Today I welcome author Susan Higginbotham to The Anne Boleyn Files. Susan has written a few historical novels (they’re brilliant!) but her latest book is non-fiction and it focuses on the Woodville family – The Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England’s Most Infamous Family. Thank you, Susan, for this excellent article on Elizabeth Woodville.

Today I welcome author Susan Higginbotham to The Anne Boleyn Files. Susan has written a few historical novels (they’re brilliant!) but her latest book is non-fiction and it focuses on the Woodville family – The Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England’s Most Infamous Family. Thank you, Susan, for this excellent article on Elizabeth Woodville.

Elizabeth Woodville, queen to Edward IV, has acquired a reputation for pride and haughtiness, enshrined in many a historical novel. One incident in particular stands out as proof of the queen’s insufferable pride: a banquet where the queen dined in solitary splendor while her guests dined in utter silence.

Following childbirth, a medieval mother was expected to remain in her chamber for about a month, after which a purification/thanksgiving service known as a “churching” would mark her return to public life. For a medieval queen, a churching was a particularly grand event—in 1453, Elizabeth’s predecessor, Margaret of Anjou, had invited an impressive roster of duchesses, countesses, and other ladies to attend her own.

An observer from Nuremburg, Gabriel Tetzel, travelling in the suite of Leo of Rozmital, a Bohemian nobleman, visited England in 1466. Gallantly, he wrote that England bred “women and maidens of outstanding beauty,” whose dresses had trains longer than Tetzel had seen in any other country. Tetzel also found that the English were struck by the length of his hair, and he noted the English preference for kissing over handshakes: “[W]hen the guests first arrive at an inn the hostess comes out with her whole family to receive them, and they have to kiss her and all the others. For with them to offer a kiss is the same as to hold out the right hand; for they do not shake hands.”

Tetzel happened to be on hand in 1466 to witness Elizabeth’s churching, which took place a month or so after the birth of her first child by Edward IV, Elizabeth of York, on February 11, 1466. He reported:

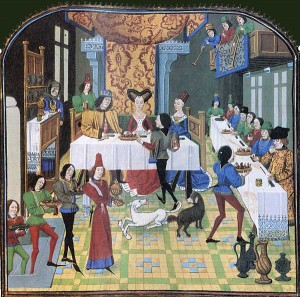

“The Queen left her child-bed and went to church in stately order, accompanied by many priests bearing relics and by many scholars singing and carrying lights. There followed a great company of ladies and maidens from the country and from London, who had been summoned. Then came a great company of trumpeters, pipers and players of stringed instruments. The king’s choir followed, forty-two of them, who sang excellently. Then came twenty-four heralds and pursuivants, followed by sixty counts and knights. At last came the Queen escorted by two dukes. Above her was a canopy. Behind her were her mother and maidens and ladies to the number of sixty. Then the Queen heard the singing of an Office, and, having left the church, she returned to her palace in procession as before. Then all who had joined the procession remained to eat. They sat down, women and men, ecclesiastical and lay, each according to rank, and filled four great rooms.”

Rozmital and Tetzel went into a separate hall with England’s noblest lords “at the table where the King and his court are accustomed to dine.” There an unnamed earl, quite possibly Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, sat in the king’s place and was shown all of the honor customarily shown to the king. The breathless Tetzel reported, “Everything was supplied for the Earl, as representing the King, and for my lord [Rozmital] in such costly measure that it is unbelievable that it could be provided.”

Having finished dining, the earl conducted Rozmital and his attendants “to an unbelievably costly apartment where the Queen was preparing to eat.” There, Tetzel, watching from an alcove so that his lord “could observe the great splendour,” noted:

Having finished dining, the earl conducted Rozmital and his attendants “to an unbelievably costly apartment where the Queen was preparing to eat.” There, Tetzel, watching from an alcove so that his lord “could observe the great splendour,” noted:

“The Queen sat alone at table on a costly golden chair. The Queen’s mother and the King’s sister had to stand some distance away. When the Queen spoke with her mother or the King’s sister, they knelt down before her until she had drunk water. Not until the first dish was set before the Queen could the Queen’s mother and the King’s sister be seated. The ladies and maidens and all who served the Queen at table were all of noble birth and had to kneel so long as the Queen was eating. The meal lasted for three hours. The food which was served to the Queen, the Queen’s mother, the King’s sister and the others was most costly. Much might be written of it. Everyone was silent and not a word was spoken. My lord and his attendants stood the whole time in the alcove and looked on.

After the banquet they commenced to dance. The Queen remained seated in her chair. Her mother knelt before her, but at times the Queen bade her rise. The King’s sister danced a stately dance with two dukes, and this, and the courtly reverence they paid to the Queen, was such as I have never seen elsewhere, nor have I ever seen such exceedingly beautiful maidens. Among them were eight duchesses and thirty countesses and the others were all daughters of influential men.”

For the Woodvilles’ modern detractors, this grand, silent meal, where even the queen’s mother and the king’s sister were obliged to kneel, epitomizes the queen’s vanity and the social climber’s insecurity. Tetzel’s editor, even while acknowledging that silence at meals at the time was not unusual, commented that Elizabeth’s “head must have been turned by her sudden elevation in rank.” This, however, was no ordinary family dinner but a grand occasion for the royal family, marking Elizabeth’s safe delivery of the king’s first legitimate child. Notably, nothing in Tetzel’s account suggests that he found Elizabeth’s conduct repellent; he seems to have been merely a fascinated observer, just as he was when he witnessed the unnamed earl dining in royal state. Most likely, Tetzel, who described Edward’s court as “the most splendid court that could be found in all Christendom,” regarded the meal as just another example of its magnificence.

Other glimpses of Elizabeth, moreover, paint a different picture, and even a charming one, of the queen at home. In 1465, her oldest brother Anthony, coming from mass, was kneeling before the queen when he was surrounded by her ladies, who tied a collar of gold around his right thigh and dropped a billet in Anthony’s cap, which he had removed from his head while kneeling before Elizabeth. Anthony quickly perceived that he was being charged with performing a chivalric enterprise, whereupon he dutifully issued a challenge to the Bastard of Burgundy, not through arrogance, presumption or envy, he explained, but only to obey his fair lady.

In 1472, Louis de Bruges (Lodewijk van Gruuthuse), who had assisted Edward IV and his companions during their exile in 1470-71, came to England as an honored guest of Edward IV, who created him Earl of Winchester. The King conducted Louis to Elizabeth’s chamber, “where she sat playing with her ladies at the morteaulx [a game similar to bowls] and some of her ladies and gentlewomen at the closheys of ivory [ninepins], and dancing. And some at divers other games accordingly. The which sight was full pleasant to them.” The next day, after Elizabeth hosted a banquet for Louis in her own chambers, the king, the queen, and the queen’s ladies and gentlewomen escorted Louis to his three rooms, hung with white silk and linen and carpeted throughout. Louis was to sleep in a bed “as good down as could be thought,” furnished with sheets and pillows of the queen’s own ordinance.

Plainly, then, all was not frigid silence in Elizabeth Woodville’s household. There were golden chairs and silent meals—but, we should remember, there were also games of ninepins.

Susan Higginbotham’s new book, The Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England’s Most Infamous Family is available now from Amazon.com, Amazon UK or your usual bookstore.