On 12th February 1554, Lady Jane Grey and her husband, Guildford Dudley, were executed. Guildford was beheaded on Tower Hill and Jane was beheaded withing the walls of the Tower of London. Jane was sixteen years old and Guildford was around 18/19 years old.

On 12th February 1554, Lady Jane Grey and her husband, Guildford Dudley, were executed. Guildford was beheaded on Tower Hill and Jane was beheaded withing the walls of the Tower of London. Jane was sixteen years old and Guildford was around 18/19 years old.

You can read all about their executions in my previous posts:

- 12 February 1554 – The Executions of Lady Jane Grey and Lord Guildford Dudley

- Lady Jane Grey’s Execution

- The Trial of Lady Jane Grey – 13th November 1553

But today I’d like to remember the courage of Jane and Guildford as they faced death, rather than thinking about the tragedy of their deaths. I’m a committed Christian and I’d like to think that I would stand up for my faith and die for it, if needs be, but here are two teenagers who went to their deaths with courage, faith and dignity.

Guildford and Jane had been found guilty of high treason at a trial on 13th November 1553 and sentenced to death. They were charged with taking possession of the Tower of London, proclaiming Jane as Queen and Jane for “signing various writings” as queen. They and their families had acted on Edward VI’s “devise for the succession”, in which he named Jane as the heir to the throne, but Edward’s half-sister, Mary, had challenged Jane and won. Jane was deemed a usurper and traitor. Their executions were scheduled for 9th February 1554, but extra time was given for Dr John Feckenham, Mary I’s Chaplain and Confessor, to try and save Jane’s soul by persuading her to recant her Protestant faith and return to the Catholic fold. Jane refused and stuck to her faith, spending her last days writing a treatise which Guildford added a prayer to.1

Little is known of Guildford’s feelings during those last days, but it appears that he too kept his faith. He was led out to the scaffold site on Tower Hill at 10am on the 12th February. The fact that no priest accompanied him suggests that he refused one and that he “remained staunch to reform”.2 On the scaffold, Guildford addressed the crowd briefly and then got down on his knees and prayed “holding up his eyes and hands to God many times”. After asking the crowd to pray for him, he put his neck on the block and the executioner beheaded him with a single blow of the axe. Eric Ives quotes Richard Grafton, who very probably had known Guildford, recalling ten years later that “even those that never before the time of his execution saw him, did with lamentable tears bewail his death.”3

A beautiful carving in the stone wall of the Beauchamp Tower is a reminder of Guildford Dudley, his fathers and brothers, who were all imprisoned there in 1553 following Lady Jane Grey’s fall. It is thought to have been made by Guildford’s brother, John, or someone at his command, and it features the bear and ragged staff (the badge of the Earls of Warwick) and the double-tailed lion rampant (the badge of the Dudley family). It also features a floral border with oak leaves and acorns for Robert Dudley (quercus robur is the Latin for English oak), roses for Ambrose Dudley, honeysuckle for Henry Dudley (lonicera henryi) and gillyflowers for Guildford Dudley. The inscription reads:

“You that these beasts do wel behold and se, may deme with ease wherefore here made they be, with borders eke within [there may be found] 4 brothers names who list to search the ground.”

After Guildford’s execution, Lady Jane Grey was led out to the scaffold on Tower Green. She addressed the waiting crowd:

“Good people, I am come hither to die, and by a law I am condemned to the same; the fact indeed against the Queen’s Highness was unlawful and the consenting thereunto by me: but touching the procurement and desire thereof by me or on my behalf, I do wash my hands thereof in innocency before the face of God and the face of you good Christian people this day.

I pray you all good Christian people to bear me witness that I die a true Christian woman and that I do look to be saved by no other mean, but only by the mercy of God, in the merits of the blood of his only son Jesus Christ. I confess when I did know the word of God I neglected the same and loved myself and the world, and therefore this plague or punishment is happily and worthily [deservedly] happened unto me for my sins. I thank God of his goodness that he has given me a time and respite to repent.

Now good people, I pray you to assist me with your prayers. Now good people, while I am alive, I pray you to assist me with your prayers.”4

Eric Ives writes of how, in her speech, Jane was emphasising that she was saved by faith alone, the doctrine of justification by faith, and that she did not need prayers after her death. In her few minutes on Earth, she was remaining true to her reformist faith.5

After her speech, Jane knelt and said Psalm 51, the Misere, in English, “Have mercy upon me O God, after they great goodness: according to the multitude of thy mercies, do away mine offences”. She then embraced John Feckenham, the man who had been sent to Jane to try and persuade her to recant, and said to him “Go and may God satisfy every wish of yours”.6 Jane then gave her handkerchief and gloves to Elizabeth Tilney, and her prayer book to Thomas Brydges, the deputy lieutenant of the Tower, who had been charged with passing it on to her father. She then removed her gown, headdress and collar. After forgiving the executioner and begging him “despatch me quickly”, Jane knelt at the block, tossing her hair forward and out of the way, and putting on the blindfold. It was then that she lost her composure and panicked, “What shall I do? Where is it?”. A bystander guided Jane to the block where she lay her neck, praying “Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit.” She was then beheaded with one blow of the axe.

I love historian Leanda de Lisle’s view of Lady Jane Grey as “a Protestant Joan of Arc, calling up fresh troops to fight against Mary Tudor while her own generals betrayed her”,7 and that’s how I’ll be remembering her today, as a courageous young woman who saw being queen as God’s will and who kept true to her God right to the end. I’ll also remember her husband who kept true to his faith and his wife.

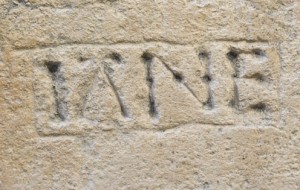

There is a carving in the stone of the Beauchamp Tower related to Jane too. It is simply the word “Jane”, or “IANE” as it is written, with a simple rectangular border. It is unlikely that it was carved by Jane, because she was imprisoned “in a small house next to the royal apartments”, but it may have been carved by Guildford or one of his family.

Notes and Sources

- Wilson, Derek (2005) The Uncrowned Kings of England, Robinson, p238

- Ives, Eric (2009) Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery, Wiley Blackwell, p275

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p276-277

- Ibid., p276, quoting from “Here in this Booke”

- Ibid, p277, quoting Giovanni Francesco Commendone, “The Accession, Coronation and Marriage of Mary Tudor”

- De Lisle, Leanda (2008) The Sisters Who Would Be Queen, Ballantine, p286