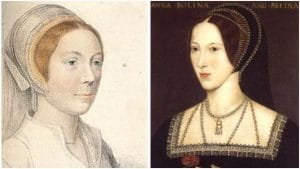

Thank you to Clare Cherry for writing this guest article for us today. I know Clare is very concerned about how some theories and myths crop up so regularly that they are taken as facts, and yet many of them have very little basis. Goodness knows how many times I’ve had to correct the idea that Anne Boleyn was charged with witchcraft, for example.

Thank you to Clare Cherry for writing this guest article for us today. I know Clare is very concerned about how some theories and myths crop up so regularly that they are taken as facts, and yet many of them have very little basis. Goodness knows how many times I’ve had to correct the idea that Anne Boleyn was charged with witchcraft, for example.

Over to Clare…

There are hundreds of books about Henry VIII and his wives, particularly about Anne Boleyn, and to make a splash, there is a constant desire to come up with a new ‘fact/theory’ to make the story fresh and ‘different’. I’ve read a number of books in the past thirty years which desperately try to come up with a different slant on the lives of Henry and his wives, but I can’t help feeling that this sometimes comes at the expense of history and historical accuracy, when vague theories are later regurgitated as fact.

We’ve had the ‘sexual heresy’ theory where Anne’s last miscarriage, when she supposedly gave birth to a deformed foetus, caused her downfall. The only person who ever mentioned the miscarried foetus of 1536 being deformed was Nicholas Sander writing in exile during the reign of Elizabeth I. It wasn’t mentioned at the time of the miscarriage or at the subsequent trial of Anne for sexual offences. But despite there being no corroborative evidence whatsoever, a whole book has been dedicated to the theory, and George Boleyn has been turned into a homosexual man whose lover was Mark Smeaton because they once shared a book and because George Cavendish wrote about George’s ‘unlawful lechery’, despite the fact he also wrote about Henry VIII’s unlawful lechery. Does it all just stem from the need to come up with something different in order to be heard?

Perhaps the ‘sexual heresy’ theory is nothing more than that and doesn’t pretend to be anything other than an academic ‘what-if’. But if a theory has no basis to it, if it’s merely put forward as an interesting academic debate, then what’s the point of it? Is it clever, something to be respected and admired? Anyone, whether they are a historian or not, can come up with any theory on any subject. Questioning, challenging and re-evaluating historical sources is very different to coming up with a theory and trying to make the evidence fit it.

Over recent years it has been suggested that Catherine Howard was sexually abused by Francis Dereham. Yet they had sex on numerous occasions in a room full of other girls with no suggestion that this was not consensual. The fact that a terrified Catherine later accused him of rape to save herself doesn’t make it true. It is also said that Catherine was being blackmailed by Culpeper, who had found out about her relationship with Dereham. There is zero evidence for this. Gareth Russell in his new biography of Catherine brilliantly dismisses these theories. But again, do they stem from trying to write something different? The rehabilitation of Catherine, which is admirable, has had to come at the expense of the men around her by making them rapists and blackmailers. It’s a theory which is rapidly gaining momentum and is on it’s way to becoming fact.

We have now got Anne Boleyn in love with Henry Norris; a theory which presumably stemmed from a desire to find a new slant on their story. The theory goes that Anne didn’t offend the King with her body, but she did with her mind and heart because she secretly loved another man. Of course, she could have been in love with Norris, but to interpret her denial of the offences against her as compelling evidence of this seems a bit of a stretch. It is just a theory, but after it’s repeated often enough, how long before some people start thinking it as fact? After all, in fiction Anne and George have been shown to commit incest to pass their child off as Henry’s. It didn’t take long before social media confused that with fact, and people started stating it as such.

On her author website, Alison Weir says of Anne Boleyn:

“Indeed, the Anne who appeared on the scaffold, displaying great courage and dignity in the face of death, hardly seems to be the same woman who, years before, had schemed and plotted to achieve the throne, and who would not have stopped at murder had she had the opportunity. Had Anne not met the end she did, she would no doubt have gone down in history as a figure of infamy, with few good points to redeem her reputation, and which is certainly the way in which the majority of her husband’s subjects viewed her. But instead, the succeeding centuries have enveloped her name in romantic legend, so that within a very short time she came to be known as a wronged wife, whose wicked husband murdered her in order to marry her lady-in-waiting.

This is obviously a much-distorted picture. If Anne had had her way both Catherine of Aragon and her daughter would have gone to the block: so much is clear in contemporary records and letters. But because Henry VIII would not consent to this ultimate atrocity, Anne had to content herself with a campaign of persecution as relentless as it was cruel. This is all conveniently forgotten by historians who allow themselves to be carried away by the harrowing descriptions of Anne’s last days, and the remembrance that she left behind her a daughter not yet three.”

This clearly shows Weir’s views on Anne, so it’s hardly surprising how she depicts Anne in her fiction as well as her non-fiction. It doesn’t say anything about Anne fleeing to Hever to try and remove herself from Henry’s attentions. Instead, Anne is the schemer depicted in fiction who plotted to achieve the throne. Does anyone really believe that Anne was solely responsible for the treatment of Catherine and Mary, or that she seriously sought their deaths? But this does go a long way towards how Anne is viewed in certain quarters. Again, maybe Anne was everything Weir believes her to be. A plotter, murderess, poisoner etc. It’s possible, but again, there’s no proof that she and her family plotted to kill Fisher or Catherine. Accusations are not evidence; they are just accusations.

Historian G W Bernard had a hunch Anne was guilty of at least some of the crimes levelled against her. He devoted a whole book to that hunch, primarily using the contents of a poem written by someone not present at the trials. Alison Weir believes Anne was a scheming potential murderess who was corrupted at the French court, whose mother had a bad reputation, whose brother was a rapist and whose father pimped her to the King for personal gain. Retha Warnicke thinks Anne gave birth to a monster and was surrounded by a circle of homosexual men. To accept these views is to overlook all of the evidence to the contrary and to simply conclude, ‘it’s possible’.

Of course, it’s possible that Anne did give birth to a grotesquely deformed foetus in 1536. It’s possible that George Boleyn was having a relationship with Mark Smeaton. It’s possible Catherine Howard was raped by Francis Dereham and was being blackmailed by Thomas Culpeper. It is possible Anne Boleyn was guilty of all the charges levelled against her. It’s possible the Boleyn family did poison Fisher. It’s possible they did poison Catherine of Aragon. It’s possible Jane Boleyn did hate her husband and that she did plant seeds to have him accused of incest and treason. It’s all possible because anything is possible, but it doesn’t make it probable, or even in some cases logical.

Quite often a random idea can blossom into a theory based on a possibility. That possibility can become so ingrained that the person putting forward the theory starts thinking of it as fact. The difficulty with that is that extant sources can become distorted in order to try and prove it.

For instance, a lot of the ‘evidence’ to show that Jane Boleyn accused her husband and sister-in-law of incest is fabricated and has been debunked. The only eye witness account of her execution makes no mention of her confessing to lying about them. But if you really want to believe she was the informer then you are going to take that myth as fact, whether you know it to be misleading or not. No one at the trials, or who wrote about them immediately afterwards, made any mention of Jane – other than the note given to her husband, George, regarding Anne confiding in Jane about Henry’s sexual dysfunction – and to suggest otherwise is disingenuous.

A lot of accusations against people who lived so long ago, and a lot of the theories about them, are put forward based on the adage, ‘you can’t prove a negative’. I think that is a particularly irrational adage to base a belief on; after all, if we followed that to the letter then all of the Salem witches were in fact witches, as is anyone accused of witchcraft. Everyone who ever spent any time together, just the two of them, must have been having sex. If you do not have an alibi for a crime, then you are guilty. No civilised legal system convicts people who can’t prove a negative, so why are we prepared to accept a theory based on it, or based on the assertion that anything is possible. Isn’t that a ridiculous argument? We could theorise that Henry VIII was having an affair with Henry Norris because they spent time alone together in intimate circumstances. After all, it’s possible, and there is no evidence to prove they were not having a sexual relationship. We could go on and on and on.

No one should ever stop questioning what was previously thought to be incontrovertible. Look at Darwin, Wallace, Columbus, etc. In the world of history, there are people who work hard to dispel long established myths, only to have more myths grow out of nothing more than someone’s vague hunch. Is it clever, enterprising and deserving of respect to hide behind the fact that it is impossible to prove a negative and that anything is possible? We deserve to have theories justified by the people putting them forward, with sound evidence, and if they can’t justify them then aren’t they just fictional devices masquerading as something supposedly more noble?

Clare Cherry works as a solicitor in Dorset, but has a passion for Tudor history and began researching the life of George Boleyn in 2006. Clare started corresponding with Claire Ridgway in late 2009, after meeting through The Anne Boleyn Files website, and the two Tudor enthusiasts became firm friends. In 2014, Clare and Claire published George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat, a biography of George Boleyn.