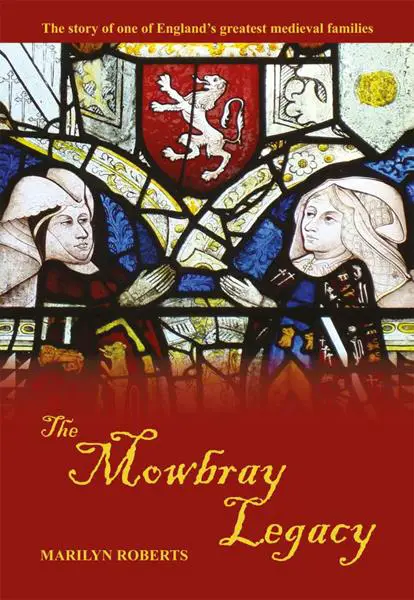

Today we have a guest post from Marilyn Roberts, historian and author of The Mowbray Legacy and Lady Anne Mowbray: The High and Excellent Princess. You can see my review of Lady Anne Mowbray over at our book reviews site – click here. Over to Marilyn…

This is the time of year when thoughts of Tudor enthusiasts turn to the beheading of Katherine Howard who, like her first cousin Anne Boleyn before her, had briefly been the most glittering star in the firmament at the court of King Henry VIII. In the twenty-first century the ducal branch of the Howards remains the premier noble family in the land, but had it not been for the untimely death of an eight-year-old girl in 1481, followed in 1483 by the sudden death of King Edward IV and the disappearance of his young sons, the Princes in the Tower, most people might never have heard of them.1

In December 2014 it will be half a century since the lead-encased body of Anne Mowbray, Duchess of York and Norfolk, was discovered on a building site north of the Tower of London, two miles from her supposed resting place. The catalogue of unfortunate errors associated with the removal of her remains from the site and their subsequent scientific examinations, caused an outcry among some leading Establishment figures of the day, and the child had to be reburied before the examinations were completed. The discovery in 1964 caused worldwide interest, but within a few weeks Anne Mowbray was once more consigned to the mists of oblivion.

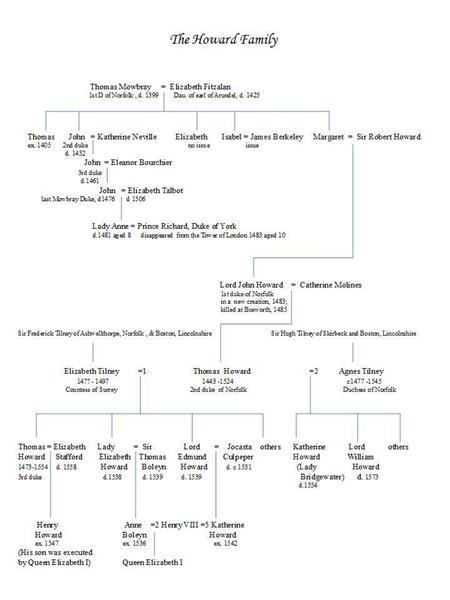

In January 1476, John Mowbray, fourth duke of Norfolk died suddenly aged 31, leaving only a three-year-old daughter, Lady Anne, who, as a female, was not allowed to hold a dukedom in her own right and so was given the lesser title of Countess of Norfolk. Anne’s co-heirs in the event of her death without issue were Lord William Berkeley and Lord John Howard, the elderly sons of Lady Isabel and Lady Margaret Mowbray, two of her great-grandfather’s sisters. Anne, being a minor, became the ward of King Edward IV, who married her off to his own younger son Prince Richard, Duke of York, whom he also made Duke of Norfolk in a new creation. Betrothal at so young an age was by no means unusual, with marriage following some years later, but Anne was five- years-and-five-weeks-old and Prince Richard only four at the time of their nuptials.

The wedding was a magnificent affair that took place at St Stephen’s Chapel in the Palace of Westminster on a chilly January day in 1478. The tiny couple had to go through hours of ritual, totally incomprehensible to them, before the little girl was finally led from the altar by her new uncle-by-marriage, the future King Richard III, then aged twenty-five, whose other duties on that auspicious day included stepping outside among the common people in all his finery to cast gold and silver coins to them from golden basins.

Thus far, then, nothing illegal or remarkably removed from established laws of inheritance had transpired, but the day after the wedding the King’s reason for moving so quickly became abundantly clear when parliament passed legislation allowing the little husband to keep the Mowbray fortune for his lifetime should Anne die childless. Where did that leave the co-heirs, who would, quite correctly, have expected the inheritance to revert to them or their successors in such circumstances? Edward IV had reached an accommodation with Berkeley some months previously that, in return for his acquiescence, his enormous debts, the equivalent of many millions of pounds today, would be settled by the crown. As far as is known, John Howard was to get nothing, but appears not to have protested, perhaps because he was already a very rich man in his own right.

When Lady Margaret Mowbray married Robert Howard of Stoke-by-Nayland in Suffolk around 1420, she married beneath her station, and it is tempting to think this might have been a love match. Although her own financial prospects were not very promising, Margaret, a daughter of the first duke of Norfolk, could claim descent from Henry III and Edward I, among a long list of illustrious others. The impecunious Robert Howard, on the other hand, came from an untitled, yet fairly prosperous, family with lands in Norfolk and in the neighbouring county of Suffolk.

Later generations of Howards tried to embellish the family history by claiming descent from the Anglo-Saxon hero Hereward the Wake, but their origins remain obscure. What is known, however, is that in part they owed their prosperity to marrying local heiresses, and Robert Howard’s father, Sir John, a prominent figure in East Anglia, was no exception. Robert, however, being the son of his father’s second marriage, to a woman of rather modest means, was set to inherit very little.

Whatever the oddly-matched couple’s financial constraints might have been, it was their remarkable son John, a capable military man, a self-made and extremely astute businessman, ship owner, ambassador and loyal Yorkist, who found himself co-heir to Anne Mowbray, to whose hot-headed father he had remained a faithful kinsman, friend and helpmate. It is not absolutely certain that Robert Howard had even been a knight, but by the time of Lady Anne’s death, his and Margaret Mowbray’s son had already been elevated to the first rung of the Peerage as Lord John Howard.

Anne Mowbray, Duchess of York and Norfolk, referred to at her marriage as ‘the high and excellent princess’ died just short of her ninth birthday and, as planned, her little widower kept her fortune in land and property for his lifetime. It did not stop there, however, as the scheming Edward IV had yet more spurious legislation brought before parliament making over the inheritance to himself, should his son also die young.

As we know, the story unfolded very differently from what the King had expected, he dying suddenly in the spring of 1483 just before his 41st birthday and Prince Richard disappearing the following autumn with his brother, the uncrowned Edward V. Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the boys’ uncle, became King Richard III and restored the Mowbray inheritance and titles to Anne’s rightful heirs: William Berkeley became Earl of Nottingham, and John Howard Duke of Norfolk in new creations. Berkeley was of the ‘old’ nobility through and through, but for the Howard family this represented one huge and unprecedented leap from the bottom rung of the Peerage to the very top.

It seems probable that an enterprising, versatile and shrewd man like John Howard would have made the grade anyway, not reaching a dukedom perhaps, but almost certainly gaining high status within the Peerage in reward for loyalty and service. As it happened, though, the Howard family’s elevation to the premier non-royal dukedom was a mixed blessing. Loyal to Richard III, John Howard was killed at Bosworth only two years later, and his badly wounded son Thomas, Earl of Surrey was imprisoned by the victorious Henry VII for four years. Henry VII, though, realised Thomas was a very capable man, politically and militarily, whom he could trust, and he rose to great heights. The young Henry VIII eventually restored the dukedom in 1514, the year after the battle of Flodden, which had made Howard, by now an old man, into a national hero.

In 1524, Thomas, second duke, over eighty when he died, was succeeded by his son, another Thomas, who married a daughter of Edward IV as his first wife; it is this Thomas, third duke and uncle of both Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, with whom Tudor followers are most familiar. Anne Boleyn was a child of this Thomas Howard’s sister, Lady Elizabeth, while his brother, Lord Edmund, was Katherine Howard’s father. This family, with its origins in rural Suffolk, had certainly come a very long way in a relatively short time!

However, the price the Howards were to pay for power, fame and fortune under the Tudors was great indeed, including the executions of the queens Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard and their cousin Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, an arrogant young man who had looked down on the “new erected men” at Henry VIII’s court with such disdain, conveniently forgetting the more humble side of his own family history. His father, the third Duke of Norfolk, escaped beheading only because Henry VIII died the day before it could be carried out, but was to remain in the Tower for the whole of the six year reign of Edward VI, and was only released when Mary Tudor came to the throne in 1553.

But that was not the end of it: Henry, Earl of Surrey having been lost to the headsman, it was his son, another Thomas, who succeeded as fourth duke, but he was executed in 1572 by Queen Elizabeth I (a Howard through her mother, Anne Boleyn) for his involvement in plots to replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots, whom he had hoped to marry.

These were dangerous times for anybody still adhering to the ‘old’ religion (the Howards of today are still leading Roman Catholics) but especially for such a prominent family so close to the throne, and the fourth duke’s son Philip, Earl of Arundel was a prisoner in the Tower for ten years. Nobody took the trouble to inform him that the charges against him had not been proved, or that Queen Elizabeth, his second cousin once removed, had never signed his death warrant, so he lived every day in fear of the executioner knocking at the door. He died in 1595, still a prisoner, at the age of 38, possibly of dysentery. Philip Howard was canonised by the Roman Catholic Church in 1970.

Lady Anne Mowbray – the High and Excellent Princess is a short book concentrating solely on Anne, and tracing the little girl’s story from her eagerly anticipated birth in December 1472 to the present day. It includes the demise of the Mowbray dukedom of Norfolk when her father, whose only child she was, died young without a male heir; her marriage as a five-year-old to the four-year-old boy known to history as the younger of the Princes in the Tower; her own death at the age of eight and the eventual settlement of the Mowbray inheritance on her rightful heirs, the Berkeleys and Howards, by Richard III, her uncle-by-marriage, who had escorted her at her wedding. Also examined are the reasons for her having been interred three times, the discovery of her remains on a bomb site and the twentieth-century experts’ struggle to prepare her bones for decent reburial within the almost impossible time limit set down, somewhat reluctantly, by the then Home Secretary.

Marilyn’s book can be ordered at www.queens-haven.co.uk/queens-haven-orders.htm

Notes and Sources

- All references in this article: The Mowbray Legacy; Lady Anne Mowbray – the High and Excellent Princess

- Elizabeth Tilney died before her husband had the dukedom restored. He almost immediately married her young cousin Agnes Tilney who became Duchess of Norfolk in 1514. In her old age Agnes was committed to the Tower in 1541 for having withheld information about her step-granddaughter Katherine’s behaviour before her marriage to Henry VIII.

- For the (sometimes supposed) connection with the image of Elizabeth Talbot and the Ugly Duchess in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland see www.queens-haven.co.uk/the-ladies-on-the-mowbray-cover.htm.