Thank you to author and historical researcher Amanda Harvey Purse for sharing this Boleyn-related article with us today. Over to Amanda…

Thank you to author and historical researcher Amanda Harvey Purse for sharing this Boleyn-related article with us today. Over to Amanda…

It is true to say that over the years of studying the history of art, my love for Leonardo da Vinci’s work has outshone my love for many other artists. As da Vinci was not his surname, but the place in which he was born, out of respect, I will be calling the great artist by his first name within this article. Although I have just called him a great artist, Leonardo was a true Renaissance man for the Medieval and Tudor period. Being only five years older than Henry VII, Leonardo lived through times of war and unrest too, while becoming a master of most trades as he made discoveries in civil engineering, anatomy, geology and hydrodynamics as well as many other subjects; however, it is perhaps when Leonardo turned his hand to paint, that he became a household name from the Tudor period until now.

It may well be hard to imagine Leonardo within the same period as King Henry VII and his son, much like when we think of Westerns films or Sitting Bull and Colonel Custer living at the same time as the Industrial Revolution and Queen Victoria, something may seem to jar a little with these thoughts with us at first; however, Leonardo was indeed a part of the Tudor period, painting his way through the cities of Milan, Florence, Rome and Paris, to name but a few.

Although much of his artwork interests me, two pieces stand out a little more than the rest. These are not the most known of his works – in this modern day, it will not be so easy to find these works on a magnet or novelty mobile phone cover, for example. However, to me, these paintings have the ability to enchant, all the same. These are La Belle Ferronnière and Lady with an Ermine, the latter being a lady holding a white stoat and it has been suggested that the model for this painting was the mistress of Leonardo’s employer, Ludovico Sforza.

To try to understand why the latter painting interests me, I researched it. One of the many things I like about Leonardo’s work is all the suggested codes and symbols he has been said to have added to his artwork, a popular activity for the time, as many portraits of the Tudor monarchs also show us. The Lady with an Ermine is no exception, as the white stoat, for example, was a symbol of purity because it was said that the animal would rather face death than soil its clean, white coat. Was Leonardo suggesting that the model was actually to him a symbol of innocence? We will probably never know his true intention; however, the question of it, the debate of it, fascinates me.

I believe this painting fascinates me for two other reasons. The first is that the model does not look straight ahead at the viewer, nor does she look sideways on. The model, uniquely, is turned in such a way that she appears to be rotating to a third, invisible person in the room. I have always wondered who this person could have been. The second reason is that, if you look closely at the painting, you can see where Leonardo used his fingers to blend paints to have his art the way he wanted it. In fact, when testing was done in later years, Leonardo’s fingerprints could be clearly seen in certain areas. A piece of the great artist, left in the paint for all time, for us future generations to see. I don’t know if many would agree with me, but I think there is something uniquely special in that.

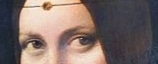

However, it is the other painting I mentioned at the beginning of this piece that I wish to focus on for this article. La Belle Ferronnière is an interesting painting, if often underrated. It may not have the fame of the Mona Lisa or The Last Supper, but still, she captivates anyone that is lucky enough to see her in person, or even when they come across her in a book – that is the power this woman holds.

I do not think I am the only one to feel this way, because in the 2006 Columbia Pictures film The Da Vinci Code, the beginning scenes show the Paris Louvre curator running through the museum as he plans how to leave clues for the main character. As he does this, we, as the viewer, are given flashing images of artwork that the Louvre owns. The flashes focus on the faces within these paintings, to make it look as if they are also witnessing this event with us. One of the pieces of art that flashes up is La Belle Ferronnière and perhaps, more importantly, the camera focuses on her eyes.

I do see what the film was trying to portray in this one moment, a film that mainly and famously concentrates on the Mona Lisa to represent its story, still has a moment for La Belle Ferronnière. Could this suggest that although the Mona Lisa is agreeable, that she is powerful, – she certainly looks at you from any corner of the room she is placed in within the Louvre – but that Leonardo’s brilliance was not confined to just one piece of art, that it is in every piece? The film’s focus on her eyes certainly mirrors the fondness I have for her eyes. For years, I have tried to understand why this painting makes me stop in my tracks to look at her. I have tried to find out why I am always in awe whenever I see it. Was it simply because it was painted in the 15th century by Leonardo? Or was it something more than that?

I had thought once that it might be the mystery this piece holds. For one thing, it has now been discussed whether this portrait was painted by Leonardo in its entirety, or whether it was a joint project within a studio. Some feel that the model appears to be a little more rigid than other models depicted in Leonardo’s work. Also, the model herself is a mystery. She remains unknown, debated up to this very day, so maybe this painting fascinated me because I wanted to know who she was. So with that in mind, I began researching her, and I was shocked to find that a famous Tudor person had been suggested as the model…

In the 18th century, it was suggested that a record had been made at the Louvre Paris Museum describing this painting. Someone named du Rameau, of the Hotel of the Surintendence, wrote: “This lady is dressed in a red bodice, with sleeves of the same colour, attached with green cords; her hair is dressed short and smooth; her collar is trimmed with a cord; she holds a piece of mesh lace and her forehead is encircled by a black cord with a diamond in the centre.” All very descriptive, but it is in his last few words that we have an identity for the model, for du Rameau wrote that the portrait was of “Anne Boleyn” and he went on to declare it to be in “good condition” (D. R.).

Could this be really be true? Could the famous artist, Leonardo, have once painted Anne Boleyn, a past Queen of England? To get somewhere close to answering this most extraordinary of questions, maybe we should first ask, if it was possible that Leonardo and Anne Boleyn met within their lifetimes?

It is recorded that Anne Boleyn spent seven years at the French court, serving Mary, Queen of France, then Queen Claude, the wife of François I, and perhaps the king’s sister, Marguerite of Angoulême. Seigneur de Brantôme even writes in his Lives of Fair and Gallant Ladies, that Anne was “the fairest and most bewitching of all the lovely dames” while she was at the French court.

In 1515, King François I of France won the Battle of Marignano in Italy as he tried to gain control of Milan. While there, the king was said to have seen Leonardo’s fresco of The Last Supper. Being in awe of this masterpiece, the king was then introduced to the artist and offered him the position of First Painter, Engineer and Architect to the King. Leonardo accepted the position, making his way to France, taking with him many of his works, including the now famous Mona Lisa.

A year later, Leonardo was still within the king’s pay and living at the Manoir of Cloux, near the Château of Amboise. This was previously the residence of the king’s sister, Marguerite, and the king was said to have visited the painter there, while, to repay the friendship, Leonardo was said to have appeared occasionally at the French court. As Leonardo’s time at the French court corresponds to Anne Boleyn’s time there, it has been suggested that Anne Boleyn might have known or, at the very least, have come into contact with the famous Leonardo during her time in France.

So there is a possibility of them having known each other, but did she sit for one of Leonardo’s paintings?

Sadly, it seems as if the answer may well be a ‘no’, or at least no to her being La Belle Ferronnière. Although a previous owner of La Belle Ferronnière in the 1920s believed it to be a painting of Anne Boleyn, and went to great lengths to try and sell it as such – but failing and it leading to a lawsuit – it is thought that the portrait was painted between the years of 1490 and 1496, many years before the suggested birth of Anne Boleyn.

So the sitter of La Belle Ferronnière remains a mystery. However, the way in which she was painted, and the genius behind this lesser-known masterpiece, will no doubt still intrigue us for many more years to come. Whether you want to believe it is Anne Boleyn, or not, this suggestion, this loose connection to the Boleyn family, only adds to the energy this painting holds for me.

Amanda Harvey Purse is the author of the award-winning Martha, Inspector Reid: The Real Ripper Street, The Cutbush Connections: In Flowers, In Blood and In the Ripper Case, Jack and Old Jewry: The City of London Policemen who Hunted the Ripper, the Conan Doyle Estate accepted The Strange Case of Caroline Maxwell, Dead Bodies Do Tell Tales, and Jack the Ripper’s Many Faces.

Studying The Tudors at the University of Roehampton renewed her interest in the period and inspired her to write a book based in the Tudor era. From that, The Boleyns: From the Tudors to the Windsors was born, and will be her first book within the Tudor period. It is due out this year.

As with all of Leonardo’s portraits I am awed when I see it. His depth of realism transports me back to the time it was painted. The connection to Anne Boleyn of this work, even temporarily gives hope that perhaps one day an authenticated portrait of her by a master may yet be found. Let us dream. Excellent article. Thank you.

Leonardo sadly in old age suffered from rheumatism in his hands so he had to lay down his paintbrush and oils, but he has left us many wonderful paintings and sketches, cartoons and designs of inventions that did in hundreds of years time, come to exist, he had the first idea of flight and the hot air balloon, he drew studies of the human anatomy, and his diagram of the baby in the womb and the three dimensional figure which is used in hundreds of textbooks and biology are well known, he was a man far ahead of his time and is even said to have invented the first camera, I too love Leonardo and the queen has some of his sketches in her private collection, it is intriguing to think that the mysterious lady in the portrait could be of Anne Boleyn, but her face is too round and she has a much shorter straighter nose than the many images of her we have seen, that said the sitter is very attractive and she appears to be very young, no more than eighteen I imagine, her eyes are wonderful, a clear grey and they do indeed follow you, Da Vinci was a great draughtsman and in the Mona Lisa her eyes also hold your gaze, in fact all his female subjects seem to have a certain wistfulness about them, the French court was indeed honoured to have his company, Da Vinci it was said challenged the idea of God and that such a deity did not exist, born illegitimate to a poor peasant woman he certainly had a colourful life, he died in the arms of King Francois and is recognised today as the worlds first universal genius.

Firstly thanks, Amanda for this excellent and exciting article.

I love Leonardo de Vinci, he was a genius, a man of immense imagination and creativity. His forward thinking has had historians and engineers baffled for centuries, wondering and experimenting to see if his marvellous machines may have actually worked and to speculate on if any were actually made. I don’t believe Anne Boleyn knew Leonardo de Vinci, although it’s possible she met him in passing or saw him at the Court of Francis I when he visited briefly, like one might spot a famous footballer in the local Tesco.

There is a load of crap written about Anne Boleyn in France and no evidence to support any of it. We don’t know anything about her time in France or what she did there. All we know is she was in the service of Mary, Henry’s sister, then Claude of France, wife of King Francis and she had a first rate education there, the same a man would have, she could speak French and had French manners and was sophisticated because of this. Sorry but that and a few odd bits is it. She isn’t recorded anywhere as is often claimed as being an interpreter for Katherine of Aragon in 1520,_no idea where that notion was invented from, nor did she begin a relationship with Henry Viii or King Francis in France or learn the art of sexual seduction. More likely she learned to keep her virtue and mind her Courtly manners and to be a lady fit for a good marriage as well as to have a career at Court. The last thing Claude of France taught her ladies was the art of seduction. The art of rhetoric, however, to appreciate high art and culture, all of these she would have learned and probably met several artists, including Leonardo, but we have no evidence to support any contact with him. Anne Boleyn wasn’t an important woman during her stay in France, she was one of a number of ladies there finishing their education, possibly a star pupil, possibly a bit more forward or well known because of her father and her sister who is believed to have slept with Francis. (Not as the wh*re she is claimed but maybe once or twice). Anne didn’t become important until she became Henry’s mistress. He hardly noticed her in 1522 at the Pageant at Court in England, he didn’t notice her in the way that he was obsessed with her for another four years. What? Where? When and How? are actually mysterious, although every historian and fan has a theory.

I digress, sorry, Leonardo was famous as a military expert as well as an artist as his time in Milan proved. He designed highly lethal weapons. This was actually quite common because of their attention to detail and imagination. Leonardo may have experimented with some of his own designs at the time he was in service to the Duke of Milan and Cesare Borgia. In England last year his works were on display, his drawings, the famous horse for one, the details, the anatomy, the muscles and tissues were all beautifully detailed and accurate. The Lady with the Ermine is remarkable but it can’t be Anne Boleyn. It is clearly Italian in nature and quite different from the other portraits of Anne that may or may not be of Queen Anne Boleyn. In itself the portrait shows a tall, dark, proud and very elegant lady, eyes which see past you and she seems to know your secrets. If you didn’t know this was over 500 years old one would say it was actually altered with CGI, the portrait is almost three D, almost modern. The lady is haughty and proud, intelligent and a mystery.

The funny thing is, here at our gallery in Liverpool we have a portrait of Margaret of Navarre in our Tudor Gallery at the Walker which was once attributed to Leonardo de Vinci by the man who brought it here in the nineteenth century. It was corrected to being by Jean Clouet and she has a green parrot.

Thanks again for your wonderful article.

I watched a documentary on YouTube a couple of years ago I believe on Leonardo’s inventions. One of the segments was of a group of British soldiers building his ‘tank’ using his drawings. Most people have seen this drawing. It’s turtle shaped with guns all around the outside and had wheels. Anyway they built the propulsion part which was gears and chains either hand or foot powered. Problem was it didn’t work. The gears worked against each other. What the conclusion was is that Leonardo purposely drew it that way so that he would know if somebody stole his idea, kinda like they used to draw fake streets on a map for the same reason. Once the gearing was straightened out the vehicle worked as it should.

That would actually make a lot of sense, few blue prints were produced in those days and one reason may be to protect work and unique skills. Leonardo, building for a military patron may well draw his design ideas wrong, such as his famous turtle, a rotating tank with gunfire. I think Blowing Up History had a go at making these machines by da Vinci and some worked, others didn’t, but the computer models showed they may work. I think some were manipulated around and then could work, but in reality it’s impossible after 500 years to know if a drawing will translate into a working machine. It really is a wonderful mystery and that is what is fascinating about the man. He drew stuff from the 21st century, obviously not all could be used then, he had thoughts, he imagined so some things are just ideas that never came to pass and couldn’t work at that time, may not work even now. His helicopter is too primitive and would never fly for example. He would have kept any working weapons or inventions secret and any drawings would certainly be made with errors just so as they cannot be replicated or his plans stolen.

Did you know that Henry Viii almost came into technology ahead of its time? Again it may not have worked because convex and conclave lenses were not known in 1544, but could Girolamo da Treviso, an artist and military engineer working for Henry Viii at the Siege of Boulogne, where he was killed, have invented the equivalent of a modern huge spy telescope by building a huge magnifying glass which would allow Henry to see the French fleet in Calais? It sounds totally mad and it was never invented but it was something apparently he presented to Henry Viii and the King gave real consideration to. Nobody else believed it was possible and it would have cost more than the war itself so it wasn’t commissioned. Imagine it, the large telescope invented almost a century early. Henry used de Treviso as his engineer to build the tunnels which he exploded the towers in the city of Boulogne in 1544. Another artists talents used for the wrong reasons, but like Leonardo when he worked for the two enemies, Sforsa and Borgia, he needed the money.

I did not know the the story of de Treviso and Henry Viii. That technology could have changed everything for the English.

Have you ever heard of Billy Mitchell? He was real. There was a movie made decades ago with Cary Grant called The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell. After the first world war Mitchell, who was an American flying officer was promoting the use of aircraft in destroying enemy ships. He even had demonstrations using old hulk’s to prove it was possible and could be done. People thought he was nuts. There would never be a reason for such a thing and they were so adamantly opposed to him he was court-martial and drummed out of the service. Twenty years later during WWII every belligerent nation was using aircraft to attack enemy shipping. The Americans in 1942 used planes off of Midway Island to attack and sink the carriers that attacked Pearl Harbor Hawaii a few months earlier so Mitchell was vindicated. My point being history is replete with people who not necessarily could read the future but could see trends far enough ahead to change the future earlier than what actually happened but we only know about a few. Leonardo was certainly one of those who could see possibilities but unfortunately only had 15th/16th century technology to work with.

Yes, Michael, you are right. The Earl of Surrey apparently thought Girolamo was mad as did a lot of people, but if Henry had have had the funds and time to allow him to go ahead and attempt to make an advanced scope or even a weapon, he would now be getting the credit. Henry didn’t believe such people were mad, if he could use them he did. It was in the 1570s that the first long range scopes were used and then the space telescope in the early seventeenth.

The Emperor Rudolph had all kinds of people at his Court who dabbled in the oddest stuff but with the aim of free thinking and scientific advancement and methods.

People like Leonardo and Michelangelo and Archimedes were light years ahead of their time and yes, they could not see into the future, but they certainly could envision it. Archimedes had his claw to pull over ships and may have invented an ancient laser with giant mirrors to zap his enemies ships. The descriptions of the Battle for Syracuse are quite wild. Even if he didn’t have such a weapon it has been shown how giant mirrors work and could have worked even then. The Byzantine Empire invented a terrible weapon of mass destruction called Greek Fire, Napeon, and finally, Archimedes invented a more impressive and practical item, his screw for forcing water uphill.

The story of Billy Mitchell was interesting, thank you, Michael. I had heard of his court martial but didn’t know it was for coming up with the use of aircraft to attack shipping. As you say, the entire thing became the nightmare of reality during World War ii, especially with the terrible events of Pearl Harbour. And yes, it is true, Winston Churchill did know about the forthcoming attack and didn’t warn America, in order to bring them into the War. If it wasn’t for the escorts given to our supply ships and convoys from America from the outset, Britain would not have survived long enough to moan about it. America did a lot for us during the war and we should be a bit more grateful.

The Archimedes screw was an amazing and brilliant invention. We’re still using it. If you look at Leonardo’s rotor on his helicopter design it is that design so he must’ve thought it would work in the air. Augers that we use for digging holes have a bit of that design and if you look at the propellers on ships they’re modified Archimedes screws.

As to Churchill knowing about the attack? I’ve also read that Roosevelt also knew but I’ve never run across anything really credible to verify either claim. I do believe that America entering the war was a good thing however. We got our butts kicked early on but once we found our footing we were quite formidable. I think the biggest advantage to America entering the war was since the mainland was mostly safe we could crank out much more materiel for the war effort than the other allies who were under constant threat of attack. The biggest effect entering the war had on on America was pulling us out of the depression.

I also heard that the intelligence informed Churchill of the intended attack on Pearl Harbour, and the reason he stayed silent was because it would bring America into the war, it maybe true we do not know, but Britain really was on her knees during those bleak days, whatever anyone says about Churchill he did hold this country together in the belief she could survive and beat Hitler, that said about the attack on Pearl Harbour, it really was a low thing to do and says much about the nature of the Japanese than anything else, to choose a Sunday when Christian countries are having a quiet rest, the world was shocked, I know when Singapore fell Churchill was outraged, the trouble was we had an officer in control who was just one of those pen pushers, he was not a military man and so the British army had to surrender, it was something the Japanese did not do and regarded those who did with contempt, they were made prisoners and treated inhumanly through no fault of their own, many died it was an outrage as they violated completely the Geneva convention, some relatives of mine when released after the war suffered stomach troubles all their life, simply because they had been starved and tortured and that was beside the mental trauma they suffered, they say that the atrocities caused by the Japanese during the Second World War is not spoken of in their schools today, just as modern Germany has been trying for decades to put the horrors of the death camps behind them, the evil experiments the nazis did etc, and then there was Josef Stalin, who some say was more cruel than Hitler he had thousands of his own people put to death, his daughter was allowed to live in Britain then after some years she was kicked out, the Second World War did see some superb statesman and the rise and fall of some of the most evil men ever to have lived.

I’m a fan of Winston Churchill ((during WWII not WWI as he was responsible for the disaster at Gallipoli). Did you know, and this should come as no surprise that he wanted to observe the D-Day landings from one of the ships off of the coast of Normandy and had be be talked out of it by his aides? He was a tough old bird and a great wartime leader.Also your King and Queen were quite inspiring choosing to stay in London during the blitz.

Yes I’m not all that knowledgeable about Gallipoli but the king and queen did help to boost morale in London, after Buckingham Palace was hit the queen commented that at last they can look Londoners in the face, Churchill also did his rounds and travelled abroad to meet the armies, it was something Hitler never did and yet it does help to boost morale, it inspired them to see their leader taking the trouble to make quite an arduous journey to see them and talk to them, and yes he was a tough old thing, yet his schooldays were a misery, he was not academically bright and he stuttered, usually caused by nerves, he adored his mother who as you must know, was the wealthy American socialite Jennie Jerome, yet he did not see much of her nor his father, they were distant parents, Winston was mainly in the care of his nannies when home and then packed of to boarding schools when the holidays ended, whilst they indulged in the usual activities of the mega rich and the aristocracy, his father was not very proud of his eldest son but Winston had that in him which were the qualities of great leaders, his speeches were brilliant he was an inspiration not only to Britain but to many around the world, and today his name still commands respect and the triumph of good over evil.

Have you read any of his books? I’ve read The second World War which is six volumes and A History of the English Speaking Peoples which is also multi volume. Because of his writing style they are a ‘quick’ read but even so I had a couple of lighter books going. In my opinion his account is the best and most accurate WWII autobiography out there by a major player. His A History of….. Is well researched and dispassionate and even when talking about his ancestors he pulls no punches. Both excellent works. There are a lot of great people who were poor students. Even Einstein.

No I haven’t read any of his books but maybe one day, it is true what you say however, about those who rise to greatness often struggled at school, it’s the drive the personality the courage that makes a great leader, not if they understand quantum physics and the like.

Absolutely.

Winnie was the sort of cold blooded so and so one needed to lead the country during World War ii. As a young man, he was a hero and his daring escape from prison is well-known. He had a stammer and he felt he wasn’t interested in real academic achievements, although his parents sent him to boarding school, a tough, top school. He was beaten by fellow students and masters alike until his family actually had him taught to box. He took the bullies to task. Randolph Churchill wasn’t impressed by his school reports and made the decision his son would go into the forces. His military career made him into a man and it’s clear he was made by it. His maiden speech in Parliament was apparently brilliant and he outdid his father. Winnie, however, oversaw some of the most controversial political decisions of his time. Here he is unfortunately known for “Gunboats in the Mersey” . In 1911 I believe there was a general strike and unrest across the country. The trouble actually started in Southampton when 25,000 metal, railway and others went on strike. It spread across the country and 80,000 people marched in Liverpool. One Sunday in August some 80,000 to 100,000 people in Sunday best gathered on Saint George’s Plateau to protest. During two weeks that month, several people were shot and killed by police and on this occasion 12_people were seriously hurt, five killed and hundreds had minor injuries. The Government was ordered by Winston Churchill to go in with a heavy hand, several thousand troops were mobilised, causing more riots and now people here gathered to protest in their Sunday best. Gunboats were deployed up the River Mersey and aimed at the City. Now you can’t see Saint George’s from the River so what exactly was he going to do, bombard the City aimlessly? The men women and children there were not rioting and even if they were you can’t blow people up with gun boats. To this day nobody really knows the full orders but obviously the ships didn’t fire. The police went in and people got killed and hurt, but only a minority, thankfully. The tough stance continued for another couple of weeks but the authorities gave up.

Winston Churchill was also notorious for his shoot to kill policy on terror, something which was revived during the 1990s in Ireland. His touch stance on hard crime was actually popular and not out of step with his era. However, one incident during the regular Suffrage Marches which blackened his name was even more notorious. During a March in the Summer of 1912 800 women were set upon and many beaten and sexually abused by his police and more than one woman died. He had ordered heavy handed tactics but when he heard the extent to which his men had gone Churchill was filled with remorse and ordered the arrested women to be released. The papers carried the story and the sympathy was with those arrested and the public were horrified. Churchill was deeply unpopular.

However, during World War Two he led the Coalition Government to victory over Nazi Germany and refused to give in under terrible odds being against us. The German war machine was effective, efficient and merciless. We know this because of the lightening fast blitzkrieg across Europe in the blink of an eye. Churchill had warned the PM, Neville Chamberlain that Hitler was arming for war for years and we should do the same only to be hushed down and the famous Peace in Our Time agreement was a white wash. Churchill was determined never to surrender and he kept our troops going. I can imagine him in a ship on D Day! His visits to the troops, the famous V sign, he was the right man for the job and as such a great wartime PM. I have read his history years ago. The film Young Winston is excellent if you ever get a chance to see him. Two recent films won awards, although I believe one was much better than the other. He has even been in Dr Who. In the end he probably was a great statesman but certainly not the most compassionate of men.

Young Winston is a brilliant film but last time I saw it, they had cut out the end bit where it showed Churchill as a very old man in a dream where his father visited him, it was surreal and very poignant, as it showed Churchill who had always longed for his fathers praise, telling him about the war and of the victory that had been won, Randolph said well done Winston, or something similar, I do hate it when they edit clips in movies, in the seventies they made a series about his mother called obviously ‘Jennie Lady Churchill’ played by Lee Remick, it was wonderful and showed her life in New York and the family’s visit to London, their hasty marriage against the wishes of her father, later on the sad descent of Lord Randolph into the many stages of syphilis, something the men in high society caught easily as they were frequent visitors to brothels, it was a dissolute life which involved drinking gambling and whoring, he had a beautiful very sophisticated wife to, but it was something the aristocracy indulged in, it was a world away from the dinner parties and soirées that was another part of their life, there was even talk at one time of Randolph being suspected of being the ripper, I believe Simon Ward won an Oscar or award for his portrayal of the young reckless Winston, he got his speech of to an art, the film I watched last year was about Churchill to and when he took over from Chamberlain, cannot recall what it was called but the actor was good in that. I saw the Dr.Who one with the Daleks.

What you say just reenforces why I like the WWII Churchill. I love Ian McNiece’s (I don’t know if I spelled that right) portrayal of Churchill on Doctor Who. Seems pretty spot-on. I agree that he is exactly what Britain and the Allies needed during the war. Once they started working together he and Roosevelt made a pretty good team. Just for the sake of argument let’s say Churchill did know the attack on Pearl was coming and said nothing. I’m not so sure that’s the case but even if it was I would not hold that against him. He needed us to get into the war and Roosevelt had no justification to do so.

Sorry for this. My thoughts didn’t come in order!

Though I’ve never seen it Young Winston I was aware of. The movie with Lee Remick as Jennie Churchill I didn’t know existed. I always enjoyed her as an actress and I’ll bet she was well cast. The movie you said you saw last year, was that the one with Gary Oldman called Darkest Hour? It came out in 2018. I didn’t see it but I remember the previews and it looked pretty good. After its release I heard nothing more about it and assumed it bombed.

As an aside I just looked up Lee Remick. She died in 1991 at the age of 55 from kidney cancer.

Yes ‘Jennie’ was a tv series aired here in the seventies, Lee Remick was wonderful as Lady Churchill, there is a bust of her hand in Chartwell, she was quite a girl and married about twice after her first husband died, Lee Remick did sadly die young, I believe she was friends with Marilyn Monroe, a great actress, they have never showed the series again but I’m hoping it will be aired possibly on one of the free view channels.

Yes that’s correct The Darkest Hour, I was racking my brains last night trying to think of it, Oldman was great and he sounded exactly like him, Winston did have quite a distinctive voice and many actors playing him have to get that right, he was a great leader but he could be quite brusque and it’s rather like another hero of Britain in the war, Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, he was it was said of him quite difficult to get along with, bad tempered and critical that said, all the pressure was on these people.

I don’t know about you but I do not care if our leaders are erks as long as they can protect us during wartime. Britain’s General Bernard Montgomery and America’s General George Patton were prima dona’s who could be quite difficult but were merciless on the Germans. Montgomery is known for his battles in North Africa and though Patton also fought and won some battles there he is is known as the commander of American forces in Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge in which the last major offensive by Germany was routed leading to their defeat and surrender a few months later.

I completely agree with you, if they are the right man for the job that’s all that’s important.

Winston Churchill must have been intelligent and academically able because he wrote the History of the English Speaking People which is actually really good and he taught himself history because he didn’t complete his boarding school and wasn’t interested at school. Not that I blame him, I taught myself most of what I know. I had one very good history teacher who fed my interest, one who hadn’t got a clue and one who would put even the most passionate historians to sleep. By the way if anyone is a Jean Plaidy fan as Christine and I are, she had a long debilitating illness after the age of twelve and therefore had little formal schooling. She began reading and developed a passion for history and taught herself. It was a wonderful achievement as her books were always very well researched. Winston was clearly a brilliant politician as well and a thinker. Yes, we did indeed need our leaders to be ruthless during the war. People now really don’t realise who our grandparents were dealing with. Of course the entire German army and people were not Nazis but the Nazis ran the country and the persecution of the Jewish people was the work of the Nazis, but if Germany had won the war, half the population would have been tortured and killed. Hitler was an evil nut and it took tough ruthless men to resist him or the urge to surrender or make peace while he was still alive. He did actually try to get England to back out and come to an arrangement during the war, saying we are all the same Saxon race, but no can do sweetheart. Churchill was the sort of man to take control and dig in when the war was not going well and keep the Government from making decisions that would have given in to a powerful military machine. Remember Hitler was helped to take power by the allies because of how Germany was treated after WWI and the indemnity she had to pay. Hitler might have seized power but he also promised and delivered an economic miracle. He turned Germany into an industrial powerhouse. He made her into an effective and efficient economic country which said stuff you to the enemy and rebuilding brought jobs and infrastructure. The war machine grew out of that highly efficient industry and a hard nosed work ethic did the rest. The evil ideology of Anti Semitic theology was also a rallying and unifying force and those who became Nazis believed the rubbish that Jewish people were not human. That was how these evil creeps justified the murder and extermination of six million Jews and in all eleven millions people including several hundred thousand mentally disabled people. Churchill was uncompromising, he was not going to accommodate anyone and he was ruthless and steady. He was level headed. The people who we were at war with were the most evil people in history: it was only a man like him who could take them on. After the war, Germany was pounded to rubble and this time the European allies made the wise decision to pay to rebuild her, not to punish a defeated people, although the Nazis were punished, because they recognised that was the way to ensure another Hitler didn’t rise from the ashes. Even Churchill saw the wisdom in agreeing to that. Believe it or not, Winston Churchill was the recipient of the Priez de Charlemagne given to leaders and individuals who contributed towards European peace. He received it in 1956. It was in recognition of his efforts to help rebuild Germany and France and foster good relations for the future.

The Germans often refer to the British as cousins, so a friends father told me once, who happened to be German, he came from the Black Forest and made delicious soukraut, it is true we have Anglo Saxon blood in us but other mixtures as well, regarding the occurrences of the war, it was Rudolph Hess who flew here on a secret mission in a bid for peace, he landed in Scotland on the Duke of Hamilton’s estate, it was unexpected and they tried to hush it up, as parliament did not want our allies knowing about it, but Churchill said no way, they were given the ultimatum to withdraw from Poland and they would not therefore we were at war, we made a pact with France, you cannot say you will do this and that then change your mind, you have to stick by what you say else you lose all credibility, Hitler was an enigma, he did pull Germany out of the mire it was in since the defeat she had suffered in the First World War, he was charismatic and passionate about his nation, his speeches inspired his hordes of adoring fans, how is it possible that such a man who promised so much who did a lot of good in his early days of power, could have been the destruction of his own nations fall years later ? He was unstable, watching early films of his speeches shows him raving like a madman, yet he held a nation spellbound, they could not see or maybe chose not to see, the wrong he was doing, he ruthlessly went through the Low Countries and then reached the borders of France, yet still the German people cheered him on, I believe Hitler thought he was another Caesar or Alexander and thought he could rule the world, such people are delusional because that is an impossible task, he made several mistakes in his quest for power, one of them was invading Russia, he reckoned without the long hard Russian winter, his end really was inevitable as he knew he would be put on trial for war crimes and executed, after the war Churchill visited the shell that was Berlin and sat pondering on it all, we can imagine the thoughts that went through his mind, our war leader it is true did write some books, including a biography of his distant ancestor John Duke of Marlborough, Jean Plaidy who had many pseudonyms did suffer ill health as a child yes, have read that, they always tell you a little about the author in the preface, she was born in London and was unable to go to school so she taught herself to read, she did write many wonderful books, some of my favourites are ‘The Murder In The Tower’, ‘The Goldsmiths Wife’, ‘Murder Most Royal’, ‘The Sixth Wife’, and ‘Gay Lord Robert’, they were written in the fifties and sixties, her much later novels seemed to lose a bit of spark, her early novels were under the pen names of Ellalice Tate and Eleanor Burford, she also wrote under the names of Catherine Gaskin Philippa Carr and Victoria Holt, but they are of the Victorian gothic genre, she died somewhere at sea which is a tragedy as her body’s never been found, I love ‘ The Concubine’ by Norah Lofts I never throw my books away either, in fact I have way too many now, I could do with a library.

Just remembered two more old Jean Plaidy favourites ‘Madonna Of The Seven Hills’ and ‘Light On Lucretia‘, these two volumes tell the intriguing and turbulent life of Lucretia Borgia, these really were so exciting and thrilling I could not put them down, some may find them rather heavy going, they certainly are not for those who prefer light reading, but these books I feel was Plaidy at her best, hope you got on ok today Bq.

La belle ferrornniere, the mistress of Ludwig Sforza, called Lucretia Crivella was the lady in waiting to the most educated woman of her day, Beatrice de Este, Duchess of Milan, his wife. She is the Lady with the Ermine in this painting and we know it dates to before 1508 because this was when she died. The two portraits apparently are of the same lady and of course they are by Leonardo de Vinci who was working for the Duke for several years. Unfortunately it is much too early to be Anne Boleyn and isn’t typical of other images of Anne. Anne herself would have been no more than seven when this portrait was made, although she may even not have yet been born as it could be as early as 1496/7 when Beatrice died in child birth.

The problem with portraits and images of Anne Boleyn is that experts will not admit if a proper portrait exists because experts are operating under the false belief that all of her portraits were destroyed and so nothing exists from her lifetime. However, there is no contemporary evidence that Henry had his offensive wife’s portraits all destroyed. Yes, he had her symbols taken down, her heraldic beasts, all of her initials and arms were removed, he refused to use her name or to allow others to speak about her, but there are no orders to destroy all paintings. Henry could have given a verbal instruction but experts have debated as to whether or not remaining images of Anne Boleyn pre date 1536 or not. Now obviously a number date from the seventeenth century or are Elizabethan and we can exclude them. There are others which have produced mixed responses, they could date from between 1550 and 1570 or they need to be reassessed to within the lifetime of Queen Anne Boleyn. A controversial portrait at Nidd Hall caused a sensational debate about three years ago but the sitter is much older and most people believe it to date from the 1570s. A Horenbolt is believed to be a rarely good likeness and similar to one attributed to being of her sister, Mary Boleyn by the same artist. The National Portrait Gallery has a claim on a potential contemporary likeness which has both been dated as contemporary and as Elizabethan. Hever Castle makes a similar claim. However, for me the Ripon Cathedral portrait is a truer likeness.

This portrait was once believed to be the best likeness of Anne Boleyn and to date from 1535. It was even believed at one time to be a gift from the Queen, although Henry and Anne never visited the Cathedral. Henry didn’t go to Yorkshire until 1541 with wife no five, Kathryn Howard. It is very close to her typically rounding features and when we saw it back in 2012_it wasn’t on public display because it was being restored but you could see it by request and see the work on the portrait. Again it is now debated but personally for me it is one of the most striking and authentic images of Anne Boleyn.

Roland Hui backs the National Portrait Gallery Anne Boleyn as authentic dating from 1534 to 1536. He has also worked on articles regarding the 1534 Black Book of the Garter from 1534 which contains an image that may well be Anne Boleyn. This is the official book of the Knights of the Garter and the lady she is acting is Philippa of Hainault the wife of King Edward iii who founded the order. King Henry Viii is shown as Edward iii and himself. The lady is seated on a throne in cloth of gold as if she was being crowned or worshiped and is heavily pregnant, so this is a triumphant portrait. Anne was believed to be heavily pregnant during the first half of 1534 and would have been shown as a triumphant Queen. She would be hoping to be carrying a son and heir. Roland very much backs this image in the Garter Book as an abstract image of Anne Boleyn. Henry Viii was big on the Knights of the Round Table and at this time Anne was in high favour and this imagery was symbolic of the hope her marriage to him was to bring England and of renewal.

Finally we have the famous sketches by Hans Holbein of Anne Boleyn as Queen, in what looks like a fur dressing gown, night gown of black lace, with long sleeves, which Henry gave Anne as a gift, her hair under a cap and not yet the full portrait. It wasn’t unusual for someone, even of high rank to be painted in what we might see as night attire and Anne might have been painted shortly before going into retirement in order to have her baby. In fact it was quite usual as a woman could die in childbirth and her family might wish a commemorative picture of her. If Anne was heavily pregnant, this dress might just have been more comfortable. This was just a preparation for a finished portrait and we do have a finished portrait based on the sketch which may just help us to authenticate it being Anne Boleyn or not. Hans Holbein did a lot of work for Henry and his family, he decorated the cradle which Princess Elizabeth slept in and designed a beautiful wine fountain for Anne as a gift for her husband. This sketch may be the best contender to date.

One final image, which is authentic is that of Anne on the Moost Happi medallion which unfortunately is too damaged by the nose being squashed and in any event such things were not true representations. So unfortunately we still don’t really know what Anne looked like without admitting one of the few portraits possibly from her lifetime is admitted by experts to really be her.

The charcoal sketch by Holbein possibly is the only authentic likeness we have of Anne, like his fellow painter Da Vinci he was an expert draftsman, the one of Anne which surely must be her as it has her name above it, shows her in what must be her night attire as is commonly thought, as she wears a cap on her head and her gown is simple and without ornamentation, she looks downward and she has a jowly chin and her features are similar to those in other portraits of her, she has a long aquiline nose and a full mouth, heavy lidded eyes and heavily marked brows, her jawline is long and narrow, undoubtedly this is Anne and yes she must be pregnant, sketches were made as a preliminary to paintings and yet there are none made of this one, so it is likely this one was of her last and fatal pregnancy, the one which led to her downfall and finally to her tragic death, there is a sketch of Jane Seymour which was the basis for her later painting, this sketch I prefer as in it Jane looks quite pretty, there were hundreds of sketches found in Holbein’s studio after his sudden death from the plague, and we are very lucky the one of Anne is preserved, talking of paintings being commissioned of wealthy and noble ladies when pregnant, brings me to mind of the one of Lady Catherine Carey, this one is not actually definite proof it is of her, yet many writers have this picture in their books and state it is her, this one shows a lady heavily pregnant so yes we can see as death was often sadly the result of childbirth, why these mothers to be had their image captured in oils, the authenticity of early portraits has caused frustration over the years, there was one thought to be of Catherine Howard for many years and in this portrait she is simply dressed with a drab like gown and white collar, she has a downcast gaze and is nothing like the perky look of the young queen in other portraits, the jewellery is simple and she looks rather plain, it is now thought to be that of Elizabeth Seymour, Jane Seymours younger sister, the one found several years ago of Lady Abergavenny caused a furore when found as many art historians theorised it could be a lost painting of Anne, there was one eBay seller who actually claimed it was, the lady’s features were similar to Anne but her face shape was all wrong, she had more of an angular face shape, the portrait by John Hoskins is said to be a strong likeness to Anne and this one I do prefer to others as she has a more softer rounder face, in all Anne’s alleged portraits of her there are similarity in features, they all show a lady with a rather long oval face high cheekbones and heavy lidded dark brown eyes, her complexion is like warm ivory and her hair colouring ranges from chestnut to deep brown, in the Hoskins one and the Hever portrait her hair looks almost black, the NPG one which I have never liked shows her with almost light chestnut hair, this could be because brunettes were not fashionable but she has beautiful eyes, the kind of eyes that it was said cast a spell on all those who beheld her, the Nidd Hall portrait shows her looking rather harsh and old, if this is indeed Anne and she does wear the headdress that is shown on the coin struck during her queen ship, then it is not a flattering one of her, the nose in the coin is damaged as Bq points out, but coins do not show a true likeness anyway, as Eric Ives wrote in all these portraits of her we have the true face of Anne Boleyn, we can ascertain in our mind her true likeness it is not that hard to do, we know she was of medium height and very slender, studies of her skeleton showed her to be of perfect proportions and she was known to be elegant, very slender women with a sense of grace and movement are so described, her hair colouring is not important but she had legendary eyes and in her youth at the French court, was described by Brantome as being the most fairest and bewitching of all the queens ladies, we have enough authentic descriptions of her to conjure up our own image as well as the many alleged or real portraits of her, and of course the Holbein sketch, during her daughters reign when her name began to be exonerated it is said the NPG portrait was painted, and she was spoken of as good Queen Anne the mother of Queen Elizabeth our gods anointed, she was spoken of with sympathy and instead of being the vile woman who destroyed Catholicism in England, began to be hailed as the mother of reform, her reputation which was blackened during the kings lifetime, her name which was never spoken began to enjoy a very real influence in Elizabeth’s lifetime, there is a sense of justice in the way Elizabeth did become Queen, maybe it was Gods way of saying Anne Boleyn was innocent after all?

The Holbien sketch you speak of with Anne in her night cap I believe is authentic. I’ve noticed some publications say the name was added later. One argument for it not being her is that the sitter was sketched so informally. That means nothing. It may have simply been a working drawing of her profile. He would not have necessarily painted what he drew. My mom had an aunt who sometimes did portraits for people and she would have them come in to be sketched in various positions and have them bring in (not wear) the clothes they wanted in the portrait. That was all she needed. Anne may have given Holbienn a bit of time so he could make some working drawings but never completed a portrait because of the events of May 1536.

Some have said they do not believe the sitter in the sketch is Anne but Jane Seymour, but the lady does not resemble Jane who had a much broader face, also profile pictures are deceiving as you cannot see the whole face, many portraits were painted at an angle, there is Anne from Cleves and it is believed Holbein deliberately painted her full faced as from a side view she would not look so flattering, Holbein possibly sketched many drawings of his subjects, maybe it was to determine what work the sitter preferred the best, and that would be the one to paint, Anne was queen for three years and there must have been many portraits done of her, there is said to be a full length one somewhere in a private collection, I have often said it would be lovely had Holbein or another artist of the time painted a rustic scene, both Anne and Henry loved picnics and the surrounding countryside would have looked lovely, accompanied with their beloved dogs and other courtiers and maybe a musician or two.

Thanks for referring to my articles.

In the 1534 Black Book of the Garter, the woman is seen wearing a pendant with the the cipher ‘AR’. This I take it to mean ‘Anna Regina’ – thus Anne Boleyn.

About the Holbein sketch at Windsor Castle (wearing the cap and furred dressing gown), to me it cannot be Anne as the woman is depicted as a blond. The problem, I think, is that few people have seen this sketch in color.

Hi Roland, thanks for your reply. That totally makes perfect sense. I love your work, the whole concept of Tudor iconography and painting, particularly as the painting was beginning to be realistic. I am not an artist, but I married one. He hasn’t done anything for years but he did a wonderful one of Majel Barrett who was nurse Chapel in Star Trek, as a much later character in Deep Space Nine, and she signed it for him when he took it when she came to our Forbidden Planet, years ago. She was really taken with it and held the queue up talking to him. He never really made it in art although he is really good and I keep trying to get him to take it up again, maybe it would be therapeutic. He studied Holbein so he is really keen on the sketches. I love the debate though. The Black Book is beautiful. All that chivaldric symbolism and story telling, the Tudors really did love it. Edward iii of course and his sons were real warriors, although their wars bankrupted the country. Henry Viii thought he was one, but it was only ever really during tournaments. I agree A R definitely Anna Regina.

Wow! Your husband was so lucky! He must be huge ‘Trekkie’.

It’ll be great if the ‘Black Book’ was wholly digitized and put online.

Thanks, yes, we both are. It’s always great to meet one of the stars. The Black Book online would be quite an achievement, as any illuminated manuscript, because they are wonderful works of arts in themselves. It being produced in 1534, is very special as it’s so contemporary with Henry and Anne Boleyn during the better times of their short tempestuous marriage. I believe it also shows a lot about Anne as Queen, the expectation on her to produce an heir and her link to the great consorts of the Medieval past.

You are right, the sitter has very blonde, golden blonde hair to be exact. So could it be Jane Seymour?

It’s amazing how many times I have looked at this, seen it in the flesh at a special exhibition at Windsor, then at Hampton Court and at another house and didn’t notice the sitter has very blonde hair. It goes to show the concept can shift through the title.

Thanks for pointing that out, Roland, it’s actually hard to miss. The other potential Anne Boleyn he painted, there isn’t any hair, but its not certain who its by. Its more the style we have come to know. I can see why the NPG portrait is favourite, though, the French hood was her USP. The Black Book of the Garter being believed to have been painted by Lucus Horenbolt also links us to Anne Boleyn and others, a close connection to the Tudor Court at the time of Henry Viii.

To Christine first: I have a hallwsy closet with boxes full of books, I have bookshelves overflowing with some on the floor in front and the closet where my clotues are has books on the floor. These are about 95% history books. I’m not like this with anything else but I can’t get rid of books. When I’m gone someone else can do it!

Hi BQ. You mention Henry VIII giving the order to eradicate all symbols etc of Anne or he and Anne. That carved cypher of HA survives at Hampton Court. I hang my hopes on that that IF Henry ordered the destruction of portraits of her perhaps one or two have survived and have not been discovered or are misidentified.

I googled Jean Plaidy. I only of her only in passing. Remarkable prolific writer and wrote in so many genres. I also didn’t realize that she died so recently and at such an advanced age.

I only KNEW of her in passing. It was there before I hit send.

Hi yes it’s almost like an addiction, I had many books for years which I gave to charity shops and then I started building up another collection, there mostly all historical biographies and there’s some fiction to, mostly of the historical fiction genre, though i do love ghost stories, every birthday and Christmas I always request more books so ho hum iv got another huge pile, and there littered all over the house, iv loads in my bedroom in my display unit in my lounge, in my dining room, I work in a charity shop for a few afternoons a week and so I often come back with more books, I also love books on stately homes and beautiful gardens, what are often called coffee table books, that is one thing I do find hard to throw away and why should we anyway, they are great for reference, I often read the fiction ones over again, when I was at school I won a prize in English and we could choose three books, I still have them in my collection, I also have quite a few books on Anne Boleyn now, early ones by Friedmann ranging up to the most recent ones, Amy Licence’s book on Anne was wonderful and Weirs The Lady In The Tower, it is a very careful study of her final weeks from when she was arrested up to her sad death, Iv also biographies on Eleanor of Aquitaine another historical figure I adore, and other ancient kings and queens, I think I need to get another bookcase !

I sold enough books to fill my backseat and floor of my car to a used bookstore about 25 yrs ago or so. It didn’t btake me long to replace them. Though I don’t mind reading digital books and I have quite a few there is nothing like holding a real book in your hands and if it’s an old book smelling the musty pages. Reading is more than words. With a physical book it’s an entire experience.

I do agree I have a few books on my iPad but you cannot gain the same pleasure as holding a nice book in your hands, of course in its favour are the fact they do not take space up in your house, Tottenham Court Road in London is home to numerous bookshops, I can spend a whole day there, we have Foyles which is the largest bookshop in the world, before video and dvds and the internet was around, if I was off ill from school I could lose myself in my books, they do indeed take you to another world, it is as you say an enormous pleasure.

The one big disadvantage to e-books is though they may be in your library you may have removed it from your device(s) and if you want to look something up you have to go through the hassle of re-downloading it. With real flesh and blood books you look at the spine or cover and grab it. Do you remember when e-books first started it was was predicted they would be the death of printed versions? I just don’t see that happening anytime soon.

Yes it’s a faff like a lot of technological things these days, for the past two days I have been unable to get into my Apple TV account, I’m waiting for my nephew to come round he knows more about computers than I do, like you I cannot see digital books replacing actual books, they maybe popular on long train journeys and you have the light switch for convenience, but the feel of a book in your hands is special, especially if it’s a cherished book, like a gift or a rare copy you managed to purchase, and I also think books sitting on a shelf slightly lopsided have a charm all their own, like the odd plant and pictures they make the house look lived in and cosy.

If I have a doctor’s appointment or take my car to the shop and have to wait around e-books are perfect. I usually have a couple on my phone so I don’t need an additional device.

As to the sketch I agree with you that there is no resemblance to Jane Seymore except for the double chin. I have a feeling it will be proven someday to be ofAnne Boleyn but at the moment the experts just don’t feel comfortable without more proof to back that claim.

Eric Ives favoured the Holbein sketch and the half finished sketch, also by Hans Holbein with a gable hood which accompanied the drawing. In the latter Anne wears a dark golden brown English gable hood, edged with gold and her dress matches. Pearls decorate the headlines and her face is more rounded with a cute little curling nose. Anne’s brown eyes are clear. She wears a double necklace, a rich velvet dress and various unfinished versions came from Holbeins sketchbook. The companion sketch in her high necked nightgown bears the exact same features as is a hallmark Holbein. Michael, there is some evidence that the name was added later, but by someone who knew Anne well, but it could certainly be contemporary.

The NP and Hever copies are favourites because of the French hood and the style of dress was only found during the 1520s and 1530s. Anne favoured the French hood as in these portraits and others show the same face shape and French hood and the dresses are all a beautiful black dress, again iconic with regards to how we expect Anne to look. It’s a more expensive dress and therefore more suitable for a woman of her status. The Holbein may have been inscribed by Sir John Cheke a friend and tutor to King Edward vi in 1552 and who knew Anne as a fellow reformer. Reformers tendered to stick together and employ other reformers, just as Catholic families later made certain their servants were also Catholic, their lives and freedom depending upon it.

Roland Hui and Eric Ives favoured the National Portrait Gallery portrait and Ives has dismissed the Cheke inscription because he has misidentified people before. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean he was wrong in this case. If Henry wanted Anne’s portraits out of the way or it wasn’t PC to own one, maybe Cheke was given the sketch and hid it, putting her name on it after Henry’s death. It wasn’t PC and was dangerous to have an English Bible, a Catholic prayer book, a rosary, yet people kept them, hid them and brought them back out when it was safe to do so. It was only five years ago that a contemporary portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie was formally identified in Scotland. Before that everyone we had, every single image was actually his brother, Henry. The Hever Rose portrait is a copy of this portrait as is one by Lucus Hornbolte, same French hood, same dress and same facial shape and features.

But which is really authentic? The problem is we don’t really know, the NPG cannot even say it’s authentic, just original was made 1534 to 1536. Why? We all know Henry Viii had them all destroyed. Do we? Did he? Someone produce an actual contemporary source please, because until they do, we can’t confirm if he did or not. It’s another Anne Boleyn myth. Maybe both are authentic. However, seriously they look like two different women. Unless we can go back in time with our smart phone or ordinary camera, we won’t know what Anne looked like. I favour the sketch, it’s by an artist who was around the Court for a long time, who had a close association with Anne, producing works for her, her fountains, her gifts to Henry, a feature for her coronation and she was a significant patron. It’s not beyond imagination that he made several sketches to prepare not just one or even as gifts for her friends. Henry had many portraits done by Holbein or his school and if you were clever you had a copy done for your home. Anne’s own Courtiers certainly would have had a copy of one of her during her brief reign if one was done and more than one did exist. These were expressions of loyalty and as Christine says there were literally hundreds of sketches by Holbein found after his death. An artist did a painting in stages, more than one sketch was done, several in fact, it was brought together and believe it or not coloured by numbers. Charcoal, pencil, just about anything with an edge was used, although every artist had a style, materials, strokes and so on of their own. It was in fact almost like a DNA fingerprint.

There may be others hidden away though, in a tapestry, the tableau of a coronation drawing, there is one of Anne in her seating plan, although it’s really just a tiny scribble with a little face, just to outline where the Queen would sit, but it’s so cute, there are faces in the famous tapestries in our palaces and a number are Henry Viii and his wives. We should perhaps be looking for Anne in one of those, you will certainly find Thomas Wolsey and Katherine of Aragon and even Kathryn Howard in the ones at Hampton Court. The Black Book of the Garter may also be an abstract image of Anne Boleyn but the fact that it is her is unique in itself. It is evidence to research. It’s evidence of the relationship between the crown and the past, the crown and mythology and the crown and pageantry and art. It’s also evidence that Anne was still high in favour during 1534 and her relationship with Henry had not yet turned sour. It’s also gives us information about the nature of Anne’s Queenship. Here Anne is identified with one of the most powerful and cultured Queens in Medieval history, Philippa of Hainault, the wife of Edward iii, a woman of learning and grace, whom Karen Warner calls in her recent biography, the Mother of the English Nation. Philippa bore Edward Iii several sons and daughters so the implications here are that Anne is expected to do the same. In the image she is very clearly with child, a state she is believed to have been in during the first seven months of 1534. Anne sits in triumph, her child is healthy within her womb and this time it will be a beautiful son. She has a healthy daughter, she is proving to be fertile. Henry Viii was identified as Edward iii, the great warrior King, the father of his people, a mysterious King who loved the same Arthurian legends Henry did. He too is depicted in an image of chivalry and power. Anne is his counterpart, it’s a powerful image.

I also have far too many books and need to cut down on some. I love my Kindle though, it is particularly useful if I can’t find something amongst my thousands around the house. I sometimes take it with me if I have to wait around the hospital. It certainly cuts down on book luggage on holiday and the internet on here is really handy. I will be taking it with me to the legal representation on Friday, as we are fighting to save our home at the moment and we may be there for a time. The Government stopped paying for mortgage help last year and we are stuck between them and the company as they should have continued with some help, the company lost payments and the DWP paid a different company by mistake. Guess who is stuck in the middle, us! I can see this being a long drawn out project. Well tomorrow I am having a massage and this will have to wait. It’s Burns Night on Friday. We are not having Haggis, we are having Steak. After the last two weeks, we will deserve it.

Oh no what a worry I hope it gets sorted out Bq, let us know how you get on won’t you? xx

Sure will. I am keeping a daily log on Twitter. Cheers.

Good luck BQ, that’s a terrible situation to be in.

Good luck BQ, that’s a terrible situation to be in.

Cheers, seeing some housing place tomorrow who will help so had a better day today. It will sort itself out. The priority is to get the Court date postponed and there are enough issues to do that. Then they will help with negotiations. For one thing we have to apply for something so the Court will need to give something called a Time area to do that. I am confident of this being sorted out of Court and us selling the house ourselves. The Court can order them to negotiate and its usually a last resort. Our rep said they shouldn’t have left it so long to contact us and as the DWP were paying the interest, that means they have to contact us straight away. That needs to be investigated so a delay will be granted to do this. That should give several months to come to an agreement.

That sounds much more positive than yesterday.

Hope it goes well for you BQ.

I just heard that Terry Jones has died. Very sad. I’m a huge Monty Python fan and have been for 40+ years and one of my favorite comedies is Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in my my opinion the greatest documentary on medieval times ever made. His humor will be missed.

Michael Palin was literally sobbing when he was interviewed, he said Terry Jones was such a lovely person, I watched Monty Python in my youth it was funny, I don’t know if you like Blackadder it covers the medieval period up to the First World War, I find them tremendously funny.

Im not a bit surprised. The Python’s weren’t just work buddies, they were close friends. I first watched Flying Circus in the 70’s when the local PBS station would air a couple of episodes every Saturday night at 11pm. Holy Grail, Life of Brian and Meaning of Life I saw in the theater. A few years ago I found all 4 seasons of Flying Circus on YouTube and binged watched them. Fourty years on they were just as funny as ever. Yes, I know of Black Adder and have them all on DVD. I love Miranda Richardson as ‘Queenie’. I also have John Cleese’s series Fawlty Towers. Brilliant series with a great cast. If you haven’t seen it look on YouTube for John Cleese’s eulogy of Graham Chapman from 1989. It is very funny. Cleese and Chapman were pretty close so keep that in mind when you watch it. It will give you a chuckle.

Yes I preferred the Tudor series and the Georgian saga to the medieval one, it was hilarious also Fawlty Towers, another brilliant comedy, growing up I loved Bewitched with Elizabeth Montgomery, when Dick York left because of a back injury I was upset because although his replacement was good, you get used to the first actor, it was a really funny series and all the actors were brilliant, being in other sitcoms and movies as well, Agnes Moorhead who I read was not all that keen on her role, and Aunt Clara ( Marion Lorne) she was in a Hitchcock movie as well, all my family loved Bewitched and I was very sad when Montgomery died she was lovely, another brilliant comedy from the 60’s was The Munster’s with Fred Gwynn and the cousin who lived with them, because she was normal they all thought she was ugly ha!

Sargent Bilko was funny my dad loved to watch him, a lot of television was good in the sixties and seventies, over in Britain the seventies has been called the golden age of television because there was a lot of good sitcoms, as well as drama, one thing the BBC always had were very good writers, trouble is now they have gone all PC, ah well sign of the times.

I agree about Black Adder. The Tudor and Regency series were definitely the best ones. According to the commentary by Rowan Atkinson on the dvd’s the problem with the first series was they didn’t know where it was going. I do love the set up though of Richard III being killed accidentally by Black Adder and Henry Tudor trying to escape. After that however, though there were some funny moments (the Witch Smeller Persuivant comes to mind) it was kind of all over the place.

I loved Bewitched. As a kid I had a huge crush on Elizabeth Montgomery. Your right about Dick Sargent. He was a good Darren Stevens but Dick York WAS Darren Stevens.

Ive only seen a handful of Sgt. Bilko episodes. Loved what I saw. Phil Silvers was a very funny man. I msinly know him from other programs. So many great shows from the past that they wouldn’t dare make today. Monty Python could not exist in any form. Sad

I’m just glad we can get most of them on dvd now.

Another comedy series I have on disc is Are You Being Served. One of the best comedic ensembles I’ve ever seen. Talk about a non pc show. Wow!

Oh yes I record that it’s on every day at the moment, the old boy young Mr. Grace was the best I think, he was so cute, and Mrs. Slocombe with her ever colour changing bouffant, the film they done was funny when they went to the Costa Plonka, Dads Army is a classic of course, when the BBC show that they say their ratings always go up, The Good Life was great to, nearly all of those actors are dead now.

For the longest time I had wondered why the actor who played Mr. Granger abruptly left. I thought maybe for some reason the producers had let him go but in cast interviews on the DVDs they explained that during hiatus between series his wife had died and though he was welcome and encouraged to come back his heart wasn’t in it anymore and sadly he too passed away not long after. They brought different characters in to fill those shoes but Mr. Granger could not be replaced. He was one of my favorites.

Yes everyone said he looked a bit like Churchill.

I didn’t like the one who replaced Harold Bennett as young Mr. Grace, and I preferred Trevor Bannister as Mr. Lucas to the ones who followed after, Steptoe and Son I loved to, Harry H Corbett died of a heart attack quite young before Wilfred Brambell, Brambell was a pervert ended up in the newspapers, but good actor though, Porridge was great sadly Richard Beckinsale also died young of a heart attack, his daughter Kate who you must have seen in Pearl Harbour, she really is remarkably like her father.

Yes, heard the other day or was it yesterday about Terry Jones, only in his 70s, so sad he and the Monty Pyphon crew were great. I have several books by Terry Jones, the Crusades which when they did the series on TV he managed to make a serious but hilarious four part documentary. I loved the bit where he did the Crusade Recruitment Campaign, a black and white film, introducing the main protagonists from the First Crusade, and he was playing all of them, it was really funny. Some of the stuff he dug up, like one of the first battles, the Muslims preferred mares to stallions in battle, easier to control, so the Franks used stallions and guess what, the mares were on heat and ran off, chased by the Franks. It was inevitably an overwhelming victory for the Franks. (The Franks was the name given to Christian Crusaders as most of them came from ex Frankish states and were of Frank and Norman descent.). It was a great series and he did consult experts of course, it was fascinating stuff as always, but his own personal touch brought it to life. He also did “Medieval Lives” “The Barbarians” which is about the Gauls and Goths and others who took over from the Roman Empire, including my favourite Ancient people, the Persians, who unlike the Greeks didn’t keep slaves. I think there were a few more but I can’t recall them all.

The Blackadder series were great. Miranda Richardson the best Elizabeth I by far. I loved the First Series because Baldwick had brains and Blackadder didn’t. I love how poor Richard iii was killed taking the horse and by mistake and haunted Blackadder, who obviously had a weird sexual fettish because there was a joke about him having a sheep in his room when it was Henry Tudor hiding in there. I love the complete reversal of history, with the Yorks winning the Battle of Bosworth, the Kings brother, Brian Blessed becomes King Richard iv because the real Richard is accidentally killed and Henry Tudor has to run for his life and hides in Blackadders rooms. Richard iii is a ghost and haunts him, then the banquet is haunted by him but nobody can see him but Blackadder so they ignore him and he pops off. The second series is good, but I think the Third with Stephen Fry is good and the Prince Regent as a skinny man, which he wasn’t was totally absurd but really funny. Blackadder inherited the crown at the end while Hugh Laurie gets blown up by a canon ball. The WW One was special, especially the ending, very emotional.