Today, we have a guest post from David Rayner, who spent many years re-enacting the life of a Benedictine monk and who has vast knowledge of monastic life. I began corresponding with David when he commented on my articles on the series Tudor Monastery Farm and I’m so pleased that he agreed to write this article on what life was like for a monk in the medieval era – thank you David. Over to David…

Today, we have a guest post from David Rayner, who spent many years re-enacting the life of a Benedictine monk and who has vast knowledge of monastic life. I began corresponding with David when he commented on my articles on the series Tudor Monastery Farm and I’m so pleased that he agreed to write this article on what life was like for a monk in the medieval era – thank you David. Over to David…

I admit that I chose as a title this Latin phrase, meaning “manner, custom or law of the monasteries”, because of a decorated capital from an early 12th century manuscript. It shows two Benedictine monks folding a long piece of linen, together forming the capital M of the word mos. It is also a misleading title, since each monastery differed in its daily routine from every other; timekeeping was very far from accurate or universal and each Order of monks interpreted the Rule of St Benedict in a different way. The many feast days in honour of particular Saints and the major Christian festivals also changed the normal schedule.

The Regula Sancti Benedicti, written in Italy in about 530 AD, became the framework governing the lives of all monks in England for a thousand years – and for much longer in the rest of Europe. It covers within its 73 chapters almost every aspect of the daily routine, from food to behaviour and from bedding to the Holy Offices (church services). Humility and placing God first in all things are at its heart. Benedict himself did not consider his Rule either complete or applicable outside his own monastic community, but nevertheless it quickly spread and became The Rule for monks.

Let us imagine a typical Benedictine monk, if there ever was such a thing, at an abbey somewhere in England in the late twelfth century. We need to specify a time period because, like every other aspect of life, the monastic routine evolved and changed during the very long medieval era.

The religious day begins on the previous evening. An echo of this survives in phrases like “Christmas Eve” and “All Hallows Eve”, but most people today have no idea why the “eve” of a feast day should be significant. Our monk certainly knew, because it was explained to him and he had to prepare himself mentally and spiritually for the following day.

It is about 8:30 in the evening. He joins the other forty or so monks as they make their way in total silence up the “day stairs” to the huge communal dormitory on the east side of the cloister. They walk, as always, in order of seniority. Speech is forbidden at this time and at various other times throughout the day; if a monk needs anything he indicates it by means of sign language, but tonight there is nothing to disturb the tranquillity of the routine. Our monk removes his leather belt with its knife sheath attached, since the Rule is very careful to avoid any possibility of accidents during the night. Remaining fully dressed, but replacing his leather shoes with warm “night shoes” (probably something like thick socks of felted wool), he pulls back the sheet and single wool blanket covering his straw mattress and settles down, falling asleep almost as soon as his head touches the down-filled linen pillow. The dormitory is unheated and stone tallow lamps (cressets) are kept burning throughout the night, so it is never fully dark.

It is now shortly before 2 a.m. and he is gently shaken awake by the brother sacristan to the deep sound of a bell in the tower at the west end of the church. Still more than half asleep, he forces himself to rise and take his appointed place in the procession of monks heading for the “night stairs”, also lit by stone lamps, which lead directly into the choir of the church. It is cold, dark and drafty and he is longing for the comfort of bed, but Psalm 94 soon begins and he joins in with the familiar Latin words, the text and soaring music learned by heart. He gains encouragement from the meaning of the opening words and the intense spiritual beauty of Gregorian chant:

“Come let us rejoice unto our Lord, let us make joy to God our saviour: let us approach to his presence in confession, and in Psalms let us make joy unto him.”

In this monastery the night service (let’s call it Matins) is followed immediately by a second (Lauds). Both consist of sung Psalms, hymns, prayers and responses, followed by prayers for the king and his family and for the wealthy patrons of the abbey, all in Latin. Over the course of a week all 150 Psalms will be sung. After Lauds the monks return to their beds for a few hours.

At about 5:30 our monk is again woken and after tying on his belt and changing into his leather shoes he joins his brethren in the “rere-dorter” (Anglo-Norman French for “behind the dormitory”, a polite term for the latrine block). Here they answer the call of nature, wash their hands and faces in cold running water and comb the hair surrounding their Roman tonsures. Dry towels are provided from the monastery’s store room. As quickly and quietly as possible they proceed directly to the cloister, where each monk has left a book which he takes up and reads to himself. It is just a short time before the bell sounds for the office of Prime (the first daylight service) at about 6 a.m.

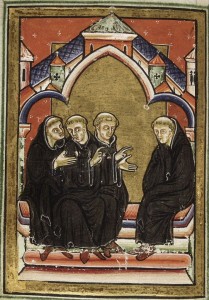

After Prime there is another short interval for private study before the daily meeting in the Chapter House, which is also located on the eastern side of the cloister. Our monk takes his appointed place on the stone bench which runs around three sides of the large, unheated room. The meeting starts with a reading of a chapter from the Rule, a constant reminder to all the monks of their responsibilities and regulations, and then the week’s tasks are allocated by the father abbot. Our monk is detailed to assist in the kitchen, while others are assigned to the infirmary, the gardens, the bakery or brewery, the orchards, the fishponds, the cellar (stores), the hospital (guesthouse) or routine duties at the various altars; those with skill are assigned to work on manuscripts in carrels in the north walk of the cloister. An announcement is made of the death of a fellow Benedictine in a monastery many miles away, whose name is added to the list of departed souls for whom prayers will be said. Finally, disciplinary matters are dealt with; brother Walter is accused of nodding off during Lauds and he accepts his thrashing without protest, while the other monks, their heads covered by their cowls, pray silently for him.

The monks are dismissed and each goes immediately to his appointed workplace after collecting any tools, materials or containers he needs from the brother cellarer. Our monk puts on his scapular, a long length of black woollen material with a hole for his head, which will keep his habit clean as he works. In the kitchen at the south-west corner of the cloister he is tasked with preparing onions, leeks, field beans, peas and other vegetables for the pot, using knives stored in the pantry. A stone channel provides a constant supply of cold water for cleaning the vegetables and his hands, while pots and knives are first scoured clean with fine sand.

At about 9 a.m. all the monks leave their work and remove their scapulars before returning to the church for the next service, Terce, which followed by a sung Mass. Returning again to the cloister, each monk finds his own book and reads quietly to himself for the next 90 minutes; our monk has a beautifully decorated copy in Latin of St Augustine’s Confessiones. He must read the text many times, analyse its meaning and apply its teachings to his own thoughts and deeds. He must consider its messages very carefully and seek deeper truths behind the text – this explains why monks are each given just one book to read for an entire year, before exchanging it for another from the library collection.

It is now about 11:30 and the great bronze bell summons the monks to the next service, Sext (the “sixth” hour of the day), which lasts about 20 minutes. There is then time for our monk to wash his hands in the lavatorium or washbasin outside the refectory on the south side of the cloister. He remembers to make sure his own knife is clean by scouring it in the sand provided near the stone washbasin. A little bell sounds to announce that the midday meal is ready – the first meal of the day.

In strict order of seniority the monks enter the refectory and take their places without speaking, all facing inwards with their backs to the walls. Lay servants bring the dishes of food to the tables and any specific needs are indicated with sign language. Father abbot gives the grace in Latin before the small bell rings to give permission to start eating. While the monks eat in silence, one of the brothers (who has already eaten in the kitchen) stands in a pulpit and reads aloud from a religious text. In this way both the stomachs and souls of the monks are nourished.

The meal consists of cooked vegetable dishes, fish, bread, cheese, butter or lard and fruit when it is available. It is the same menu as almost every other day, with almost no variety except for occasional “pittances” of eggs, poultry or pastries. The meat of four-legged animals is strictly forbidden and among the rival Cistercian Order no animal fats are allowed, making their menus even more restricted. Both wine and ale are served (not beer, which is not made in England at this time), but both are low in alcohol content. After the meal a prayer is recited by the abbot and the monks return to the dormitory in silence for a brief siesta – this is the end of summer and the days are still long.

Our monk is unable to sleep, choosing instead to repair one of his tan leather shoes with the needle and linen thread carried by all the brothers. He could simply report the loose sole to the cellarer and obtain a new pair, but he is content to put in a few stitches and keep them going a bit longer – they are comfortable and a new pair might not be so agreeable. He is careful not to disturb anyone else.

It is now 2:30 and the bell is sounding for Nones (the “ninth” hour), a short service followed by a drink of weak ale.

Putting on his scapular again, our monk spends the next three hours in the kitchen and refectory, cleaning the utensils, replacing soiled tablecloths, washing and drying the linen, dishes and bowls, returning each item to its allotted place and ensuring the long refectory tables and those in the kitchen are clean. The floor is covered with rushes and sweet-smelling strewing herbs which are swept away and replaced from time to time. Leftover loaves of bread and other foods are collected and given to the brother porter (gatekeeper), who will distribute them daily to poor people who wait outside for alms. Moderate conversation is allowed during work periods, except for the scribes working on manuscripts – they must concentrate solely on the intricate text and illuminations – but frivolous and unnecessary speech is banned.

The office of Vespers is held at about 6 p.m., followed by prayers for the saints and the souls of the departed. As it is still the summer routine, our monk is permitted a very light meal after Vespers, consisting mainly of bread, cheese and raw vegetables. This is followed by Vigils for the Dead, then an evening drink called poculum, usually wine or mead in the cloister, before returning to the church choir for a short reading (“collation”) and the final service of the day, known as Compline. The abbot, as officiating priest, ends the day with a blessing on all the monks before they retire to their beds.

Our monk is almost always tired, frequently cold and hungry and he has no free time. He has no money or possessions, nothing to remind him of friends or family and no contact with anyone outside the walls of the precinct. The monastery is his entire world and he rarely ventures beyond the church and the claustral range of buildings. Yet he knows with the conviction of true faith that serving God clothed in a habit of humility, constantly striving to emulate the angels in praising God will ensure his soul’s eternal salvation.

About David

My name is David Rayner, I am retired and I live with my wife near Canterbury in Kent. I was educated at Grammar School in Weymouth, Dorset, where my interest in history and languages was inspired and nurtured by some exceptional teachers.

For many years I have been involved in living history, depicting a 12th century Benedictine monk, and this has allowed me to visit (and sleep at) many historic sites around the country. I have fond memories of explaining Anglo-Norman French monastic terms to a French visitor at Castle Acre Priory in Norfolk; as a French speaker he found them incomprehensible. My portrayal of a churchman must have been fairly convincing, as I was once asked by a lady visitor if I would hear her confession. Naturally I politely declined. I also appeared (fleetingly) on Time Team during the “Big Dig” at Canterbury. Sadly I am now forced to retire from this hobby due to ill health, but my interest and research into 12th century England continues.

I have written for BBC History magazine and various other publications, including a German historical journal which commissioned an article on 12th century pilgrimage in Europe. This led to my assisting with research for a forthcoming series on BBC2 on the subject of medieval and contemporary pilgrimage.

David has pages on the Feudals website, the 12th century group he has been involved with. These pages look at the medieval Church in general and also give details of monasteries, monks and nuns – see http://www.feudals.org.uk/the-church.html

Images:

- The monks forming the capital M mentioned in the introduction, taken from Gregory’s Moralia in Job written in 1111.

- A photograph of a monastic cresset (multiple stone tallow lamp) at Brecon.

- Benedictine monks seated in chapter, from the Life of St Cuthbert produced at Durham in about 1180.

- David Rayner dressed as a Benedictine monk.