Following on from last week’s episode “Ruling by the Book”, Dr Janina Ramirez looked at the use of illuminated manuscripts by medieval kings. Here is a precis from my notes…

Dr Janina Ramirez set the scene by explaining how in the 1420s the treasures of the French royal family, the nation’s culture and history, were stolen by the English. It was not a loot of gold and jewels but a cargo of manuscripts, the French royal family’s collection of illuminated manuscripts. She then looked at The Grandes Chroniques de France, an illuminated manuscript of over 400 beautiful images detailing the great deeds of the French kings and showing what a king should be – a lawmaker, arbiter and warrior. It was compared to an English one which also had strong depictions of kings and illustrations of King Arthur with Excalibur, Richard the Lionheart with Excalibur, then Edward I… However, the last entry was very different. The usual official praise for the King had been scrubbed out and in its place were abject words:-

“I am called the tumbledown king and all the world mocks me…”

The words of Edward II who was deposed and imprisoned in Berkeley Castle. It is not clear whether these words were in fact written by Edward or whether they were propaganda but they show the crisis in England caused by Roger Mortimer, Queen Isabella’s lover, hijacking the country and the uncertain future of Edward III.

Ramirez went on to discuss the book given to the 14 year old prince (the future Edward III) to prepare him for kingship, “A Mirror for Princes”. It contained everything that a prince needed to know: knowledge, virtue, the chivalric traditions, how to govern etc. Ramirez saw it as a living document because it was not finished and it included early images of a cannon and archers, weapons that the King would later use to his advantage. The book also had a dark side, it included the arms of Edward’s uncles and his mother, Isabella, who had all joined with Mortimer to remove Edward’s father from power. It was a warning to the young Edward III.

Professor Ian Mortimer spoke to Ramirez about the new vision of kingship at that time and how a good medieval king had to be a lawgiver, fair to his men, strong militarily and in control. Edward III was strong and he and his band of trusted knights captured Roger Mortimer and executed him.

Ramirez then stood in front of the round table at Winchester and spoke of how Edward III could relate to King Arthur and his model of kingship. The symbolism of the round table with the wise king at the head and the nobles round him, without precedence, was important to Edward after the chaos of his father’s reign and he made the symbol a reality by organising jousting, feasting and tournaments to keep his noblemen around him. The victory over the Scots at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333 and the continued peace at home showed that this model was working.

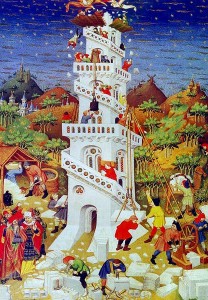

Ramirez then spoke of how the French king died childless and the new Valois line were very aware of how Edward had a claim to the French throne through his mother, Isabella of France. Jean de Valois was responsible for a beautiful manuscript, one of the most heavily illustrated manuscripts of the 14th century, which aimed to show the legitimacy of the Valois claim and was a powerful piece of PR. However, Edward III saw his claim as legitimate too and a dispute over land in Gascony on 1337 gave him the opportunity to put foward his claim. In 1346 Edward sailed from Portchester Castle to Normandy to challenge the French king and the English army left a trail of destruction in their wake. At the Battle of Crécy England defeated France through the use of cannons and longbows. Professor Ian Mortimer explained how England won in a calculated fashion by using projectile weaponry. It had taken five years to make the 3 million arrows used by the English army (the reason for the delay between the land dispute and England setting out for France) but Edward showed that a small but well equipped army could take on a much larger army by using cannons and long bows. This victory meant that Edward was still be talked about as the greatest King of England hundreds of years later.

Ramirez then spoke of how the King’s nobles emulated their king by commissioning illuminated manuscripts about the Arthurian legends. She spoke of one in particular, one commissioned by Humphrey de Bohun, which had as its frontispiece an illustration of the De Bohun coat of arms and that of the King, to show the family’s closeness to the King. Later, it had an illustration of King Arthur with Guinevere and Lancelot whispering in the background and Ramirex explained how, of course, Lancelot’s betrayal, his affair with Guinevere, led to the collapse of the round table so perhaps this was suggesting that the power of a king could be tempered and that the King’s noblemen were being detractors through their manuscripts.

During Edward III’s reign, the Black Death swept through Europe, bringing an Apocalyptic mood, yet there are no reference to the disease in the royal manuscripts. While London was overflowing with dead people in 1349, Edward III set up a new chivarlic order on St George’s Day, the Order of the Garter. It was made up of the King and 25 members, knights the King had fought alongside with at Crécy. The illustration of the King with the warrior saint suggested that the King had been invested with almost religious authority and it acted as propaganda, the message being that the King was in complete control and despited the disease ravaging the country it was ‘business as usual’. Ramirez pointed out that the arms of England quartered with France and the motto of the order, “Honi soit qui mal y pense”, spoke of Edward’s claim to France and that the garter belt was actually the small leather strap which was used to join armour by the Knights at Crécy. Ramirez stated that it was “a master stroke of image making” and that Edward was saying that his kingship was one of “religious integrity” and “Christian orthodoxy”.

Another interesting book featured in the programme was the “Omne Bonum” encyclopaedia which was written by one of Edward III’s clerks and which contained over 1350 entries, all ordered alphabetically for the first time. This book showed the secularisation of manuscripts, the idea that illuminated manuscripts were not just for royalty and religious houses.

Ramirez then went back to the De Bohun family and spoke of how, at Pleshey Castle, the family employed scribes from monasteries and secular artists to produce illuminated manuscripts. She mentioned that the crucial ingredient in illuminated manuscript making was gold and illuminator Patricia Lovett demonstrated how illustrations were made. She explained that the illustrator needed to know exactly where the gold was going to go from the start and that gesso was applied with a quil, heated by breathing on it (to make it sticky) and then gold leaf was added. Further colours were then added to the illustration, along with the outlines. Ramirez then went to talk of the Book of Hours produced at Pleshey Castle sometime in the 1370s which featured a fidelity story from the first Book of Kings with the illustrations speaking of the family’s loyalty to the King. Sir Humphrey de Bohun was suspected of poisoning the Earl of Warwick and so was out of favour with the King at this time and therefore vulnerable. His estates were targeted and Ramirez explained that it was rumoured that Edward had Sir Humphrey secretly hanged. The De Bohun dynasty was destroyed and De Bohun’s youngest daughter, Mary, was taken from a convent and forced to marry. Interestingly, her son became the great warrior king, Henry V.

Ramirez then went on to discuss Thomas Hoccleve’s “The Regiment of Princes”, a manual used by the Prince of Wales (the future Henry V) who stood in for his father in 1410 when Henry IV was ill. This book emphasised the Cardinal Virtues – prudence, justice, courage and temperance – and was written in English. By writing in English, Hoccleve was stressing the Englishness of the young prince, the fact that all his grandparents were English. This really was a key stage in English history and showed the break with France. Ramirex went on to talk of how Henry V’s victory over the French at Agincourt resulted in the English occupation of half of France and the stealing of the French royal family’s collection of manuscripts from the Palace of the Louvre by John, Duke of Bedford. These incredible gold bordered manuscripts were France’s treasures.

Ramirez examined the “Bedford Hours”, an illuminated manuscript given to the future Henry VI by his aunt, Anne of Burgundy, and his uncle, John, Duke of Bedford. It had been adapted from a French manuscript, probably a manual for a French prince, and featured full page illuminations from the Book of Genesis, scenes that a Christian prince should have easily recognised, as well as featuring an illustration of the Duke of Bedford kneeling before England’s warrior saint, St George. Ramirez spoke of how the book captured the aspirations of the whole English nation for the prince who would soon be crowned king. Henry VI was to be a failure though and was never to show any of the cardinal virtues. He never fought France and the English conquest unravelled as a result of his reign. The book, however, is interesting in that the illustrations of people like the Duke are real, rather than symbolic.

The final book that Ramirez examined was The Shrewsbury Book, an illuminated manuscript presented to Margaret of Anjou, Henry VI’s bride-to-be, by John Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury. It featured a powerful image showing all of hnery VI’s claims to the French throne and showing the French and English royal dynasties as having a common ancestor: St Louis. This elaborate fantasy, however, did not match the reality of Henry VI’s reign and France began reclaiming English lands such as Normandy and Gascony.

The programme concluded with the idea that in medieval times the institution of kingship had to keep re-inventing itself and that royalty was now “defined by majesty as much as divinity” as books became more and more elaborate.

If you’re in the UK, you can catch up with this episode of Illuminations: The Private Lives of Kings with BBC iPlayer, see http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b019h3g2. If you’re in London between now and the 13th March make sure you go to the British Library’s special exhibition Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination – see Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination for more information and lots of beautiful images. There is also a book available at that link.

Many of the illuminated manuscripts can be seen on the British Library website by browsing their Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/welcome.htm

Excellent article! Thank you so much for sharing that information–it’s so interesting that these books almost catalogue the development of the idea of kingship and what it means. These high ideals I do think had big impact on Henry VIII–he really did wish to be a virtuous king, especially in the idealism of youth when Wolsey was doing much of the actual work of government. But once Henry had the reins himself, he didn’t exactly live up to those ideals, did he? I love these manuscripts and will check out the link to see them online. Thanks again!

Interesting – a kind of “Kingship for Dummies.”

Excellent summary Claire. Thanks a lot.

John Duke of Bedford and his brother Humphrey Duke of Gloucester (mentioned in passing during the programme) are very interesting people. As brothers of Henry V, each of them played a leading role in the government of the country during the reign of the young Henry VI. I didn’t know that John had plundered the French royal library but I was well aware the Humphrey founded the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The oldest and most atmospheric part of the Bodleian is still called the Duke Humphrey(although the main library takes its name from the later benefactor Sir Thomas Bodley).

So both men were very cultured and appreciative of books and understood their value. What a shame that Henry VI proved so incapable of benefitting from their influence.

They had one other thing in common – both had wives reputed to be witches!

Very informative. Thank u Dr Ramirez