My work is all about banishing myths and using primary source evidence to try and get to the truth about the Boleyns and the times they lived in. Anyone who has studied history will know that our perceptions of historical personalities, their reputations, can be far removed from who those people really were. We are affected by fictional portrayals, films and TV series, the differing opinions of historians and authors…

Even if we stick to primary sources, we then have to consider people’s bias and figure out what’s historical fact and what’s propaganda. Historians have to interpret sources and two people can look at the same source and interpret it completely differently – studying and researching history is a real minefield!

One person who has been given a bad historical reputation is Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire and Ormond, father of Anne Boleyn. Here was a man who was highly intelligent, who was a loyal servant to Henry VII and Henry VIII, and whose incredible career and rise to favour started long before the King had laid eyes on either of his daughter.

Is he known for his skill as an ambassador or being the best French speaker at Henry VIII’s court? Is he known for the opportunities he gave Anne Boleyn by securing a place for her at Margaret of Austria’s court?

No. Instead, he has gone down in history as a greedy, manipulative, over-ambitious man who pimped out his daughters to the King in return for wealth and advancement.

I’ve been researching the Boleyns for over four years now and I’ve not found a trace of the manipulative pimp Thomas Boleyn in the records. It is thought that Mary Boleyn caught the King’s eye around 1522, but Thomas Boleyn was already a high-flier at court by then, he had no need to push his daughter into the King’s bed. Here are some of his early career highlights:

- 1497 – Along with his father, Thomas fought on the King’s side against the rebels of the Cornish Rebellion.

- 1501 – He was present at the wedding of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon.

- 1503 – He was chosen by Henry VII to accompany his eldest daughter, Margaret Tudor, to Scotland, to marry James IV.

- 1509 – When Henry VIII came to the throne Thomas became an Esquire of the Body and was then made a Knight of the Bath at his coronation.

- Early years of Henry VIII’s reign – Thomas was given various offices including keeper of the exchange at Calais and the foreign exchange in England, joint governor of Norwich Castle with Sir Henry Wyatt, Sheriff of Kent several times and also served on commissions of the peace.

- 1511 – Thomas was involved in the jousts to celebrate birth of Prince Henry, Duke of Cornwall. He was also a chief mourner and one of the knight bearers at Prince Henry’s funeral on the 27th February.

- 1512-1513 – He was sent to the court of Margaret of Austria, with John Young and Sir Robert Wingfield, to act as an envoy to her father, Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, to conclude an alliance between England and the Empire against France. Thomas Boleyn became so friendly with Margaret that they had a wager on how long the negotiations would take and he also secured a place for his daughter, Anne, at Margaret’s court. A place in Margaret’s court was highly sought after by royal and noble families in Europe so this showed just how much Margaret respected Thomas.

- 1514 – Thomas Boleyn secured places for both his daughters in the entourage of Mary Tudor, who was going to France to marry Louis XII.

- 1516 – He was a canopy bearer at Princess Mary’s christening.

- 1517 – He was entrusted with looking after Margaret Tudor on her visit to England.

- 1517 – He acted as Queen Margaret of Scotland’s official carver for the forty days of her visit to England.

- 1518 – Thomas was a member of the Privy Council by this time and was involved in the negotiations for the Treaty of Universal Peace signed that October.

- End 1518/beginning of 1519 – Thomas was appointed as the English ambassador to the French court. He served there as Henry VIII’s ambassador and as Cardinal Wolsey’s agent. While in France, Thomas became good friends with the French royal family.

- 5th June 1519 – Thomas sponsored Francis I’s baby son, Henry, Duke of Orleans, in the name of Henry VIII.

- 1520 – Returns to England and is appointed Comptroller of the Household.

- 1520 – Thomas attended the Field of Cloth of Gold, having been chosen as one of 40 select members of government, nobility and the Church who were to ride with the King to his first meeting with Francis I. Thomas’s wife, Elizabeth, was appointed to attend Queen Catherine.

- May 1521 – Thomas was now the Treasurer of the Household and was also was appointed to the special commissions of oyer and terminer which tried Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. He benefited from Buckingham’s fall, being granted in survivorship the manor, honour and town of Tunbridge, the manors of Brasted and Penshurst, plus the parks of Penshurst, Northleigh, and Northlands, in Kent. He had also recently been granted the manor of Fobbing in Essex and Fritwell in Oxfordshire. His manors now totalled around two dozen.

- 1521 – Thomas accompanied Cardinal Wolsey to meet Margaret of Austria under the pretence of mediating between France and the Empire, but actually to secure an alliance between England and the Empire.

All that before either of his daughters became involved with the King.

There is no way of knowing how Thomas felt about his daughters’ relationships with the King. We cannot get inside his head and we don’t have a journal or letters in which he expressed his feelings, but, as I explained in my article In Defence of Thomas Boleyn the evidence actually points to Thomas being unhappy about their relationships. When Mary Boleyn was widowed after William Carey died from sweating sickness, the King had to intervene and ask Thomas to provide for her financially. This suggests that there was not a close relationship between father and daughter at this time. As far as Anne’s relationship with Henry is concerned, Chapuys recorded in February 1533 Thomas Boleyn’s opposition to the marriage:

“I must add that the said earl of Wiltshire has never declared himself up to this moment; on the contrary, he has hitherto, as the duke of Norfolk has frequently told me, tried to dissuade the King rather than otherwise from the marriage.”1

and in May 1533, he recorded Anne’s indignation at the opposition of her father and uncle:

“Shortly after the Duke began to excuse himself and say that he had not been either the originator or promoter of this second marriage, but, on the contrary, had always been opposed to it, and tried to dissuade the King therefrom. Had it not been for him and for the father of the Lady, who feigned to be attacked by frenzy to have the better means of opposing it, the marriage would have been secretly contracted a year ago; and for this opposition (the Duke observed) the Lady had been exceedingly indignant with the one and the other.”2

Whatever Thomas’ feelings about Anne’s marriage, he certainly did not need it to happen for his career to flourish. By this time, he was Lord Privy Seal and the Earl of Wiltshire and Ormond.

As well as being a royal favourite, a trusted adviser and a gifted diplomat, Thomas Boleyn was also a patron of humanism and a reformer. Maria Dowling3 writes of how a humanist scholar, Gerard Phrysius, was in the service of Thomas Boleyn between 1529 and 1533, and he was also the patron of Robert Wakefield, who taught Hebrew at Cambridge, as well as Thomas Cranmer and John Baker. He kept in touch with French reformers like Clément Marot, the French poet, and he supported his godson Thomas Tebold,4 later known as one of Cromwell’s continental agents, in his travels around Europe in 1535 and 1536. Tebold spread the news that Thomas was a patron of the New Learning and New Religion, and reported back to Thomas on the Inquisition in Europe. Three of Tebold’s letters5 to Thomas are still in existence and in one he refers to sending an epistle by Marot, “who has fled from France for the Gospel”. The two men corresponded through Reyner Wolf, a Dutch printer and bookseller who ran a shop in St Paul’s, London. In my research into Wolf, I found out that Wolf travelled annually to the Frankfurt am Main book mart which allowed him to work as an agent for the English government. In 1536 he conveyed a message from the Swiss reformer Heinrich Bullinger to Cranmer and in 1539 he carried messages from Henry VIII to Christopher Mount, an agent in Germany. Some historians have argued that Thomas Boleyn was a conservative Catholic and opposed George and Anne’s religious beliefs, but I cannot see why he would support Tebold and read reformist works if this was the case.

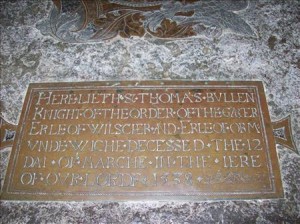

So, today on the anniversary of Thomas Boleyn’s death in 1539 I’d like to banish the mythical Thomas Boleyn and remember him the way his servant Robert Cranwell did, as “a good Christian man”,6 and as a gifted and loyal courtier. RIP Thomas Boleyn, husband, father, ambassador, reformer and earl.

Sources

- Span. Cal. iv. ii.1048

- Span. Cal. iv. ii.1077

- Dowling, Maria, Humanism in the Age of Henry VIII

- Tebold is listed as godson of Thomas Boleyn in an Index of Kent wills – http://vulpeculox.net/history/willst.htm

- LP viii.33, LP iv.6304, LP x.458 12

- LP iv. Part 1. 511