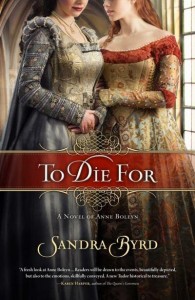

Today we have a real treat. Not only do we have a guest article from Sandra Byrd, author of “To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn”, but we also have a special “To Die For” competition. See the next post for competition details, but for now please enjoy Sandra’s article and my review of Sandra’s novel at

Today we have a real treat. Not only do we have a guest article from Sandra Byrd, author of “To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn”, but we also have a special “To Die For” competition. See the next post for competition details, but for now please enjoy Sandra’s article and my review of Sandra’s novel at

From a young age, we women are wired for friendship. Little girls link arms in exclusivity with one another on the playground. The most devastating betrayals during our middle and high school years often come not from boys but from the friends we thought loved us and in whom we’d trusted. I have several friends with whom I’ve been close for more than twenty years and I know they have my back, and I, theirs, no matter what. So when I began to write novels set in the Tudor period I wondered, who were these Queens’ real friends, those who would remain true in a treacherous court? Ovid wrote, “While you are fortunate you will number many friends, when the skies grow dark you will be alone.”

I began with Anne Boleyn.

I have been drawn to Anne since I was a girl, curled up in a beanbag chair, dog-earring books about her as I read and re-read them. My research journey took me to Meg Wyatt, narrator of my novel, To Die For. I will quickly note that in my book I have switched the names of the Wyatt daughters so that the eldest is named Anne/Alice and the younger Margaret/Meg so that the story could be told without two “Annes” to confuse the reader. It began, as all treasure hunts do, with one solitary clue, an offhand comment in a Tudorplace.com.ar link that said that Anne Wyatt attended Anne Boleyn till her death, and that, at the end, Anne Boleyn had given her friend her prayer book, a very personal gift indeed, and just before her execution whispered something in her friend’s ear.

The Wyatt family is ancient and is able to be traced back many centuries before our story picks up with Henry Wyatt, father of my heroine Meg and her siblings, including poet Sir Thomas. History of Allington Castle, assembled and published by Sir Robert Worcester, the castle’s current owner, states that Henry Wyatt was a “fervent Lancastrian and supporter of Henry Tudor, who suffered imprisonment and torture for two years in a tower in Scotland under Richard III for resisting Richard’s pretensions to the throne.” When Henry Tudor ascended to the throne after his victory on Boswell Field in 1485, he freed, knighted, and bestowed lands and estates to his friend and supporter, Henry Wyatt.

As is so often true when tracing ancient family trees, there are varying accounts of Henry Wyatt’s marriage(s), a veritable spaghetti tangle of leads and possibilities. Some say Wyatt married only one wife, Anne Skinner, whereas other accounts have him first marrying Margaret Bailiff and then, after her death, marrying Anne Skinner. I subscribe to the former argument for a number of reasons. First, the marriage to Margaret was to have taken place in 1485 and, as he was newly free and well-to-do, that made good sense for timing for a marriage of a twenty-five year old man. Had he married only Skinner, Wyatt would have been forty, a possibility, but a late first marriage was not something he encouraged among his own children.

A daughter, Margaret, or Margery, was soon born from this union. This same daughter would go on to marry John Rogers and have a child, another John Rogers, who would become the first Protestant martyr under Queen Mary Tudor. John Rogers the younger’s biography by Tim Shenton, among other sources, claims that Rogers was born in 1500, which means that his mother can’t have been born much later than 1485 – she’d have been fifteen-years-old at his birth even then. Henry Wyatt’s first daughters were known to be Margaret and Anne respectively. In accordance with traditions of the time, it seemed likely to me that each girl may have been named after her mother.

Some sources have Margaret, Lady Lee, born in 1506. Because of the marriage set up as explained above, I believe Lady Lee to be the daughter of Margaret Wyatt Rogers, also named for her mother, and therefore the granddaughter of Henry Wyatt, not his daughter. She’d have been born six years after John Rogers, her brother. Their mother was known to have had many children. Some sources have Margaret Wyatt Rogers marrying Antony Lee after the death of her first husband, but I think the age difference was considerable and it makes more sense to have her daughter marrying him, bearing Sir Henry Lee at age 25 in 1533.

Anne Skinner, certainly Henry Wyatt’s wife, had at least one son, Thomas, the poet and courtier, born in 1503 and at least one daughter, Anne, whom I placed as having been born in what I believe to be Anne Boleyn’s birth year of 1501. The families lived nearby one another in Kent, the Boleyns at Hever and the Wyatts at Allington, and it is certainly reasonable to think that the families knew one another, as both Henry Wyatt and Thomas Boleyn were experienced and admired courtiers and families did entertain with their neighbors. Worcester, in his book Allington Castle, tells us that “in 1511 Thomas Boleyn and Henry Wyatt had received jointly the ‘constableship’ of Norwich Castle,” so they certainly worked together.

We know a little about Sir Thomas Wyatt’s life, from his allegedly miserable marriage to Baron Cobham’s daughter Elizabeth Brooke, his continuing, and foolish, flirtations with Anne Boleyn, and his son’s rebellion for The Lady Elizabeth. Thomas’s father, Henry Wyatt, was said to have claimed that if Thomas were innocent, when he was imprisoned during Anne’s crisis in 1536, the king would surely let him go. It is thought, however, that Sir Henry did eventually intercede for Thomas through Cromwell, and Thomas was soon freed.

We know relatively little about the Wyatt sisters. Because of John Rogers’ reformist convictions to the point of martyrdom, and Anne Boleyn’s strong reformer leanings, I have written the Wyatt sisters to be people of honest questioning but, eventually, firm faith. Because one sister was closer to Anne Boleyn in age, at least in my opinion, (the elder sister would have had a child nearly the same age as Anne Boleyn) I have made the younger Anne Boleyn’s dearest friend. Certainly she was Anne’s Mistress of the Robes, a position of high honor, trust, and intimacy. There were good times – and Mistress Wyatt was there with Anne to share them. But she was there at the end, too, when there was no honor in being the confidant of the Queen. When Anne needed a friend to mark the last hours, to walk with her to the scaffold, to witness her death without flinching, and to ensure that she was properly wrapped for burial, her friend Meg Wyatt was there.

Perhaps Ovid wasn’t completely correct, or perhaps not in this case. When the skies turned dark, Anne Boleyn did not have many friends. But in Meg Wyatt, she had at least one.

You can find out more about Sandra at her website, www.sandrabyrd.com and do check out my review of Sandra’s novel, “To Die For” – click here, it’s a wonderful read. Sandra has also donated some goodies for our competition – see https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/to-die-for-competition/10466/ – Thanks, Sandra!

Thank you, Sandra, for this lovely article. I have read your book (reviewed it actually) and enjoyed it very much. Best of luck with it!

Anne Skinner, whereas other accounts have him first marrying Margaret Bailiff and then, after her death in 1594, marrying Anne Skinner.

I think there’s a typo there.

Thanks, Anyanka, I didn’t spot that one!

I myself don’t have the time to write an article now (drat!) but I would LOVE to see someone write on Eustace Chapuys! Let’s hear more about the man who probably had more power and influence on the Tudor Dynasty than any other non-Englishman (or woman) on earth.

I have never understood why we have so little information about the women or affairs of Chapuys when he lived for so many years at the English court. We rely on his writing for so many details of others, but we have very little information on who this powerful man was personally.

Anyone game?

I am a fan of Chapuys, and I think he was a fascinating man…I’m game!

He is heavily criticized and dismissed, and I think he needs to be rehabilitated!

I agree. People criticise him because he was ‘anti’ Anne Boleyn and I’ve heard people say that historians rely far too much on his letters but his letters are amazing primary sources, we’d be lost without them.

I have always wondered about him as well.

Thank you, Anne, for reading and reviewing my book. I know there are many books to choose from. I love Anne, of course, and it was pure pleasure to get to know more about the Wyatts.

I do not have the time to write an article either right now. If I did I would write about Laetitia Knollys. The daughter of Katherine Carey, the alleged illegitimate daughter of Henry the Eighth and Mary Boleyn. She did look suspiciously similar to Elizabeth the first 😉 and caused quite a stir in her court by marrying her favorite Robert Dudley.

Can’t wait to read your book, Sandra! It looks like it will be a great read.

Unfortunately, I don’t have time right now, either–am too busy putting finishing touches on the next book, due Sept 1. But I’d love to know more about those already mentioned as well as Douglas Sheffield and Sir Christopher Hatten–isn’t he the one who some people think might have had some sort of sexual dealings w/elizabeth? A letter to him from a friend, giving him advice on how to proceed now that the queen had “had her way with him” or something like that–oooh, I wish I knew!

Thank you, Sara. I hope you do enjoy it!

I would love,love,love to see something written on Douglas Howard!

I am a renaissance actress and often portray Douglas.

I play her as I whole heartedly believe she was; Robert Dudley’s FIRST secret wife. She too was a cousin to Elizabeth,and bore Dudley a son; the only one to survive, but sadly she is very much forgotten. Please do let her voice be heard finally.

I ran across this article while working on my genealogy. Apparently, Anne Wyatt is my 13th great-grandmother. Wow!

With all the conflicting information, I’m still trying to sort it out. In my journey through the shades of my ancestors, it is the stories that are priceless. I’m so glad you told this one, and now I just have to get the book!

It seems I have some things in common with Margaret Wyatt, my 16th great-aunt. I would have been on the scaffold of a friend too. Perhaps someday I will write my story.

Thanks for posting this marvelous work!

I am the 10th great granddaughter of Margaret Wyatt. I must say I enjoy reading anything you have on the family. Thank you for all you have done. They all interest me as much as you.