordingly as a queen she may have got on with her brother very well ,i get on with my brother very well but i dont discuss my marriage with him ,ie anne discussing henry with george ,i think theres a lot of information been lost a long the way about what really happened.

Homosexuality was mentioned in the Tudor court. It wasn’t called homosexuality, it was called buggery or sodomy, but it was referred to. In fact an Act of 1534 was passed making it illegal, and men were put to death under the Act.

As for what could have happened in Anne’s chambers, there’s no evidence for what you say. We can’t make something up because it ‘could’ have happened. Perhaps Anne had sex with her ladies-in-waiting for all we know, but there’s no evidence and there were no rumours or gossip suggesting it. That’s the point. There were no rumours or gossip about George being gay either. It only came about due to a theory which had no evidence to back it up.

We can’t base a theory simply on what ‘could’ have happened. That’s ridiculous.

Yes, poor old Walter Hungford, Baron Hungerford, was charged with buggery and beheaded in 1540.

It was mentioned in a number of ways, tracts against it, preaching, the teaching of the Church, in poems and lude verses, in the above law, in similar laws in Italy where it was illegal long before Tudor times, it was also shown in illustrations in sexual manuals in the Middle Ages, which while it was condemned, still recognised its existence. People were given penances and punishment for all kinds of forbidden sexual practices outside of marriage, one look at Church Court records shows that people followed their hearts just as they do now, regardless of it being right or wrong. The Buggery Act 1534 could easily have been used against those accused with Anne had they simply been a way to get rid of a group of unsavoury men, but they were not and that for me backs up the argument that their sexuality had nothing to do with their fall, it was more personal and dangerous than that. The majority of historians don’t follow that line of thinking and I am with them.

Walter Hungerford was the first person killed under that statute but he was also accused of raping and abusing his daughter. Either he was a particularly nasty human being for that crime of abuse or its another case of pile on the charges and don’t bother about the truth. In Florence and Venice it was common practice to denounce people in an anonymous manner and one of the most common accusations was homosexuality and that like heresy or witchcraft was a good way to get rid of someone and profit from the denouement because one might get their property. I can imagine that we would certainly have recorded if any of those accused of adultery with Anne were known for perverse sexual practices because they would have been denounced. No matter what language was used, our Tudor ancestors disapproved of same sex relationships because they were believed to be perverse, unnatural, against the law of God and unholy. That nobody did make any such complaints suggested that either George Boleyn or William Brereton or anyone else involved were either super secret or were not practicing gay sex. The worst they might have been involved in was adultery which wasn’t a criminal offence. I am not saying adultery with the Queen but with women other than their wives. Poems written by Cavendish after their deaths accused them of all kinds of sexual acts but seriously, are they evidence or gossip? Without any real evidence, I doubt they were anything but men who liked the ladies a bit too much.

also all theories should be challenged and discussed however daft they sound ,its by questioning these theories that you find the truth ,and not by blindly accepting what one personally and needs to believe in however unpalatable the truth may be so i believe in questioning everything whether it be fact or fiction .

That’s exactly what this article does, Margaret. It challenges a daft theory.

Exactly, that’s my aim in running this website. I was always taught to question everything and to challenge things that weren’t based on fact. I also think that that is what Clare is doing in this article, challenging they myth that has grown out of a theory put forward by one historian years ago now.

I tend to see red when people read fictional works or watch a movie or television show about a historical event or person and take it as fact. If George had homosexual relationships (with the attitude towards homosexuality at the time) this would have only furthered the trump up charges as it could have been rolled into the whole incest allegation as well this man is capable of anything sexual.

I have never been a big fan of Anne Boleyn’s but I still can feel sympathy for her and the others that Henry chose to condemn simple in an effort to rid himself of her. It is sad that on top of false accusations against them, people continue through the ages to embroider and throw speculations out like facts.

Thanks for the wonderful article!

I would just add that while homosexuality existed as it does today and our views have evolved, in those days they were NOT evolved, and if that was a charge that could be laid, then most certainly I would think that they would just come out and happily charge him openly for “buggery” to add to the rest of his offenses.

Thank you for this enlightening post. I still want to retain the belief that Jane Boleyn was a shrew, mainly because she was so excellently portrayed in that way in the 1971 Masterpiece Theatre production! However, I’m now letting myself view her in a warmer light. Thank you for vindicating George, too! I think of him standing there on the scaffold, accused of much that he wasn’t guilty of, and feel ashamed that I was so ready to believe the worst about him. I’ll be better prepared now to read historical fiction with a more jaundiced eye!