As I said in my previous article, “Holbein’s The Ambassadors: A Renaissance Puzzle? – Part One: Context”, The Ambassadors is a Renaissance puzzle, a code in a painting, a message to be fathomed.

It may look like a portrait of two men, two ambassadors, but in “The Ambassador’s Secret”1, John North writes of how the most important part of the painting is the still life right in the centre, the centre panel, and not the two men positioned at the sidelines.

The Ambassadors is full of signs and symbols, and there are many different views on what the objects in the painting symbolize. Today, I am going to look at the different objects in the painting and discuss what they might mean.

I have used the painting from Wikimedia Commons to produce the close-ups of the various items in the painting but you will find the following links helpful:-

- http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/ARTH214/ambassadors_hot_spots.htm – This allows you to click on things in the painting and get close-ups and also zoom in.

- http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/ARTH214/Ambassadors_hotspots_texts.htm – This allows you to click on the things and find out more about them.

The Floor

The traditional view of the mosaic floor in Holbein’s The Ambassadors is that it is a copy of the medieval Cosmati pavement in the sanctuary of Westminster Abbey, the sacred area in front of the abbey’s high altar, a floor that is similar to the one beneath Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” in the Sistine Chapel.

The Westminster Abbey floor had three inscriptions, one expressing the year as 1268 and identifying the work as that of Odoricus, the Roman mosaic maker, the second predicting the duration of the world (19,683 years – North p212) and the third, which is on the central circle and which tells us that the pattern “represents the Macrocosm – the universe as a whole, in contrast to mankind within it, the Microcosm”. The third inscription, therefore, “clearly establishes the cosmological significance of the pavement as a diagram of the universe”, and according to the State University of New York College at Oneonta website:-

“It establishes a relationship of the men, as signifying the microcosm, to the rest of the painting and to the world as a whole, the macrocosm. This relationship establishes the central position of man in the Renaissance conception of creation.”2

Yes, slightly over my head too!

However, some people don’t see the floor in the painting as a copy of the Westminster Abbey Cosmati pavement at all because it is not an accurate copy. John North cites P. C. Claussen, an expert on Cosmati pavements as interpreting the floor to represent that Dinteville and Selve are standing on “double ground”, on both the territories of London, where the ambassadors actually were, and Rome. Richard Foster suggested that the floor could be the floor of the palace at Bridewell, where the ambassadors were staying, or at Greenwich Palace, one of Henry VIII’s favourite palaces:-

“To claim that Holbein’s floor is anything more than the vaguest reflection of the Westminster pavement would be to overstretch credulity. By contrast, the more practical and logical location of Greenwich may be suggested without an appeal for artistic license. The floor of Holbein’s picture is most likely not a representation of any real cosmati pavement at all but a painting of a painting: a wooden floor in Greenwich Palace painted by craftsmen, working perhaps from a pattern book, in imitation of what was to them an ‘antike’ (antique) work pavement – the cosmati designs of Italy.”3

John North points out that Holbein’s floor has a six-pointed star in the middle of it which he thinks could symbolise God having created the world in six days as well as being a symbol of the Trinity twice over.

The Instruments

John North writes of how the instruments on the upper shelf in the central panel of the painting are “designed to reflect on the state of the heavens”, while those located on the lower level are concerned with “the affairs of the world below”, but what exactly do they symbolise?

The Celestial Globe

If you look at a close up of the celestial globe –click here – you will see that the constellations are shown not as stars but in the form of their mythological counterparts. The one that catches our attention is Cygnus the Swan which is marked “Galacia” and Mary Hervey4 suggests that the c*ck-like form of the bird was referring to the Gallic symbol, the c*ck, and so was symbolising “the onslaught of France upon her foes, and their ultimate downfall and flight”, and was also referring to the home country of the ambassadors. North agrees that this theory is not “implausible”, particularly when the globe also displays the constellation of the Dolphin labelled as “Delphinus” which is the source of the word “Dauphin” the name given to French Kings’ eldest sons.

John North states that the celestial globe has been set to show a date of the 11th April 1533, Good Friday and the day when the royal court was informed that Anne Boleyn was queen, but the latitude is not set for London which is where the painting was painted. The Oneonta website points out that the latitude, which is set between 42 and 43 degrees, actually corresponds to Spain or Italy and cite Dekker and Lippincott as observing that 16th century astronomical tables listed 42 degrees north as the latitude of Rome. Perhaps “this might be intended to hint at the differences in the political and religious points of view between London and Rome”.5

Cygnus

As I’ve already said, the main constellation visible on the celestial globe is Cygnus, and John North points out that one of the key lines of the painting passes through Deneb, the brightest star of Cygnus, up to the head of Christ. Also, North states that the constellation of Cygnus was traditionally associated with the cross of Christ and that its stars formed a Latin cross.

The Cylinder Sundial

According to John North, this cylinder sundial is for latitudes in the London area and shows the time of 8.15am or 3.45pm on the 11th April 1533.

The Quadrant

The white quadrant concurs with the cylinder sundial and shows a time of 4pm on the 11th April 1533.

The Polyhedrial Sundial

John North talks of this sundial as being a riddle and the Oneonta website states that the times shown on its different surfaces just do not agree. On one side it is showing 9.30 and on another it is showing 10.30, and it has also been set to the latitude of North Africa, not London! Very odd. Oneonta suggests that it may be related to “the theme of limitation of human science which is limited by the finite nature of humanity.”

The Torquetum

This is the instrument located above de Selve’s right elbow. It is an astronomical instrument and John North writes that “the instrument as a whole has been so positioned that the zodiacal place of the sun on Good Friday 1533 is at the nearest point of the appropriate (ecliptic) disc to the viewer” and that the latitude has been set within a degree of London’s latitude, i.e. 51.5º.

The Turkey Rug

John North writes of how the Turkey rug, on which the celestial instruments are placed, was chosen for its geometrical pattern, which supported “the geometrical scheme underlying the painting as a whole, and that the one shown in the painting was from a “Christian religious tradition that also had a cosmic component”.6 North also writes that the symbols “S” and “E” which can be found on the rug denote “God Almighty” and “Jesus”.

The Terrestrial Globe

John North makes some observations about the terrestrial globe shown in The Ambassadors: it shows Dinteville’s estate at Polisy in France, Rome is painted more or less at the geometric centre of the globe and the globe also shows the coastline of the Americas, the New World. He theorizes that the depiction of the coastline of the Americas (plus Oneonta point out that “the line demarcating the division of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial possessions that was established by the Pope in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494” is shown) would have stirred in the French ambassadors “the embers of resentment at the papal allocation of the New World to Spain and Portugal alone”.7

The Oneonta website puts forward the idea that Polisy is marked on the globe to emphasise Dinteville’s position as a nobleman and that the arithmetic book (see below) is a merchant’s arithmetic book which refers to de Selve’s background, the fact that his family used to be merchants in the Limousin.

The Arithmetic Book

The book shown in the painting has been identified as Peter Apian’s “Eyn newe unnd wohlgründte underweysung aller Kauffmanss Rechnung in dreyen büchern” from 1527. It is open on a page which shows three examples of long division which open with the word “Dividirt” which, when combined with the appearance of the fraction “1/2” could symbolise political and religious division and disharmony, something which de Selve was concerned about.

The Lute with the Broken String

The Oneonta website points out that “the lute along with the case of flutes and the Lutheran Hymnbook represents music as one of the disciplines of the Quadrivium”, with the Quadrivium being the four arts taught in medieval universities: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. Mary Hervey noted the connection between this lute with its broken string and the lute emblem depicted in Andrea Alciati’s 1531 Emblematum Liber which says underneath it:-

“Take, O Duke, this lute whose form is said to come from a fishing boat, and which the Latin Muse claims as her own. May our gift be pleasing to you at this time, as you prepare to undertake new treaties with your allies. It is difficult, unless the man is skilled, to tune so many strings, and if one string is not well stretched, or breaks (which happens easily), all the pleasure of the shell is lost, and the splendid song becomes absurd. So the princes of Italy join together in alliances: there is nothing for you to fear if your love remains harmonious. But if anyone withdraws, then, as we often see, all that harmony diminishes into nothing.”8

Oneonta states that Alciati was using the commonplace idea of musical harmony to symbolise heavenly harmony and both North and Oneonta suggest that the lute, when taken with the case of flutes, which has one missing, symbolises discord.

The lute with the broken string and the missing flute could also be taken to symbolise the imperfection of the world compared to God’s perfect creation, an acknowledgement that our world is far from perfect and that we need God’s help.

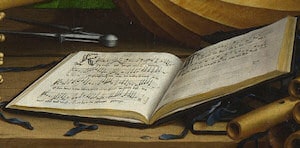

The Lutheran Hymnal

The hymnal in Holbein’s painting is open at two pages which are not consecutive in the actual hymnal by reformer Martin Luther and so have been out together deliberately. The page on the left shows Luther’s “Kom Heiliger Geyst Herre Gott” which was his translation of the hymn “Veni sancte Spiritus”, “Come Holy Ghost”. The page on the right shows the hymn “Mensch wiltu leben seliglich und bei Gott bliben ewiglich…”, which was the introduction to his version of the ten commandments.

Mary Hervey was of the opinion that the choice of hymns was “an expression of hope for the reunion of the Roman and Reformed churches”7, Oneonta puts forward the idea that the juxtaposition of these hymns is to do with the “principal theme of Luther’s thought: the contrast between the Law and the Gospel, or Law and Grace” which is “directly tied to one of the central tenets of Luther’s theology, Justification by Faith”. Oneonta points out that the writings of Georges de Selve reflected the importance of the question of justification. John North looks at the numbering of the hymns, the fact that the first hymn is numbered XIX , (19), yet in the original hymnal it was numbered XII. North thinks that this is a deliberate allusion to Easter because the rules of Easter make use of a 19 year cycle, something that every educated person of that time knew.

Both John North and Kate Bomford also note that the lute’s tapering wooden shell is reminiscent of a coffin and so acts as a memento mori, a reminder of death.

The Distorted Skull

The Oneonta website says that “the inclusion of the skull makes explicit the essential finiteness of man and the limitation of human knowledge” and that Holbein’s choice of an “anamorphic representation” reinforces the theme of human limitation and that “Holbein seems to be opposing human vision, as a metaphor for understanding, to that of God. Human vision and knowledge are necessarily limited by time and place, while God can see and know all things at all times.” Another reminder of this is the skull badge on Dinteville’s hat.

The Oneonta website also looks at the placement of the skull in relation to the floor, and how its position symbolises the way that “human mortality obscures a true vision of God”, and its relationship to the crucifix in the top left corner of the painting. The pairing of the skull and crucifix is seen in the 16th century engraving of St Jerome in His Study by Albrecht Durer and Joos van Cleve’s painting of St Jerome, where “Jerome serves as the model of the Christian scholar whose life dedicated to lectio divina makes him profoundly aware of human mortality and the necessity of Christ’s passion as the only means to victory over death.”Oneonta But perhaps the pairing is also a reminder of Golgotha or Calvary, the Place of the Skull, where Christ was crucified and where, according to tradition, Adam was buried, “thus the blood of Christ’s passion cleanses the sin of Adam” Oneonta.

John North also points out that the skull in the painting casts a unnatural shadow, one that lies at the wrong angle when the rest of the painting is taken into account, but that the angle of the shadow is right 4pm on the afternoon of Good Friday.

The Half-Hidden Crucifix

It seems strange that the crucifix should be barely visible in the top left corner of the painting and half-hidden by the curtain if Good Friday is one of the main themes of the painting. But, John North, in looking at the various lines of sight in the painting talks about how if you choose the gnomon (the part of the sundial that casts the shadow) on the nearer side face of the polyhedral sundial then “the eye is led through various potentially significant points until it reaches the head of the crucified Christ.”8

It seems strange that the crucifix should be barely visible in the top left corner of the painting and half-hidden by the curtain if Good Friday is one of the main themes of the painting. But, John North, in looking at the various lines of sight in the painting talks about how if you choose the gnomon (the part of the sundial that casts the shadow) on the nearer side face of the polyhedral sundial then “the eye is led through various potentially significant points until it reaches the head of the crucified Christ.”8

John North talks about how the painting is inviting us “to look upwards to contemplate Christ after he had made the ultimate sacrifice, and to look down to a symbol of death and the place of death, to which Christ has for the time being descended, and which by that sacrifice he will vanquish.”9

The Green Curtain

John North believes that the division of the green curtain could be alluding to the tearing of the temple curtain in the crucifixion story, but Olivia Peyton10 wonders if it is actually symbolising “la langue verte”, also known as the Green Language or the Language of Birds. The language of birds in medieval literature was a “mystical, perfect divine language” wiki and in alchemy, Renaissance magic and Kabbalah it was seen as a secret and perfect language and the key to perfect knowledge. The Troubadours of medieval France used it as a secret language. Perhaps this hints at the secrets in the painting, the secret knowledge.

Kate Bomford11 wonders whether the curtain is symbolic of the division between the earthly and heavenly realms, like curtains were used in churches and temples.

The Two Men

As I said in my previous article, Kate Bomford wrote of how Holbein had evoked marriage portraiture in his placement of Dinteville and Selve in order to show that the two men were friends. However, Margaret A. Tottle-Smith, author of “Fruit of the Vine”12, writes of how we get a portrait of identical twins if we slide the two images across in a mirror and that the The Ambassadors could be a painting of the twins Yeshua and Judah, Jesus and his identical twin (or some believe) Judah-Thomas.

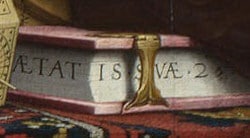

Dinteville’s Dagger and de Selves Book

Dinteville is depicted with a dagger in his hand, one of the symbols of a French nobleman, and his dagger bears the inscription “ÆT. SVÆ 29” – click here for a close up image of the dagger which you can also zoom in on – which corresponds to Dinteville’s age in 1533, i.e. 29. The book de Selve is leaning on bears the inscription “AETAT/IS SV Æ 25” corresponding to de Selve’s age in 1533, i.e. 25.

John North notes that Dinteville’s dagger points to Jerusalem on the globe(although I’m not sure that we can be that precise) yet Rome is at the centre of the globe. Could this be suggesting that Rome, the centre of the Catholic Church and which held supremacy in all matters of faith, was deaf to the true message of Christ? I think not, but it is an interesting suggestion.

Dinteville’s Order of St Michael

Although this medallion could have no symbolism at all, in that Dinteville simply chose to wear it, the fact that St Michael is the archangel who fights the heavenly battle against the Devil in the Book of Revelation could symbolise the triumph of good over evil. St Michael was also the archangel of light.

The Number 27

John North notes the recurring theme of the number 27: the solar altitude of 27º on the quadrant, its occurrence on the polyhedral dial, the angle 27º on the torquetum, the fact that two of the divisions in the arithmetic book produce answers which are multiples of 27, the angle between the visible edges of the hymnal’s covers is 27º, the axis of the elipse of the skull is within half a degree of 27º and the angles of the various lines of sight in the painting. The importance of the number 27 is that 27º was the altitude of the Sun at a few minutes past four on Good Friday 1533 and “that it is precisely the angle at which the foreground anamorphosed skull is drawn, so that the skull may be treated as a visual record of the shadow cast by the Good Friday Sun at the end of the hour following Christ’s death on the cross.”13

The Sun

John North discusses how the Sun has been used throughout the history of the Christian Church to symbolise Jesus Christ and her in The Ambassadors it also symbolises Christ. North points out that “the Sun on the globe is in shadow and below ground, reminding the contemplative viewer of the gloomy situation on the evening of Good Friday” and goes on to say that there are three solar symbols on the upper line of sight in the painting, plus Christ himself, contrasted with the lower line which is “one of natural shadow, cast by the skull, a reminder of corruption and death.”

The Right and Left Eyes

This painting with its anamorphic skull requires the viewer to stand to the side, rather than looking at it from the front. The various lines of sight in the painting are too difficult to explain in this article but John North notices that if you stand to the right of the painting “it is the left eye that looks down to the skull and the ravages of time on the created body, and the right that looks up, to Christ on the cross and the eternal verities, in the far corner of the painting.” North writes of how Thomas à Kempis wrote, in the early 15th century, about how “with the right eye we stand above the present and look upon the eternal and things heavenly, while with the left eye we behold things transitory”14, so perhaps Holbein was thinking about this when he developed the lines of sight in the painting.

The Gloves

De Selve is holding a pair of gloves in his right hand and these are black, the liturgical colour for Good Friday.

Seal of Solomon

Half-obscured by the skull in the painting is a hexagram, a Star of David or Seal of Solomon. In Medieval Christian, Jewish and Islamic legends, the Seal of Solomon was a signet ring which belonged to King Solomon, a magic ring which allowed him to speak to animals and command demons and jinni. In alchemy, the Seal of Solomon is a combination of the symbols for fire and water, opposites, and is “all that is unified in perfect balance”15. According to North there are also other hexagrams present in the picture and the hexagram symbol “could so easily draw together theologians and alchemists, magicians and writers on the cosmic order… because it was seen by all of them as a sign of some sort of power, a power that was largely unknown and in that sense mystical, but a power that was nevertheless considered to be real and physical. Above all, it could be discussed in a familiar language, that in which they were accustomed to speak of the Holy Spirit.”16

Memento Mori

Some people view The Ambassadors painting as a memento mori, a reminder of death and our mortality, or a “vanitas”, a reminder that life is fleeting and not to put store in earthly treasures. Such works of art would contain skull imagery. The Ambassadors contains two obvious memento mori, the anamorphic skull and the skull badge on Dinteville’s hat.

The Constellation of the Lyre and the Falling Bird

If you look at the close-up image of the celestial globe – click her – you will see the constellation of the Lyre (Lyra), above the swan/cock, which is labelled as Vultur Cadens (the Falling Bird) by Holbein and represented as a falling eagle. John North ponders whether the name “the Falling Bird” and the representation of the eagle could be referring to the Imperial Eagle. Was Holbein “simultaneously glorifying the Gallic c*ck and denigrating the Imperial Eagle?”17 North thinks not.

The Ram

If you look again at the close-up image of the celestial globe – click here – you can see a two ram’s heads supporting the globe and North writes that on the 11th April 1533 the Sun had entered the second degree of the sign of Taurus, that “the constellation of Aries, the Ram was mainly situated in the sign of Taurus” and that “the Sun would have been just below the head of the Ram”18 on the celestial globe. He believes that this may have been part of the reason for using the ram’s head supports, but that there are also many references to Jesus Christ as a ram in Christian writings and that Christ as the Lamb of God is often depicted as an animal with horns, a ram rather than lamb. Could the fact that one of the lines of sight passes through the Sun’s place on the celestial globe, in the constellation of the Ram, on its way up to Christ on the cross be speaking to us about Christ being the sacrificial lamb?

General Themes

As you can see from the theories regarding the symbolism of these various objects, there are common threads or themes:-

- Memento mori – The inevitability of death.

- The contrast between the worldly and spiritual realms.

- The vanity of scholarship, science and the arts when contrasted with the truth of Jesus Christ.

- Cosmic harmony and unity.

- Easter – The sacrifice of Jesus Christ, the shadow of death but the light and hope we have from his sacrifice.

- Political instability, religious division and disharmony.

- Shadow and light – The gloom of the crucifixion but Jesus as the Light of the World.

- Creation and redemption.

- The Holy Spirit and the hope that it would unify the Church.

- Justification by faith – Luther’s idea that we are justified by faith and not good works. It is Christ’s sacrifice on the cross which gives us salvation and eternal life, not our actions or deeds.

- Christ’s victory over death.

- Friendship – A celebration of the friendship between Dinteville and de Selve.

Kate Bomford, in her article “Friendship and Immortality: Holbein’s The Ambassadors Revisited”19 wonders if the painting actually has more to do with the men’s relationship, their friendship, and their own personal triumph over death and Satan as men of God – a celebration of their “attainment of the heavenly immortality or salvation, to which the work alludes.” She also wonders if Dinteville commissioned it so that he could reflect on his “place in the eschatological scheme, thus repenting of past sines and resolving to live thereafter in greater virtue”, after all, Bomford reminds us that his stay in England was marred by his ill health, or to act as a reminder to those who viewed it to remember Dinteville and De Selve in their prayers (after their deaths) so that their souls could be released from Purgatory.

The Oneonta website concludes that The Ambassadors’ true subject matter is “what is unrepresentable and unknowable –God. What is represented is a network of signs that leads us to this true reality hidden in the world of appearances” and that it “asks us to see invisibly the invisible truth which is hidden behind the surface of appearances.”

But who commissioned the work?

- Jean Dinteville? – Kate Bomford points out that he is the prominent figure in the painting and we can see that he is positioned standing further forward. His broad shoulders and dress definitely make Dinteville the more eye-catching of the two. As a nobleman he also had the money to pay for such a work of art. We also know that it was in Polisy, Dinteville’s chateau, in 1589 because it is listed on the inventory.

- Anne Boleyn? – As I wrote in my previous article, Anne was Holbein’s patron and he was working on some montages for her coronation, so did she commission this painting and for what purpose? The painting is full of religious messages and reformist ideas and we know that Anne was of a reformist persuasion and had been exposed to radical ideas during her time in France, but that doesn’t explain why she would commission Holbein to paint two French ambassadors. Olivia Peyton and Robert Mylne have put forward the idea that she had it painted for her old friend Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, but then why did it end up hanging in Polisy? Did Anne change her mind? It’s a mystery!

- Henry VIII? – Although Holbein was working at the English court and Dinteville and De Selve were visiting the court for diplomatic reasons, I don’t see any reason to think that Henry had any hand in this painting whatsoever.

- Person Unknown – Perhaps the Dinteville family?

We just don’t know who was really behind this painting or what the real message of it is. I’m not sure I want to know, I enjoy looking at it and puzzling over the details.

Notes and Sources

- The Ambassadors’ Secret, John North

- The Oneonta Website – Various pages on The Ambassadors

- “Patterns of Thought: The Hidden Meaning of the Great Pavement of Westminster Abbey”, Richard Foster, p60, cited by Olivia Peyton on the Anne Boleyn Facebook Page

- Holbein’s Ambassadors: The Picture and the Men, Mary Hervey (1900)

- The Oneonta Website – Various pages on The Ambassadors

- North, p150

- Ibid., p153

- Andrea Alciati’s Emblematum Liber (1531) quoted on the Oneonta website

- Cited on p163 of North

- North, p173

- North, p327

- Olivia Peyton, Anne Boleyn Facebook Page

- “Friendship and Immortality: Holbein’s Ambassadors revisited”, Kate Bomford, Renaissance Studies Vol. 18 No. 4

- Fruit of the Vine, Margaret A Tottle-Smith

- North, p252

- North, p180-181

- Seal of Solomon, Wikipedia article

- Ibid., p267

- Ibid., p296

- Ibid., p115

- “Friendship and Immortality: Holbein’s Ambassadors revisited”, Kate Bomford, Renaissance Studies Vol. 18 No. 4