Following on from yesterday’s article The mummy on the building site and on the anniversary of the finding of her remains on 11th December 1964, Marilyn Roberts discusses who Lady Anne Mowbray actually was.

In January 1476, John Mowbray, fourth duke of Norfolk, died suddenly aged 31 at his great castle in Framlingham in Suffolk. Apart from the loss of a husband, father and the head of a great medieval noble dynasty, he having left only one child, and a daughter at that, meant the predicament for his family was just about as bad as it could be. Three-year-old Lady Anne, being a female, was not allowed to hold a dukedom in her own right, and had to take the lesser title of Countess of Norfolk, and, being still a minor, became the ward of King Edward IV.

Usually in such circumstances the monarch would farm out the guardianship of a minor to the highest bidder, who would benefit enormously from the incomes from the ward’s lands and properties during his or her minority. King Edward, though, already had something of a shady reputation of seizing the main chance himself, and lost no time in securing Lady Anne’s betrothal to his son, Prince Richard, Duke of York, younger brother of Prince Edward, the future Edward V, and made the boy Duke of Norfolk in a new creation of the old Mowbray title. Betrothal at so young an age was by no means unusual, but as soon as he was able, the King named the day for what was to be a full and binding marriage ceremony. The wedding took place amid the greatest pomp and splendour imaginable on 15 January in 1478 at St Stephen’s Chapel in the Palace of Westminster, the crypt of which survived the fire that destroyed most of the old Westminster Palace in 1834 and is still in use today. The bride was five years-and-five-weeks old and the groom four-and-a-half.

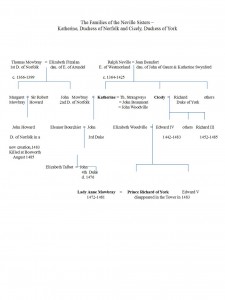

The poor children had to endure hours of mind-numbing ritual that would mean nothing at all to them, until at last Anne was led out in grand procession with the Dukes of Gloucester on her right and Buckingham on her left. Gloucester, then aged twenty-five, his rich outfit carefully chosen and arranged to camouflage the scoliosis we now know he suffered from, was uncle of the bridegroom and was also the bride’s first cousin-twice-removed. Cicely Neville, mother of Edward IV and the Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III) and so grandmother of the groom, was a sister of Anne’s great-grandmother, the Dowager Duchess Katherine Neville, widow of John Mowbray, second Duke of Norfolk. In fact, in St Stephen’s Chapel there had been the rigmarole, purely for show, whereby a clergyman dramatically held up the proceedings by barring Anne’s way, claiming the marriage ought not to take place between the prince and ‘that High and Excellent Princess’ because of ‘nearness of blood’. How convenient, then, that another duly brandished a dispensation from the pope allowing the union to proceed, a document that had actually been in the possession of the king and clergy for several months.

(Click on family tree image to make it bigger)

Although the magnificence of the garments and surroundings was overwhelming, the crush of nobility and royal persons at the wedding feast was so great and uncomfortable that the herald recording events complained he was unable to see properly what was going on. He noted the rather low-profile presence of a young man by the name of Henry Tudor, seated at one of the less prominent banqueting tables. However, we have to wonder whether he could have been mistaken, bearing in mind the enmities of the wars of the roses were still simmering and young Henry, then aged 20, had seen fit to stay in exile in Brittany with his uncle Jasper and wait for better times. Little did Henry know those better times, for him at least, were less than a decade away.

One person who definitely did make an appearance was Anne Mowbray’s attractive new sister-in-law, Princess Elizabeth of York, the girl destined almost nine years to the day to become Henry Tudor’s bride, and in 1491 mother of the future Henry VIII. The day after the wedding the reason for moving matters along so quickly became abundantly clear when parliament passed legislation allowing the new husband to keep the Mowbray fortune for his lifetime should Anne die childless, which was most irregular.

At her marriage Anne Mowbray, now Duchess of York and Norfolk, was referred to as ‘the high and excellent princess’ which would have been entirely appropriate for one who, although still a little child, was the second lady in the land after the queen, Elizabeth Woodville. It is thought Anne went to live in her mother-in-law’s household, but nothing is known of her life as a royal princess except that she died at Greenwich Palace in November 1481 just short of her ninth birthday. (The cause of death is unknown, but examining her remains in 1965, Dr. Roger Warwick, Professor of Anatomy at Guy’s Hospital Medical School in London, found no evidence of skeletal injury or disease and concluded that Anne Mowbray was a well-formed, relatively healthy little girl who had escaped fractures and perhaps most infections of childhood.) Her anthropoidal lead coffin was taken by river from Greenwich to Westminster on a barge decked out in the most expensive black material, for her burial with great solemnity and enormous expense in the relatively new St Erasmus Chapel in Westminster Abbey, which had been commissioned by her mother-in-law.

Within a few years the fortunes of the House of York were toppled following the early death of Edward IV in April 1483 and his sons aged 10 and 12 disinherited by their uncle Richard and not seen again after September 1483. It was at this point that Anne Mowbray’s fortune that had been appropriated by her father-in-law was restored by Richard III to her rightful heirs, Lord William Berkeley and Lord John Howard.

Before the end of the decade in which her only child had died, church records show that Anne’s widowed mother spent part of her time living at ‘the great house within the close’ at the abbey of the Poor Clares, sometimes called the Minoresses, north of the Tower of London. Later on she is found to be sharing the accommodation with widowed friends and relatives, which points to the place having acted like a kind of medieval rest home for the nobility, and it was here she ended her days in relative poverty.

This building now covers a large portion of the site of the Abbey of the Minoresses, or Poor Clares, including ‘the great house within the close’, where Anne’s mother lived out her later years .

In 1502 Henry Tudor, or King Henry VII since his victory over Richard III in 1485, decided to build a new chapel at the east end of Westminster Abbey, which meant the demolition of the St Erasmus chapel. Obviously burials were going to be disturbed and Anne, Duchess of York and Norfolk was among those affected. In her case the decision of where to find a suitable temporary home for the coffin was not too difficult, as her mother was already living in a religious establishment two miles away. The Dowager Duchess made her will days before her own death in 1506 and gave instructions for her burial in the Minoresses’abbey church near close friends who had predeceased her. She made no mention of proximity to her daughter, so there must have been every expectation that Anne would be returned to Westminster Abbey eventually, and why this never happened when the Lady Chapel was completed is not known: perhaps the young Henry VIII, who succeeded his father in 1509, simply wanted memories of the past to be erased and Anne was conveniently overlooked.

Henry VII’s Lady Chapel, an extension to the east end of Westminster Abbey begun in 1502. In May 1965 Anne Mowbray was reburied on the first bay on the left, on the curve of the building; the urn containing remains purported to be those of her husband and his brother lies near Queen Elizabeth I in the area above the blue car.

Could Anne Mowbray ever have been queen? Given that she was the wife of the younger son of Edward IV and taking into account the high mortality rates of the times, it was not impossible, but it would have happened only upon the death of her young brother-in-law and his father before Anne’s own death in 1481. What is an interesting thought, though, is that in such circumstances the children would have become King Richard III and Queen Anne, whereas the Richard III and Queen Anne who did come to the throne in 1483 were, as we know, two entirely different people.

Notes and Sources

Lady Anne Mowbray – The High and Excellent Princess by Marilyn Roberts and The Mowbray Legacy by Marilyn Roberts. Both books are available from Queens-Haven Publications – www.queens-haven.co.uk, email info@queens-haven.co.uk.

Framingham Castle photo – This image was originally posted to Flickr by Squeezyboy at http://flickr.com/photos/60052279@N00/41401746. It was reviewed on 25 July 2008 by the FlickreviewR robot and was confirmed to be licensed under the terms of the cc-by-2.0. wiki commons.