As a result of my previous two articles on Hans Holbein the Younger’s “The Ambassadors”, my good friend Robert Parry, author of the wonderful “Virgin and the Crab” and a bit of expert on astrology, has kindly looked at the astrological line-up for Good Friday 1533, the 11th April (Old Style), the date which is shown on the celestial globe, the cylinder sundial and quadrant.

Here is what Robert found:-

The Ambassadors and the Astrological Line-up for Good Friday 1533

by Robert Parry

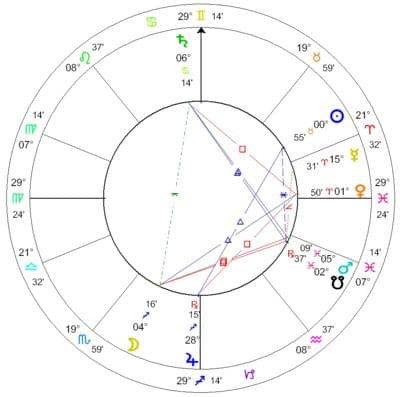

I have checked the astrological line-up for 11 April 1533 (Old Style) and there is a certain unusual configuration evident that does not occur too often.

In astrology every sign of the zodiac has a ruling planet – i.e. Aries is ruled by Mars. But a planet can also be influenced or ‘disposed’ of by whatever other planet rules the sign it is placed in. Example: Mars if found in Pisces is said to be disposed by the planet that rules Pisces, namely Jupiter. So at any given time, most planets have dispositors, that is, other planets that rule the signs they are placed in. Sometimes, however, a planet is found in its own sign – i.e. If, as here, Jupiter is in its own sign of Pisces, then it is particularly strong and can, by definition, have no dispositor.

In the chart of 11th April 1533, however, every planet bar one is in a sign other than its own. And all of these are disposed by other planets, which are in turn disposed of by others in a chain that leads ultimately to just one body that is called the Final (or Grand) dispositor. That body is Jupiter – in its own sign of Sagittarius.

Here’s how it goes:-

- The Moon is in Sagittarius – disposed of by Sagittarius-ruler Jupiter.

- Mercury is in Aries – disposed of by Aries-ruler Mars which in turn is in Pisces, disposed of by Pisces-ruler Jupiter.

- Venus is in Aries – disposed of by Aries-ruler Mars which again is in Pisces, disposed of by Pisces-ruler Jupiter.

- The Sun is in Taurus – disposed of by Taurus-ruler Venus which in turn is in Aries disposed of by Aries-ruler Mars which in turn is in Pisces ruler by Jupiter.

- Mars is in Pisces – disposed of by Pisces-ruler Jupiter.

- Saturn is in Cancer, disposed of by Cancer-ruler the Moon, which is in Sagittarius, also ruled by Jupiter.

So, in other words everything boils down to Jupiter which is in its own sign of Sagittarius and becomes the planet that disposes of all the others. It is what is called the Final or Grand Dispositor of the entire chart. All this would have been viewed as important and relevant in terms of medieval astrology in particular, and would have been significant for anyone looking at the heavens on that date.

So what does it mean?

Jupiter is symbolic of the supreme deity, Zeus in Greek Mythology, but also of the Church. Though strong in its own sign, it is however retrograde (appears to be travelling backwards in the sky), which signifies disharmony – things going backwards, awry. It lends weight to the widespread symbolism of disharmony shown elsewhere in the painting. So yes, the whole thing might well be an allegory on the state of inevitable religious division that is about to occur and which would probably have been obvious to learned men and women everywhere at the time. The fact that this occurs at Easter that year would also have been seen as significant – in a sense the new beginning of the year. The very layout of the picture, two friends divided by a table of scientific and musical equipment is the most basic demonstration of this notion. The humanist movement and scientific developments were forcing the change everywhere. The old ways had to go, and an awful lot of sacrifice was perhaps seen as inevitable as the struggle began to take shape.

Claire’s Thoughts

Thank you so much, Robert, for taking the time to look at the astrological line-up for Good Friday and explaining it in such an easy to understand way. I must admit that much of what John North wrote about astrology in his book “The Ambassadors’ Secret” went over my head!

What I find interesting is that we can look at this painting with hindsight and know that there was a massive change on the horizon. Easter was very much the turning point in 1533 – The Act of Restraints in Appeals (the first part of the process to make Henry VIII head of the Church) had just been passed, Thomas Cranmer had just been made Archbishop of Canterbury, convocation had ruled that the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon was invalid, a pregnant Anne Boleyn went to mass on Easter Saturday as queen after being recognised so by the royal court on Good Friday and plans were being put in place for her coronation. England was on the verge of breaking with Rome and 1533 would see Henry VIII being excommunicated by the Pope. An amazing chain of events and all to do with religious division and disharmony.

Robert mentioned the two friends in the painting being separated by the table of scientific and musical objects and how this also symbolises division, and this got me thinking as to whether Jean Dinteville, the French ambassador and a courtier, symbolised the State and politics and Georges de Selve, an ambassador but also the Bishop of Lavaur, symbolised the Church. In the painting these men, State and Church, are being divided/separated by objects that are pointing to Good Friday. Am I reading too much into it?!

Other Thoughts

Olivia Peyton, who I mentioned in my previous two articles, posted a comment on our Anne Boleyn Files Facebook page:-

“While I was reading your post, it hit me that of all Holbein’s surviving works, I do believe this is the largest in dimension. Since most of the Tudor courtiers paid Holbeing to paint smaller portraits of themselves, the sheer size of this work alone points to royal patronage, in my estimation.”

She’s right, The Ambassadors is huge! It measures 207 x 209.5 cm. Does the size and scale of it point to Anne Boleyn, Holbein’s patron, commissioning it?

Olivia also pointed out that in 1533 Marguerite of Navarre “took a lot of heat for her ideas, so, maybe the painting was too hot to hang at her brother’s court – perhaps Anne in her enthusiasm to record for all posterity the secret she shared with the French royals was a tad too implicit? So they stashed it at Polisy, perhaps.” That could explain why, if Anne Boleyn commissioned it as a present for Marguerite’s birthday on Good Friday, the painting actually ended up at Dinteville’s chateau at Polisy, rather than at the French court.

I’m left thinking that when you analyse this painting, and try and figure out its message, you’re left with more questions than you began with!

I would love to think that Anne Boleyn did have a hand in this painting, wouldn’t you?

What are your thoughts on the symbolism of the painting? Go to http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/ARTH214/ambassadors_hot_spots.htm and http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/ARTH214/Ambassadors_hotspots_texts.htm

and explore the hotspots on the painting then let me know your thoughts.

P.S. Robert Parry has just started his own author’s blog at http://endymion-at-night.blogspot.com/ and he’s also running a competition to guess the title of his next novel – see http://endymion-at-night.blogspot.com/p/competition-can-you-guess-title-of-my.html. I can’t wait to read his next book!