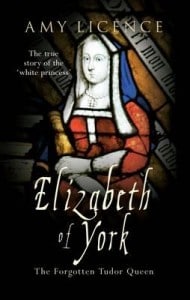

Today we welcome author and historian Amy Licence to The Anne Boleyn Files as part of her virtual book tour. Amy has kindly shared an extract from her book Elizabeth of York: The Forgotten Tudor Queen (taken from the chapter ‘A Royal Wedding, 1485-1486’)…

Today we welcome author and historian Amy Licence to The Anne Boleyn Files as part of her virtual book tour. Amy has kindly shared an extract from her book Elizabeth of York: The Forgotten Tudor Queen (taken from the chapter ‘A Royal Wedding, 1485-1486’)…

Predictably, early Tudor chroniclers were full of blessings for the match. The fourth Croyland continuer wrote that the marriage, ‘which from the first had been hoped for’, was lauded for the sake of Elizabeth’s title as well as her virtues: ‘in whose person it appeared that every requisite might be supplied, which was wanting to make good the title of king himself’. He cites a poem included by the previous Croyland writer that ‘since God had now united them and made but one of these two factions, let us be content’. Other writers celebrated that ‘harmony was thought to discend out of hevene into England’ from this ‘long desired’ match. Shakespeare presents them as the ‘true succeeders of each royal house, by God’s fair ordinance conjoin together’. Their heirs would bring ‘smooth-fac’d peace, with smiling plenty and prosperous days’. Hall claimed the match ‘rejoiced and comforted the hartes of the noble and gentlemen of the realme’ and ‘gained the favour and good minds of all the common people’. On 10 December, the Speaker of the Houses of Parliament stated that Henry wished to take Elizabeth as his wife ‘from whence, through the grace of God, it is hoped by many the continuation of offspring by a race of kings, as consolation to the entire nation’. Henry also sought to obtain a second papal dispensation for the match, as the pair were related within the fourth degree: he already had one dating to March 1484 and could not allow any possibility of the marriage being invalid. This involved religious and legal specialists giving depositions about their respective lineages before witnesses, which was confirmed by the current papal legate to England, James, Bishop of Imola. He was successful on 16 January. Two days later, Elizabeth and Henry were married.

No actual descriptions of the wedding survive. The ceremony was conducted by Archbishop Bourchier, who placed the gold ring on Elizabeth’s finger and heard the couple repeat their vows. Certainly there would have been much pomp and ceremony, which, as the astute Henry Tudor had swiftly grasped, was the key to impressing his majesty upon witnesses. In a similar style to his Coronation, the abbey would have been decked out in the exclusive colours and fabrics of royalty: purple and gold, silk, ermine and delicate cloths of tissue. Elizabeth would have been splendidly dressed and adorned with jewels, lace, brocade and ribbons; the choice of white for wedding dresses was not yet an established tradition so she may have worn one of the rich purple, blue or tawny gowns that appear among her wardrobe records that year. The portraits in which she was depicted can give an idea of the magnificence of her dress, as these would also be opportunities to display wealth and status. An anonymous work in the early Tudor style shows her dressed in ermine cuffs, with embroidered borders studded with pearls and heavy, symbolic jewellery. It is clear from Henry’s later accounts that in spite of his historical reputation as a miser, he did not stint when buying jewels and adornments for his family: it has been estimated that between 1492 and 1507, more than £10,000 was spent from the royal budget on such symbols. As the couple repeated their vows, lit by burning tapers, they stood before a host of the decimated English nobility, summoned by Henry in order to witness the union which, hopefully, would bring peace. Elizabeth’s private feelings on this occasion must have encompassed pride and relief as well as a degree of uncertainty. Although it was a moment of intense personal triumph, she had witnessed her mother’s own tumultuous journey as queen and understood that the ceremony brought no guarantees. She was about to experience an irrevocable change in status, not merely as queen but as a woman becoming a wife. It must have been a bitter-sweet moment, aware as she was that her triumph had come about as a result of her family’s losses and suffering. But this moment was symptomatic of her life to date. Only recently, she had been enclosed within the restricted walls of Westminster sanctuary; here she was now in its abbey, becoming the wife of the king. Through the course of the extravagant feast that followed in Westminster Hall, she must have been aware of the approach of that symbolic event; the public ritual of the bedchamber.

Henry and Elizabeth’s wedding night was probably spent in Westminster’s painted chamber, the palace’s most luxurious apartment, containing bed, fireplace and chapel, richly decorated as its name suggests. It was habitually Henry’s chamber, dominated by a four-poster bed that required preparation by ten attendants who would search the straw mattress with daggers to discover any potential dangers, before the ritual laying down of sheets, blankets and coverlets. Accounts paid to Elizabeth’s bedmakers in 1502 give an indication of the kind of luxury available to the king and his new wife. In October, London mercer Thomas Goodriche received payment for the delivery of 60 yards of blue velvet for the queen’s use. The following month, John Warreyne was paid for the ‘making of a trussing bedde seler testere and counterpoint of crymsyn velvet and blew paned’. The bed also had a matching curtain of ‘dammaske crymsym’ with blue panels, sewn with red thread and hung on green rings. He also supplied linen cloth and fine white thread for sheets and curtain linings with a white fringe. As they prepared for their first official night together, the couple were still enacting a vital part of the wedding ceremony. In 1501, Elizabeth would help organise the wedding of her eldest son, Prince Arthur, and Catherine of Aragon, which may have been shaped in part by her own experiences. It was usual for the royal bride to be escorted to her chamber by her ladies, undressed and put to bed. Such rituals took place in many towns and villages, in all walks of life, as the culmination of a day’s celebrations. The partially undressed bridegroom followed, accompanied by his gentlemen and musicians, who would mark the occasion with bawdy jokes and ‘rough music’ or charivari. For a king and his wife though, the event would be less raucous and more religious: priests and bishops would pronounce their blessings and sprinkle the bed with holy water before wine and spices were served. Sometimes, before they left, onlookers required the naked legs of a couple to touch or to witness a kiss in order to leave satisfied, as in the case of Princess Mary Rose, whose marriage to Louis XII of France in 1514 was considered consummated when her bare leg touched that of his proxy. One such scene occurs Marie de France’s twelfth-century Lais le Fresne when the heroine prepares the marital bedchamber by adorning it with the distinctive brocade that leads to her discovery. Similarly, Henry and Elizabeth’s chamber may have been decorated with suitable silks, ribbons and hangings. Finally though, the newlyweds were left alone. The consummation of a marriage was a vital stage of its validity; without it, all the church’s ceremonial and ritual could be dissolved and the legitimacy of subsequent heirs and inheritance drawn into question. Even among people of lesser rank, unions could be broken through non-consummation; Edward IV’s mistress, Jane Shore, gained her freedom in this way, while for Elizabeth’s future daughter-in-law, events of her wedding night would later contribute to her undoing. However, history was to prove that the wedding of January 1486 was successfully consummated, if it had not already been so.

You can read my review of Elizabeth of York over on our book reviews site – click here.

Giveaway

Giveaway now closed.

Amberley Publishing have kindly offered one copy of Elizabeth of York to one lucky Anne Boleyn Files follower. All you have to do is comment below saying why you’d like to read this book. Your comment must be left by midnight (GMT) on 11th May. A winner will be chosen at random on 12th May 2014 and announced here and on our Facebook page. The giveaway is worldwide.

Here are the rest of the stops on Amy’s tour (and more chances to win a book!):

- Saturday 3 May, On the Tudor Trail- Retracing the steps of Anne Boleyn will host an extract from ‘Cecily Neville: Mother of Kings’.

- Sunday 4 May, Queen Anne Boleyn Historical Writers – Queenanneboleyn.com will host an extract from ‘Anne Neville’.

- Monday 5 May, Anne Boleyn: From Queen to History will host an extract from ‘Elizabeth of York’.

- Tuesday 6 May, theroyalfirm.com will be posting a Q & A with Amy about her ‘Richard III: the Road to Leicester’ book.

- Wednesday 7 May, The Anne Boleyn Files will host an extract from ‘Elizabeth of York’.

- Thursday 8 May, Nerdalicious will be posting a Q & A with Amy about her ‘Cecily Neville: Mother of Kings’, along with an extract from the book.

- Friday 9 May, www.anneboleynbook.co.uk/ will host an extract from ‘Anne Neville’.

- Saturday 10 May, On the Tudor Trail will hosting again, this time sharing Amy’s answers to ’20 questions’.

- Sunday 11 May, Tudor Book Blog will be hosting an extract from ‘Richard III: the Road to Leicester’.

- Monday 12 May, tudorhistory.org/blog/ will host an extract from ‘Elizabeth of York’.