Thank you so much to historical novelist Richard Masefield for sharing his research and views with us today.

Thank you so much to historical novelist Richard Masefield for sharing his research and views with us today.

Richard is interested in starting a dialogue on this image; he really wants to hear your views, so please do share your view by leaving a comment below this article.

Over to Richard…

By comparison with numerous ‘workshop’ versions, this rediscovered print from an apparently lost portrait of Anne Boleyn has every appearance of an authentic likeness, with its claim to represent Anne supported by Sir Roy Strong’s Tudor and Jacobean iconography and Eric Ives’s work in establishing a link between the portrait style and the gold and enamel image in the ‘Queen Elizabeth’s ring’, currently held by the Trustees of Chequers.1

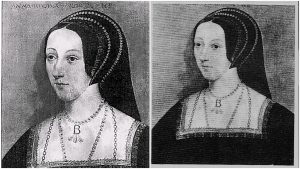

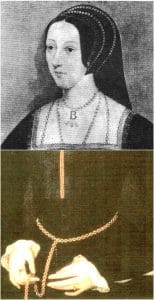

Two copies of the print have so far emerged – one revealing the inscription near the top: ANNA BOLINA UXOR 2 HVIII, perhaps added at a later date, and the other, of lesser quality, showing a little more of the shadowed background to the portrait and of the sitter’s wide black sleeves.

It would not appear that the portrait is by Holbein. But in style and pose it does correspond closely to other contemporary female paintings by the German artist, Joos van Cleve, particularly his 1530 portrait of Eleanor, Queen of France (below).

Moreover, there are good reasons for supposing that Van Cleve had the opportunity to paint Anne Boleyn in 1532. His well attested portrait of Henry VIII has been dated for the early 1530s and it has been suggested that Van Cleve came to England for the commission. According to the Royal Collection Trust, this portrait ‘may have been painted to commemorate his visit to Calais in 1532’. In fact, it is more likely that the King sat for the artist in Calais or Boulogne during the visit itself; and it follows that a portrait of Anne Boleyn by Van Cleve could also have been undertaken while she was there with him. It is known that Van Cleve was summoned to work at the French court by François I in the early 1530s,2 and the 32 days Henry and Anne spent in France in the autumn of 1532 would have allowed ample time for preliminary sketches, if not for completed portraits.

The question of how a portrait of Anne Boleyn, sketched in 1532 and perhaps completed in time for her coronation in 1533, survived her disgrace and death in 1536, when other images of her were deliberately destroyed, might be explained by the fact that artists were frequently required to undertake multiple versions of royal portraits. Van Cleve was known for his ‘impressive studio organisation and collaboration’,3 and at least two versions of his portrait of Eleanor of France survive, wearing different costumes and jewellery.4

There are also two copies of Henry VIII’s portrait by Van Cleve, both of good quality, in the Royal Collection and that of Burghley House.

If Anne Boleyn did sit for Van Cleve in Calais, one would expect official versions of the portrait to feature jewellery obtained for her from Katherine of Aragon in time for the French visit;5 (e.g. the jewelled cross with pendant pearl in Katherine’s miniature by Lucas Horenbout, and worn successively by Anne in her portrait medal of 1534, Queen Jane in the Whitehall Mural and by Catherine Parr in another Horenbout miniature.) Moreover, if the one surviving original portrait of Anne features a symbolically initialled ‘B’ pendant – with B being for Boleyn, rather than A for Anne – it was very possibly ordered by her father, Thomas Boleyn, for his portrait gallery at Hever, where a later copy hangs today. In similar circumstances, Edward Seymour commissioned his own portrait of his sister Jane. Nor is it hard to imagine a plausible chain of ownership for such a survival – from Thomas Boleyn’s death in 1539 – through Anna of Cleves, who gained Hever Castle and its contents as a part of her divorce settlement in 15416 – to her executor, Henry Fitzalan, who had charge of her effects on Anna’s death in 1557 – to his son-in-law, John, Baron Lumley, who inherited Fitzalan’s paintings in 1580 and included a likeness of Anne Boleyn in his inventory of 1590.

It is known that Anna of Cleves personally occupied Hever Castle7 and would have been familiar with its paintings. If she had decided to sell a portrait of her disgraced predecessor by her countryman, Van Cleve – as a notable art collector, her friend Henry Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel would have been an obvious buyer. Alternatively, if she’d left the painting for his disposal as her executor, he’d surely have taken the opportunity to acquire it, having known Anne Boleyn personally and accompanied her to Calais in 1532. On Henry Fitzalan’s death, his art collection was merged with that of his son-in-law and heir, John, Baron Lumley,8 which a decade later certainly did include a portrait of Anne Boleyn.

The fact that the portrait in the Lumley Inventory of 1590 is described as ‘full-length’9 would not have made it unusual (Queens Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr were both painted full-length) or incompatible with other commissions for Joos van Cleve’s studio. We now know that the Lumley portrait was cut down at a later date; and if the rediscovered head-and-shoulders print is amalgamated with another three-quarter-length female portrait by Van Cleve (as below), some idea can be gained of how such a painting might originally have appeared.

Evidence in the following century suggests that from the Lumley collection the ‘full length Anne Boleyn’ passed back into royal ownership. It is less likely that it was hanging in Nonsuch Palace when Lord Lumley ‘remitted’ that residence to Elizabeth I in 1592, than that it was still in Lumley’s ownership when he died without heirs in 1609. In which event it may well have been purchased for his ‘New Lybrary Gallery’ at St James’s Palace by James I’s eldest son, Prince Henry Frederic, who is known to have acquired the Lumley collection of books and manuscripts and was an avid collector of renaissance paintings.10

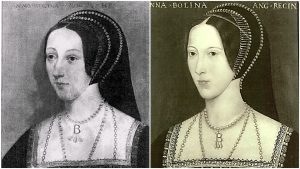

It is at about this time that copies of the likeness were made for inclusion in long gallery collections of kings and queens for numbers of aristocratic mansions – at least a dozen of which still survive, the widely reproduced National Portrait Gallery image among them. Many of these versions are clearly ‘copies of copies’, one or two of them quite crudely executed – and by comparison with the original, even the relatively sophisticated version purchased by Lord Astor for Hever Castle (below right) appears stiffly mechanical.

When Prince Henry Frederic died in 1612, his collection of books, manuscripts and paintings passed to his younger brother, Charles, to form a nucleus for his later collection; and the fact that this inheritance included the supposed Van Cleve portrait of Anne Boleyn is suggested by the information that Charles I commissioned the miniaturist, John Hoskins the Elder (1590-1665), to paint a miniature of Anne Boleyn ‘from an ancient original’,11 which by implication was in his ownership.

The miniature in the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry still survives, and (if one ignores the deliberately lightened hair-colouring) there is nothing to suggest from a comparison, that the ‘Van Cleve portrait’ and the ‘ancient original’ are not one and the same – although, as in every other comparison, the superior quality of the ‘Van Cleve’ version is immediately evident.

The original painting re-appears in the records approximately 150 years after the Hoskins copy was made; as ‘Lot 33’ in a sale catalogue for 1773, which identifies it as the ‘full length Anne Boleyn’ from the Lumley collection, subsequently cut down ‘due to damage by fire when in the Temple’.12 The question of how it reached the Temple from the collection of Charles I is complicated by the Cromwellian Interregnum; and although it’s possible that the King gifted or loaned the portrait to one of the Temple Halls (as a precedent, Elizabeth I presented royal portraits to the Middle Temple Hall), it’s more likely to owe its existence there to the Protector himself. Following the King’s execution in 1649, Cromwell is known to have awarded paintings to favoured individuals and establishments;13 and as a onetime student of Lincoln’s Inn himself, might feasibly have favoured the Inns of Court with items from the Royal Collection. Such an award would doubtless have caused embarrassment at the time of the Restoration in 1660, when Charles II repossessed as much of his father’s collection as possible. But the portrait still appears to have been somewhere in the Inner Temple at the time of the Fire of London in 1666, which is likely to have been when it was damaged. The fire spared the Middle Temple Hall. But according to Pepys, ‘a good part of the Temple burned,’14 and it’s recorded that the Inner Temple was destroyed.

The antiquary and collector of manuscripts, prints and paintings, James West, was called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1728,15 which one would suppose was when he saw the portrait of Anne Boleyn he was later to purchase – either in its fire-damaged state, or already cut down, repaired and re-framed. What is certain is that the picture remained in West’s collection until his death in 1772, when it was included that year in the sale of his paintings.

The purchaser of the painting at the West Sale in April 1772 remains unknown, and in the absence of an annotated catalogue must continue to do so. It’s recorded that Sir Joshua Reynolds bought paintings and that the collector Horace Walpole purchased many books and paintings from the West Sale for his new house at Strawberry Hill. But it’s apparent that a 1790 engraving of ‘Anne Bullen from the collection of the Hon. Horace Walpole at Strawberry Hill’16 was taken from the Hoskins miniature, which was by then in his ownership, rather than from the larger original painting. So clearly, he wasn’t the buyer.

The above represents an attempt to plot a likely route to survival for the portrait through the first 240 years of its existence, although its whereabouts for the remaining 240 years is still a mystery.

It is further significant that its sitter’s features, unlike those of other ‘workshop’ copies, bear close comparison with the Holbein ‘Anne Boleyn’ drawing in the British Museum, which has been and is still disputed as a likeness. With the ‘Van Cleve’ portrait reversed and the two images set side by side, the lines of forehead, cheek and chin appear virtually identical. The long, narrow jawline – also evident in portraits of Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth, and of her Howard and Carey relatives – is accentuated in the painting by the (invisibly narrow) ribbon which holds the French crépine head-dress in place. The shapes of the nose, mouth and brows, a little flattered in the painting, are essentially similar; while something indefinable in the expression of the dark eyes establishes a common likeness.

For the present, the whereabouts of the original ‘Van Cleve’ portrait is obscure. Indeed, it may well be lost to us forever. But the re-discovery of this print as a contemporary likeness of Queen Anne Boleyn, and its confirmation of the British Museum’s Holbein sketch as another, must surely be of immediate historical significance.

Notes and Sources

- Prof. E W Ives, Anne Boleyn, 1986.

- Guicciardini. Dedcrittione di tutti I Paesi Bassi, 1567.

- Peter van den Brink, Alice Taatgen & Heinrich Becker, Joos van Cleve, March 2011.

- Kunthistorisches Museum, Vienna & Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon.

- Calendar of Letters & State Papers between England & Spain, 1531-1533. p.525.

- Rymer’s Foedera, xiv. 709.

- Strickland, Vol 2, p 215: Letter from Anna of Cleves at Hever to Mary Tudor, Aug. 1553.

- King’s MSS xvii, A.ix.ff. British Museum, p.60-61.

- Roy Strong, Catalogue of Tudor & Jacobean Portraits, Anne Boleyn iconography, The Lumley Inventory.

- Roy Strong, Henry Prince of Wales and England’s Lost Renaissance. 1986.

- Early portrait miniatures in the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch, ed. C Holmes, 1917.

- Walpole Society, vi, 1918, p.21.

- The Sale of the Late King’s Goods, Dr Jerry Brotton, 2006.

- The Shorter Pepys, ed. Robert Latham, 1985.

- Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press.

- London Pub. Nov. 1st 1790, by E. Harding No. 132 Fleet Street.

Richard Masefield is a cousin of the poet, John Masefield, and a prizewinning author of historical fiction, with two Amazon Kindle bestsellers to his credit. His novels are recognised for their meticulous original research. To quote one of his recent blogs: ‘When I research my stories I am keen to share what I’ve learned with their readers – to explain for example how war horses were transported overseas to the crusades, how an entire underground city was excavated during the Great War, how nineteenth century tourists crossed the Alps on sledges, and why prostitutes of the period were frequently barren. I like to get the facts right, unpick the legends of the past and tell the truth as I perceive it.’

For more about Richard or to contact him directly, go to: http://www.richardmasefield.co.uk/.

Wow, I have to agree that if this is a true likeness of Anne which it certainly appears to be this should put to rest any doubts about the authenticity of the Holbien sketch. It also shows that though many of the paintings of her were made decades or more after her death they were based on fairly accurate descriptions of her.

I feel sorry for her ouch! It must hurt

Thank you for an interesting article. It would be wonderful if this could be authenticated and accepted because I have never believed the myth that every one of Anne’s portraits were destroyed. There is no contemporary evidence for such an event and it would not be the first time a family hid something which was then lost for centuries and refound in modern times. She has the classic Anne oval face, but so could other ladies. However, Anne would be painted just before her marriage, it made sense and fits with the times.

Trying to sort out the identities of subjects in paintings and drawings well after the fact is always a challenge. Still, it is intriguing to follow the estimations and comparisons given above. It sounds plausible and there seems to be resemblance, so perhaps this is a rediscovered portrait of Ann Boleyn.

How was the print “re-discovered”?

Also was it compared to the Holbein sketch in the Windsor Castle collection with Anne wearing a cap and fur trimmed night “gown”? That sketch has a stronger attribution as an authentic contemporary image of Anne.

The print was discovered in an old biography of Henry VIII, and also appears (differently cropped) in a collection of supposed images of Anne Boleyn on Alison Weir’s website. It would be good to know where the original is held – and also of course if a painting survives. The features in this image DO bear comparison with the Windsor Castle sketch – although in my view the supposed ‘Joos van Cleve’ image gives a better idea of the subject as she would have looked in her prime. RICHARD MASEFIELD

I can shed some light in this ‘ANNA BOLINA UXOR 2 HVIII’ image.

It was reproduced most recently in ‘Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies’ (by Mark C. Carnes) published in 1995. The image was licensed from the Bettmann Archives. About a year ago, I had contacted Bettmann about this picture, but never received an answer.

From what I remember, I had first noticed this likeness of Anne Boleyn in a Henry VIII book in my high school. The book even gave the name of the painter, though I don’t recall it unfortunately. The name was English and ‘modern’ sounding if I can say that.

That said, this painting/print is likely 19th or early 20th century. It is not Tudor. That explains why Anne is slightly glamorised and appears more life-like than the ‘mechanical’ late 16th/early 17th century versions of this picture.

I believe it is a modern reinterpretation of a specific variant of the ‘B’ pendant type portrait which shows Anne looking upwards – perhaps the very version owned by Lyndhurst Mansion in New York:

https://tudorfaces.blogspot.ca/2016/08/anne-boleyn-at-lyndhurst-mansion-new.html

http://nthpcollections.tumblr.com/post/91158099332/portrait-of-anne-boleyn-purchased-by-anna-gould

The Bettmann Archives link is interesting, and certainly worth following up. In my view the image does not have the appearance either of a deliberately flattering portrait or a ‘modern interpretation’ – but does correspond in style and background to a number of contemporary Joos van Cleve portraits. It also includes details in the crepine head-dress, positioning of the (invisible) chin strap which do not appear in other ‘workshop’ copies and look authentic.

Then again, all views are welcome. New identifications are always hard to authenticate!

The American portrait purchased by Anna Gould does look a good deal more like the ‘Van Cleve’ print than many other long gallery versions. But it’s also fairly crudely painted, suggesting that it’s a copy (or a copy of a copy) of the original.

I can see such a resemblance in this print to the portrait of Elizabeth as a teenager. The look in the eyes and the expression. Not very scientific i know, but the likeness sells the possibility for me.

the holbein drawing shows a woman of intelligence. he captured the eyes so well, in his portraits.

Fascinating article, and hugely frustrating that the trail goes cold…. it would be interesting to compare the image with that of the “Moost Happi” medal (of course, that only totally authenticed likeness of Anne Boleyn made in her lifetime) and also the excellent recent reconstruction work done by Lucy Churchill. Speaking for myself I remain unconvinced that the British Museum sketch is of Anne Boleyn. As others will remember, this item became detached from others in the Holbein collection, and the identification appears first to have been made in the seventeenth century. The drawing in the Royal Collection seems a more likely candidate, and of course that identification is complicated by the coat of arms on the back…. like so much relating to Anne Boleyn, so many tantalising, but ultimately inconclusive, clues….

The feature on the contemporary ‘Most Happi’ medal which is least damaged, the long narrow jaw, does correspond closely to the ‘Van Cleve’ print and other long gallery copies. Some convincing work has been done to show that the features in the two Holbein sketches are basically very similar, although at first sight the lowered chin and ‘rubbed’ eyebrows in the Windsor sketch are distracting. Perhaps it’s worth adding that the ‘Van Cleve’ print was exhibited as ‘a rare portrait’ of Henry VIII’s second queen at the Alexander Palace Time Machine Forum Discussion in Jan. 2006.

Please could you point me in the direction of the work that has been done to compare the features in the two Holbein portraits? I have just been looking again at both of them, and really don’t think they are of the same woman – although such perceptions are, of course always going to be subjective. The Wyatt coat of arms on the back of the Windsor sketch is of course a complicating factor. Although I know the Royal Collection have removed the question mark from their identification, I personally suspect neither of them is Anne Boleyn!

The noses in the two portraits are different which has always bothered me.

See ‘Comparison of Holbein sketches alleged to be of Anne Boleyn’ – work undertaken by David Starkey and Bendor Grosvenor.

I find this print closely resembles the John Hoskins miniature of Anne.

Anne Boleyn had a double chin in all of these portraits. I find that rather endearing and makes her more real.

Yes, me too, although I think we all have a double chin if we hold our face in that position – well, I do anyway!

In the fourth paragraph from the end, at “But it’s apparent that a 1790 engraving of ‘Anne Bullen from the collection of the Hon. Horace Walpole at Strawberry Hill’16” is footnote number “16” but Notes and Sources lists only 15. Could that 16th reference be given?

I will check, thank you.

I hadn’t separated 15 and 16 properly, so 15 is Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press and 16 is London Pub. Nov. 1st 1790, by E. Harding No. 132 Fleet Street.

Sorry about that and thank you for alerting me.

You are quite welcome and thank you for finding and giving the reference.

The image also bears close comparison with the Horenbolte Miniature in Royal Ontario Museum.

I don’t think I need a portrait of Anne to know what she looked like look to the pics of her daughter and the portrait in queen Elizabeths ring and you get a good idea what she looked like a bit like Elizabeth but darker I’m not sure anyone can trust all these portraits that keep popping up 400 years is a long time

The NPG portrait dates to Elizabeth I’s reign so I would assume it was a pretty good likeness being in living memory. There would have been plenty of people at court who would have known what she looked like. Unfortunately, we don’t know for sure that the locket image is Anne. I believe it is, but others have argued that it is a younger Elizabeth or Catherine Parr. The only contemporary images we have of Anne are the 1534 medal and the crude drawing on her coronation banquet table plan.

Although skilfully painted, the NPG portrait is one of the least accurate copies of the type (and this identification as contemporary is all about detail). For the record, the NPG version shows a misunderstanding of the way the crepine head-dress was worn and secured and omits the muslin veil across the hair altogether.

But it is Elizabethan, nevertheless, as the NPG dated it to the late 16th century based on analysis of the technique, materials and dendrochronological analysis. I’ve done a lot of research on costume of the time and can’t see anything wrong with the French hood in the portrait, the veil is there. It’s worn in the same way as in the Hoskins miniature and the marriage portrait of Mary Tudor and Charles Brandon. Are we talking about the same portrait? – see http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitConservation/mw00142/Anne-Boleyn.

Claire – yes we are talking about the same portrait. In the more detailed (accurate) copies a fine muslin veil appears across the back parting of the hair, also the black lower lappet of the crepine head-dress is aligned with the angle of the jaw (because a fine ribbon, partially visible in some portraits of other ladies with crepines, was looped under the jaw to hold the head-dress in place). Neither is correct in the NPG version.

i think its probably a copy of a portrait thats been around its maybe not that old

Fascinating. I know very little about art, but I have seen the one portrait…Holbein, I think, identified as Mary or Margaret Shelton. Can’t remember where I saw it labelled as such…I’ll see if I can find. I would so love to know what she looked like for sure…I think Elizabeth’s early portraits give us our best clues. Thank you!

The Holbein sketch sometimes identified as Margaret Shelton is the Windsor Castle drawing – possibly of Anne during confinement before Elizabeth’s birth?

Anne, do you mean the Holbein sketch labelled Lady Henegham (Heveningham)? This one – https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/912227/mary-lady-heveningham-151015-157071. Lady Heveningham being daughter of Sir John Shelton.

the holbein portraits are all so life like and this one compares to his work – because of the realism. it would be interesting to know about the painter of this portrait under discussion.

Oh it’s beautiful! I feel like we’re a split second away from her turning her head to speak to us. I can believe this is her and I see a family resemblance with the Katherine Howard portrait. I’ve been praying for lost pictures of her to show up. I’ve always thought there must have been someone brave and sane enough to “lose” her images and maybe some of her belongings so they could be found later. This is an emotional post, yes–I’m mooost happy to see her 🙂

Ouch! I was so excited I forgot to say thank you for sharing this!

Oh same Maybeth. There is a little sparkle in her eyes which indeed are “black and beautiful”. Her graceful neck and lips with that tiny upward tilt are beautiful.

I would be thrilled to think this was her!!

Curiously enough iv always thought the NPG portrait is the the one that shows the strongest likeness to her daughter Queen Elizabeth, but her forehead is quite high and in other portraits including this latest one it’s much lower. Has anyone ever noticed her sleeves, they look beautiful with the dark wine red colour fur ?

I managed to get 2 new screen captures of the Anne Boleyn portrait at Lyndhurst Mansion in New York. Please click on the images for a close-up.

See: https://tudorfaces.blogspot.ca/2016/08/anne-boleyn-at-lyndhurst-mansion-new.html

The inscription reads ‘ANNA REGINA UXOR 2 H8’ which is actually the same as that which appears in the images Mr. Masefield had put up. It is actually not ‘ANNA BOLINA UXOR 2 HVIII’ . That is a misreading.

Because of the similarities in the sitter and in the inscription itself, I’m wondering if the image Mr. Masefield submitted is of an early 20th century photograph of the Lyndhurst portrait itself. Alternatively, the photo may be of a ‘modern’ reworking of the Lyndhurst picture as I had mentioned before.

Quality-wise, the Lyndhurst painting is no different from the various formulaic ‘B’ pendant pictures of Anne done in the Elizabethan and early Jacobean periods. It is similar to the Windsor Castle version which also has a red cushion with gold embroidery at the bottom. The lost original was unlikely the work of Joos van Cleve, but probably Lucas Horenbout/Horenbolte, as explained here:

https://tudorfaces.blogspot.ca/2015/01/a-reassessment-of-queen-anne-boleyns.html

Thanks for the additional shots of the Lydhurst painting (although I do think one of the earlier links you provided gives a slightly better idea of its quality). The pose, as you have pointed out, is virtually identical to that of the portrait I’ve identified. But to my mind it is the Lydhurst painting that appears the cruder of the two, and is therefore perhaps a copy of the original. Of all the numerous crepine/B necklace copies, I still maintain that the ‘Van Cleeve’ version is demonstrably the liveliest and most natural. It really doesn’t look like a modern copy. But of course I accept that others may not feel the same way.

Richard, I have never looked at a portrait of Anne that I thought captured the mysterious charm and sparkle that she surely possessed. Until now!!!

That beautiful straight gaze, graceful neck and the smallest of upward tilts to her mouth. If this is her likeness she indeed must have been fascinating. It always astounds me that we are so passionately interested in this lady after nearly 500 years.

Thanks for sharing.

Ver interesting article and follow up. In the catalogue of the 1953 RA exhibition’ Kings’s and Queens’, the portrait of Anne Boleyn then belonging to Mrs Radclyffe now at Hever is quite different to how it is today. The picture has obviously been very over cleaned since 1953, as the nose has a bump in it, and a round bulbous end, akin to the picture in the NPG. the mouth is fuller and so are the eyelids, even the fingernails are slightly different. She is actually less attractive to modern eyes. The figure of Anne in Madame Tussaud’s was sculpted from the drawing in the BM and is quite brilliant. If the BM drawing is Anne, then then the 2 miniatures by Lucas Hornebolte (Ontario and Buccleugh collections) could very well be the same person. As a portrait painter, and you only have to look at portraits of the present Queen to see that , every artist sees it’s sitter differently. Look at the difference in all the portraits of Elizabeth I’st, in some she has a hooked nose, in Hilliard’s she doesn’t and we know she sat for the first, There are only 4 portraits of E 1 where the nose is the same , as a girl in the Windsor portrait, the drawing by Zuccaro, the Reading portrait and the unfinished Oliver miniature in the V&A. My old art master did 6 official copies of the state portrait of Elizabeth II by Sir James Gunn, there are about 35 of them around the world in embassy’s etc. And some are very bad. There is even a very poor copy in the public entrance to Buckingham Palace.

I somehow want this to be an authentic likeness of her. It combines all the features of the later portraits and descriptions and I find it very charming. Not a scientific judgement, but it simply fits my personal image of Anne.

Can anyone name literature about the picture in the ring which belonged to Elizabeth? I have always believed it to be Anne (according to f.ex. Eric Ives), but just recently stumbled upon a comment which disputed the attribution, claiming it could be Catherine Parr as well. Of course I don’t remember where I read this, but I’d like to find out more about it.

I think Susan James in her book on Catherine Parr argues for it being Catherine. I think the costume looks 1530s though.

Thank you! I agree, it looks more like Anne to me. The facial features, especially the nose, fit as well.

I say why not in this day and age with 3d technology and retrieve the bones from the Chapel in the tower of London , and do facial reconstruction like they did of most recent with Richard who was found in a carpark .it makes more sense to use the technology we have today ,that indeed if they are Anne boleyn bones . all of course done with the greatest care and respect. at least we will have then a true depliction of how she truly looked with constant speculation.

I find it interesting that if this was not cropped it would match up very well to Henry’s portrait, they would have similar proportions and be facing each other, which supports the idea of them having commemorative matching portraits made in Calais.