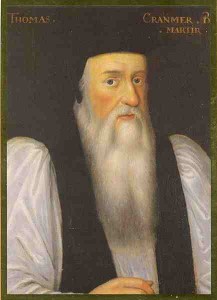

Today I will be remembering Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was burned at the stake on 21st March 1556 after being found guilty of heresy and treason.

Today I will be remembering Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was burned at the stake on 21st March 1556 after being found guilty of heresy and treason.

Martyrologist John Foxe recorded his execution in his Book of Martyrs:

“With thoughts intent upon a far higher object than the empty threats of man, he reached the spot dyed with the blood of Ridley and Latimer. There he knelt for a short time in earnest devotion, and then arose, that he might undress and prepare for the fire.

Two friars who had been parties in prevailing upon him to abjure, now endeavoured to draw him off again from the truth, but he was steadfast and immoveable in what he had just professed, and before publicly taught. A chain was provided to bind him to the stake, and after it had tightly encircled him, fire was put to the fuel, and the flames began soon to ascend. Then were the glorious sentiments of the martyr made manifest;—then it was, that stretching out his right hand, he held it unshrinkingly in the fire till it was burnt to a cinder, even before his body was injured, frequently exclaiming, “This unworthy right hand!” Apparently insensible of pain, with a countenance of venerable resignation, and eyes directed to Him for whose cause he suffered, he continued, like St. Stephen, to say, “Lord Jesus receive my spirit!” till the fury of the flames terminated his powers of utterance and existence. He closed a life of high sublunary elevation, of constant uneasiness, and of glorious martyrdom, on March 21, 1556.”

Cranmer had stretched out his right hand into the fire to punish it for signing the recantations he had submitted to Mary I in an effort to save himself. On the day of his execution Cranmer had been told to make a final public recantation at the University Church, Oxford. Instead, after saying the expected prayer and exhortation to obey the King and Queen, he renounced his previous recantations, saying:

“And now I come to the great thing which so much troubleth my conscience, more than any thing that ever I did or said in my whole life, and that is the setting abroad of a writing contrary to the truth, which now here I renounce and refuse, as things written with my hand contrary to the truth which I thought in my heart, and written for fear of death, and to save my life, if it might be; and that is, all such bills or papers which I have written or signed with my hand since my degradation, wherein I have written many things untrue. And forasmuch as my hand hath offended, writing contrary to my heart, therefore my hand shall first be punished; for when I come to the fire, it shall first be burned.

And as for the Pope, I refuse him as Christ’s enemy, and antichrist, with all his false doctrine.

And as for the sacrament, I believe as I have taught in my book against the bishop of Winchester, which my book teacheth so true a doctrine of the sacrament, that it shall stand in the last day before the judgment of God, where the papistical doctrines contrary thereto shall be ashamed to show their face.”

Thomas Cranmer is known as one of the “Oxford Martyrs”, together with his friends and colleagues Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, who were executed for heresy on 16th October 1555. Martyrs’ Memorial, at the end of St Giles Street, reminds visitors to Oxford of these three courageous men. The inscription on the memorial reads:

“To the Glory of God, and in grateful commemoration of His servants, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Prelates of the Church of England, who near this spot yielded their bodies to be burned, bearing witness to the sacred truths which they had affirmed and maintained against the errors of the Church of Rome, and rejoicing that to them it was given not only to believe in Christ, but also to suffer for His sake; this monument was erected by public subscription in the year of our Lord God, MDCCCXLI.”

A cross of cobblestones has been set into the road in Broad Street, marking the place of execution.

You can read more about Cranmer’s life and his link to Anne Boleyn in my article The Life of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and you can read more about his arrest, imprisonment and execution in my article The Unlawful Execution of Thomas Cranmer.

An excellent book on Cranmer is Thomas Cranmer: A Life by Diarmaid MacCulloch.

Notes and Sources

- Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, p236, Chapter on Archbishop Cranmer

I’m somewhat aware of what happened to Thomas Cranmer as I have read a few books which have included a few details of his life. However reading this post has reduced me to tears. I don’t know maybe it’s a womanly thing but I cried like a baby placing myself there hearing his words with my own ears and seeing his fate. Such detail. Great post. Thank you. I am so very glad to have found this site. I have learned so much. I have already ordered a book about him. I want to know more.

Thank you, I’m so glad that you were moved by my post, he was a great man.

As a Catholic myself, I deplore the treatment of this brave Protestant martyr and I too have been reduced to tears reading this post. I thank God that nobody now (at least no right thinking person) considers it a fitting act of faith to burn or butcher someone on the grounds of religious differences.

I hope that Cardinal Nichols doesn’t excommunicate me for this, but some of what the Reformation martyrs said about abuse and corruption in the Church certainly has me nodding sadly.

Whether or not Cranmer would have wished it, I pray for the repose of his soul.

I think there will always be corruption and abuse of positions in the Church because people are flawed, but I would hope that there are more people fighting it than adding to it. I’m not a Catholic but the present Pope appears to be a lovely man, a real man of God and also of the people.

I think the ways in which Cranmer’s views changed over time can shed some light on what Anne’s views might have been and on the arguments about whether she was (or wasn’t) an evangelical or proto-protestant.

For example, what Cranmer said about the sacrament in his “book against the bishop of Winchester”, and believed at the time of his death, is quite different from what he believed in 1536 when the 4th of the Ten Articles affirmed the real, substantial, and corporal presence of Christ’s body and blood in the bread and wine. (That doesn’t necessarily, btw, mean transubstantiation. There are other ideas of real presence, such as the Lutheran one.)

As I’ve just written in a comment on the “Life of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer” post, where I also quote most of the 4th Article re the sacrament (if anyone wants to see what it says), I think there’s a tendency to over-simplify and to see things through the lens of later developments, so that anything that seems traditionally Catholic in Anne’s words or behaviour is taken as meaning that she wasn’t really reformist, evangelical, or proto-protestant at all. There were a great variety of different views in those years, and a great variety of different ways of mixing and combining positions on different issues; and when it took even someone like Cranmer many years to think some things through and become more clearly protestant, it shouldn’t be thought that Anne wasn’t reformist if she didn’t rapidly and completely break with the past in all the ways that the reformation eventually brought about.

Did you know that Archbishop Thomas Cranmer made four recantations? Each is longer and more detailed than before and speaks to the fact that the authorities wanted the world to be certain that this brave man in particular had denied his faith. I can understand the government wanting to make things difficult for Cranmer; Mary saw him as the prime mover in her parents divorce and the humiliation of her and her mother. She also saw him as instrumental in the many chnages that had followed. I am not sure that her assessment is absolutely fair; although Cranmer had come up with the way for Henry to have his marriage to Catherine annulled and announced it as such; he did go through the legal process that was available in England at that time. He was also introduced to Henry by Cromwell and ordered by the King to make it so. He was appointed Archbishop by the King and approved by the Pope; but his work from then on was his own. Much of the prayer book that exists in England and the communion was introduced by Cranmer, although it was changed in 1572 and 1662, and 1922 with elements of the original in tact. I actually, although a Catholic like the Book of Common Prayer. I have also been to services from 1549, which are held by the Prayer Book Society to recall the work of Thomas Cranmer. I also believe that he was a man who was genuine in his work and beliefs and a sensitive person.

However, Mary saw him as an enemy and in fact he would have been executed for treason as well as heresy in her eyes. Some people have wondered why he was executed after he had recanted when the normal thing to do would to have put him in prison or done penance instead. I think the state needed to send a message with the death of Cranmer. Mary believed that she had to make an example of him and may have wanted personal revenge. I do not believe that Mary was an evil or a person who sought death of people just for the sake of it; she believed that Cranmer was a genuine threat to her and her legitimacy. And that I think is the crux of the matter; Mary had reversed the legislation that declared herself a bastard and taken the status of the church essentially back to 1529; the events that happened had been wipped from history! Cranmer was given several chances to convert and to repent; he did so when he saw that he had no longer a choice. I think that he was under no illusion that his recantations were to be used for any other purpose than propaganda and he accepted that he was still going to die. It is recorded that he burnt first his hand that had made the singnatures; he had not been sincere in his recantations and Mary and her government must have believed they had been correct to execute him, seeing him as condemned by his own words and actions. But I agree that he was a brave man.

Cranmer was taken to the main church and placed in a huge pulpit on a raised platform and made to declare his so called crimes and sins before a large gathered crowd. That in itself must have been terrifying. Imagine the shouting, the booing, the chanting, the interruptions, the cries of both sympathy and derision, the officials calling on him to speak up and declare his crimes and recant, the well wishers shouting out words to encourage him in his ordeal; to even stand there and with any dignity at all make his forced speech was brave in itself. The four documents were to ensure that he did not go back on anything and each time he had to make it in public. I have seen the place, the marks on the pillor were the platform was errected and the pulpit placed for him to make this famous declaration. It was quite moving as is anything to do with these brave men and women of either side of the faith.

I recently went to Chester and visited Boughton the village just outside that George Marsh was executed in 1555. There is a monument, not as grand as the one in Oxford but one that was placed there in the 1870’s, a stella marking the execution spot, with his name and dedication on. It is at the side of the road, few people actually are aware it is there, but it overlooks the sands and marshes and the area looks as if it has been lost in time. It is now not a small village, but an outer district of Chester and accessible by bus and public transport, but at the time it was remote and there was a small church and a leper hospital and cemetary, which he was also connected with. Here he also served and gave aid to many local people. Ironically in 1679 a Roman Catholic martyr was also killed near this same spot for a trumped up plot against Charles II and Blessed John Plessington’s name was added in 1980. I believe all the men and women killed for religious or political reasons during these two terrible centuries of madness and terror were brave and should be honoured.

Mary for some reason chose to allow Cranmer to be executed for heretical beliefs rather than treason, when either in the eyse of the state could have been proven, but whether he died in this terrible way, by fire or the more dreadful death of hanging,drawing and quartering, he is still a brave man who deserves to be honoured as a martyr and a man of principle. While I can understand the position of Mary and her government in most of these cases; I think that in the case of Thomas Cranmer she had a personal stake and whether guilty of anything other than religious differences in state terms or not; it was a certainty that he was going to be executed as he was seen as too much of a threat to keep alive. His trial and his execution were personal; four cantations were not required and not normal; execution following was not normal; it was required in this case, because his entire situation was for personal reasons and to pay the price for political changes that he had colluded in under Henry, that led to ending of the marriage and the unfair treatment of Mary’s mother. In other words Cranmer could be seen as a scapegoat; may-be some of the things he did were treason or heretical under the laws of the day, they were certainly sexed up by Foxe, who exaggerated most of what he wrote, but he was also the state’s main propaganda card in the furtherance of its own polemic that the reforms of Henry were at an end.

I’m wondering why you say the prayer book was changed in 1572 and 1922? I’m not aware of any versions from those dates; the current version is still 1662; and the only change I can find listed for 1922 is:

“The Daily Office Lectionary was changed extensively in 1871, and again in 1922. The new introduction (The Order how the rest of Holy Scripture is appointed to be read) from 1871 is considerably longer, containing nine paragraphs; the old had five. All three lectionaries are online. The 1922 Lectionary is optional, so books printed after that date may or may not include it.”

http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/Variations.htm

(Just wondering.)

There is a 1552 version, btw, described here:

http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/1552/BCP_1552.htm

There is also a 1928 version which failed to be approved by parliament.

Hello Rowan,

Correction, sorry do not know what made me think of 1572, must have been the cheese I ate late at night: sorry about that. Yes, the main changes were the two 1549 and 1552, the later had some revisions, there was a suspension during the Civil war period and under Mary, a Queen Elizabeth edition, but basically as it was, then of course the changes above after 1662. The edition of 1922 was not authorized but there was an American and Canadian version then which was completed in 1928. According to the intro to my own version, the edition in use today is from 1975. I also believe some revisions were done in 1759 but never included in the later editions. So we have what was meant to be the beautiful edition of 1662, incorporating the revision of 1552, but probably with some changes. What I love about the Common Prayer is that like the King James it seems timeless, the beauty of the language, although some words are long and hard to understand, is spiritual in itself and I think it would be a shame if there were ever too many changes or revisions. I personally like the BCP and as a member of the BCP Society have attended many services around the U.K to promote and celebrate the heritage of this wonderful work that has endured the last 300 years without too much trouble.

It is ironic that when the first edition came in 1549 that it was met by riots and risings and protests in many parts of the country. And yet it was possibly the more Catholic of the latter editions; as it was influenced by the Sarem rite and other older rites. The 1552 was meant to be more Protestant but the later 1662 seems to have revived something of the older tradition and language and that is may-be why it is so universal in its appeal. The Scots had a version in 1639 but did not want it and went to war with England; the Puritans in Scotland did not want the 1662 and the Puritans in England must have had a hard time with it as well, but it has survived even some of the modern attempts to remove it from or pews.

The new Common Worship may have much to commend it; I really have not read it, but I have looked at some parts and traditionists find it too modern and not the same, and now the fight is to hold onto the Book of Common Prayer. Personally I feel there is a place for both and would not advise or tell anyone which prayer book or Bible to read or worship from. There has to be common ground and there are many generations represented in a lot of churches with needs for different things. In our group of Churches we have prayer books services on a Thursday and every second Sunday, and Common Worship a Third Sunday and a mix on the other two Sundays. As far as I am aware all of them are well attended and in Liverpool you will not find empty church services. In fact there is a lack of clergy, not people wanting to go to Church so things have to be rotated. And with that there is a mix of prayer needs as well.

It is wonderful that there is a various KIndle and electronic versions and versions that bring the three main editions together, and a rich legacy of prayer and devotion that even none Anglicans can appreciate for beauty and spiritual worth.

Cheers.

Lyn-Marie

I think Henry VIII would have been right if he had executed Mary in 1536. She commited treason refusing to obey his laws and decision of parlaiment, regarding herself as princess, not a bastard. By doing so she posed a threat to political stability of her country. She did more than that. She wrote to Emperor Charles V in autumn of 1535 urging him to declare war against her father. If Chapuys is to be believed, during the first half of 1536 she was planning to escape abroad, to her cousin the emperor. She did not give up the idea of war. “However this may be, I must say that, notwithstanding her most ardent desire to escape from the constant anguish, tribulation, danger, as well as annoyances of all sorts by which she is beset, the Princess would still prefer a more sure and efficient remedy—one likely to arrest the growth or at least to prevent the germination of these pains and dangers [she is subjected to],—namely, that Your Majesty should diligently bestow your full attention on the means to be employed for the general and total extirpation of the evil. Not only would that be a most meritorious work in the eyes of God, it would be also the means of saving innumerable souls now on the verge of perdition, and otherwise ensuring the peace and tranquillity of Christendom. In the Princess’ sentiments in this respect I cannot help concurring, for even granting that she could be taken out of this country, which, as I have above stated, is an enterprise fraught with danger, matters would not improve much here; and, as she herself justly observes, it would thus become necessary to resort to force, when the whole affair would become more difficult than it is at present, for king Henry, who is rich and possesses great treasure, might, in desperation, engage in some enterprise against Your Majesty, or at least put himself on the defensive; whereas nowadays he is completely unprepared, and, considering himself safe, takes no precautions at all. So, at least, the Princess thinks. As to myself, I really believe that were the Princess at your Court, this King would think twice before he took a high hand and kicked against the pricks. Yet the Princess is continually soliciting me in various ways, and as earnestly as she possibly can, sending me daily messages and, so forth, to beg and entreat Your Majesty to hasten the remedy so often pointed out by her and by me, which seems to her to tarry long, and will at last come too late, so much so that, as she writes to me, she is daily preparing herself for death”. (Eustace Chapuys to the Emperor, 17 Feb.1536 // Calendar of State Papers, Spain, vol.5, part 2). If this is not treason, I don’t know the meaning of this word.

Even when Mary eventually capitulated and signed her submission, she was still a threat. The participants of the Pilgrimage of Grace demanded her restoration to the succession. She had powerful friends who opposed Henry’s religious reforms. She could have played a role of pawn in their hands. When she eventually came to power, she abandoned everything her father and brother stood for. Was she not a genuine threat to a new regime? Was it not dangerous for Protestants to keek her alive? Why then she was not executed? Very strange. If Thomas More had taken the oath demanded of him would he had been beheaded? I think, from the government point of view the best way of dealing with him would be to make him write a declaration (or several ones) where he admits his guilt in opposing Henry VIII for so long and advocating the presecution of protestants and then send him to block, condemned by his own words and actions. Why Cranmer did not suggest this idea to Cromwell and Henry? Instead he wrote to Cromwell: “I doubt not but you do right well remember, that my Lord of Rochester and Master More were contented to be sworn to the Act of the King’s succession, but not to the preamble of the same. What was the cause of their refusal thereof I am uncertain, and they would by no means express the same. Nevertheless it must needs be, either the diminution of the authority of the Bishop of Rome, or else the reprobation of the King’s first pretensed matrimony. But if they do obstinately persist in their opinions of the preamble, yet meseemeth it should not be refused, if they will be sworn to the very Act of succession: so that they will be sworn to maintain the same against all powers and potentates. For hereby shall be a great occasion to satisfy the Princess Dowager and the Lady Mary, which do think they should damn their souls, if they should abandon and relinquish their estates”. (April 17, 1534). Cranmer even bothered himself here with the state of mind of “Lady Mary”, her fear to damn her soul. What a trifling matter, he should not waste his time and paper, this lady will not reciprocate him.

Foxe wrote in his “Acts and Monements” (vol. 8, p.43): “The saying is constantly affirmed of divers, that the said archbishop, with the lord Wriothesley, kneeling and wheeping the the king’s bed-side, saved the life of queen Mary, daughter to the princess dowager, divorced as is aforesaid from the king, whose determination then was to have off her head, for certain causes of stubbornness, had not the interccession and great persuasion of this archbishop come betwixt: whereupon the king afterward, speaking of the said archbishop (whom commonly he called his priest) said that he made interccession for her, which would be his destruction, and would trouble them all. What recompense the queen rendered again for that benefit, let the world consider and judge!”

Cranmer’s secretary Ralph Morice confirmes this information. Jasper Ridley in his biography of Cranmer cites the letter, a so called “A Supplicacyon to the Quenes Maiestie” by some protestant exile: “And here I may specially make mention to your Grace of that virtuous and learned man Thomas Cranmer Archbishop of Canterbury, who hath saved your Grace’s life and put himself in jeopardy for your Grace’s cause, as it is well known by some of his enemies that were of King Edward’s Council; and I doubt not but that your Grace knoweth of it; and therefore I trust your Grace will requite him with mercy, and not suffer that wicked Bishop of Winchester to have his wicked will and purpose of him”. Let the world consider and judge.

Do you not think there would be some serious repercussions if Henry did remove his daughter’s head too?

She may have posed a threat alive, but dead…and not by natural causes but on the command of her father, a very risky move to my mind…

Also, Mary was the de facto heiress from the death of Henry Fitzroy in summer of 1536 to the birth of Edward in 1537 … executing her during that time means that no Tudor would inherit if something happened to Henry (Elizabeth being too young and having no powerful backers). Executing her would give all Europe a brilliant excuse for invading.

Seriously, I think it proved to be a huge mistake to burn Cranmer for heresy instead of hanging, drawing and quartering him for treason. His recantation, by law, should have blocked his burning, but recantation did not end the punishment for treason (as the Duke of Northumberland’s fate illustrated) … so if Mary went with treason, her revenge would have been legal.

Henry would have taken a terrible risk executing his own daughter. It is not treason to stand up for your parents and faith. Yes, the Treasons Act and Acts of Supremacy and Succession changed everything investing the succession in the children of Henry and Anne, the Supremacy made Henry Head of the Church in England instead of the Pope and others had died for not taking the oath. In the eyes of the laws at that time, it could be said Mary was a traitor, as it was said that Thomas More and Fisher were and the monks of the Charter House in London and so many others, but where they? Of course not! It is not treason to hold the Pope as head instead of Henry or every Catholic in England today would have to be called a traitor. The Queen now may be supreme govenor but she does not use the title in the same way Henry did . Thankfully these ridiculous laws have gone.

Mary was also the only heir other than Elizabeth unless Henry and Anne had a son and Henry was not stupid; he was not going to get rid of a daughter that he loved, no matter how disobedient she appeared; or that he may need to succeed him. He was also not going to risk war with the Emperor. Mary did not want the Emperor to invade but to intervene and that does not mean invassion, but pressure on her father. We put pressure on countries today with sanctions, we do not invade everyone we do not agree with; not at the moment anyway. She also hoped for rescue and that Henry would change his mind. in fact she blamed Anne for her problems, but pressure increased on her to comply when Anne died and she was forced to submit to her father and accept that her parents were not lawfully married. She had to make a promise that she must have felt ill at the thought of doing; that she accepted Henry as head of the church and her parents had lived in sin. She had to also make a declaration apart, where she secretly forswore this and sought a pardon from the Pope.

Mary was a teenage girl, separated from her mother, thrust into the service of the new Princess that had taken her lawful place, declared a bastard, banished from her father, the court and her friends, and denied all of her lawful rights. Her life was in constant danger and she was not even allowed to see her dying mother. She was bullied and tormented and was in constant danger and fear. I would have tried to escape if i was her as well. I do not understand what you mean by she did not give up war; she did not want war; she wanted her situation to change.

As to whether or not she took her revenge on Cranmer who she must have also blamed for causing her problems, and for seperating her parents, that is open to debate. Cranmer could have been executed for treason rather than heresy simply as he had been involved in the plots around Lady Jane Grey. Mary was not seeking revenge when she tried Cranmer, she was seeking justice. Cranmer was a man of great bravery and to be admired for his final courage, but he did give Mary the excuse to condemn him when he supported the plots against her life and her throne.

Justice? Humiliate sick old man for more than two years, the man who pleaded for her with her father, who tried to understand her situation – that’s what you call justice. Mary jurged the prince of another country to make war on her motherland. (“as she herself justly observes, it would thus become necessary to resort to force”) Is it not treason? She was separated from her mother. But Cranmer, was he not separated from his children? Did he not suffer when he saw the slow death of his old friends, when Mary’s agents forced him to repudiate everything what was dear to him, sign his so called recantations? You said that Mary was also forced to admit her bastardy. But after that she was restored to favour. She was not sent to block. Cranmer was. Do you see the difference? Cranmer separated her parents? I always thought it was Anne Boleyn and Henry’s desire to have a son. Do you really think that if it was not for Cranmer, Mary’s parents would have lived happily together and had no problems? Mary and her church committed a crime, that’s plain truth.

Mary did not commit any crime; she had the same idea about the prosecution of heretical ideas as every other monarch at the time. Protestants and Catholics burnt what they believed to be heretics; Protestants burnt Anabaptists and others, 16 of them in the short reign of Edward VI, and others were also burnt under Elizabeth and James I, both Protestant monarchs I believe. Puritans were also persecuted under both of the later, some put in prison or killed as well as exile. Mary does not stand out for her prosecution of heretics, she stands out for the excessive number that she prosecuted. I will leave it to historians to debate the reasons behind that, as it is not relevant here; but even in Europe it stood out because it was over a short few years. The lines also became blurred between treason and heresy at this time, with some, like Cranmer facing both charges.

Mary was the annointed Queen; the laws that she passed were sanctioned by Parliament and her council and many were in agreement with them. Cranmer was condemned by the law and died under the law. Just because you do not like it does not mean that it was a crime. You seem to be just wanting to rant and not to reason, and you want him to have an even more painful death for treason, and others killed as well. What makes Henry VIII right to make laws that condemned someone for their religious beliefs by taking the rightful title accorded only to the Holy Father in Mary’s eyes right, and Mary wrong to do the same thing? Your reasoning is not sound. Henry’s laws that made it treason to say that Mary was not legitimate or that he was the head of the church in her eyes were unlawful, just as they would be seen today. In the same vein, by your argument the laws that condemned Cranmer and others were also unjust, and some of those laws were, but you cannot say Mary should have been killed and Cranmer not when by the standards of the time they both should have faced treason charges. Oh but then, this is Mary, so in your book, she is wrong; but of course Henry is not?

How could Mary be asked to say her own parents whom she loved where not lawfully married? She was 18 years old and since 11 had been the official heir to the throne as Princess of Wales, since she was a baby she had been the centre of their world and loved both of them, she was raised to rule. Now she was being asked to declare everything she had known as wrong. She was being asked to accept a woman, whom to be fair she hardly knew as her step mother, a woman that in her eyes she believed had been the cause of the divorce and her mother’s sorrows? It was not going to be an easy thing for any young woman to do; let alone a Princess. Anne may have made efforts at first to try and win Mary around but things did not go well and neither woman was going to give in during the next few years. Mary was faced with death before she agreed to accept her father’s will and she felt she was left with no choice. She was in constant fear of being poisoned and she saw her mother live her last few years in exile and pain and was not allowed to be at her side even when she died. I think Mary went through enough and did not deserve to be condemned as she was. May-be all of this shaped her hardening towards Cranmer and others; we cannot really know for certain, for there is no evidence that she acted out of cruelty or revenge, but in the end the law condemned Cranmer and others and not Mary. It was certainly not a crime; not in the way you see it anyway.

*keep her alive*

For what Mary had to revenge Cranmer? For him trying to save her life? What treason did he make? Obeying the will of his king Edward? Staying loyal to queen Jane? All political establishment agreed to pass crown to Jane Grey, all members of the council served her during her short reign. Why not execute all of them? Or hanging, drawing and quartering is the most usual fate for senior clergyman of the country, respectable old man?

Of course, I think Henry would never have executed Mary. For political as well as moral reasons. Although world history knows examples when monarchs put to death their adult offsprings if they became opponents of their policy. But I tried to use the same logic as those who justify Cranmer’s execution. Mary as a traitor, religious dissident and the person who violated the laws of her father and brother could be brought to the scaffold or put under arest very legally. If we accept the fate of Cranmer and Mary’s right to kill him, we should also approve these actions against her. At least Cranmer did not call on foreign powers to invade his country. As for me I can’t find a word in her defence.

Of course there is no defence for this brutal act, or any of the many other injustices meted out through Mary’s reign, and your logic is probably correct, but I personally do not think Mary was acting in a logical mind.

She was a damaged woman. Abandoned, ill treated, humiliated and scared witless for most of her life, she witnessed these same ‘courtesies’ applied to her mother. Not an excuse, but a valid reason why perhaps she behaved as she did, and spiralled deeper into this ‘mind-set’ of despair, intolerance and revengefulness which proved fatal to many innocent people.

I have not been Mary’s greatest fan and have judged her most harshly in the past, but put in her shoes would I, or any of us have behaved any differently given the era and her mental state…I’m glad I never had to find out.

Maybe you are right and Mary was a damaged woman with psychological problems. Maybe she was just religious fanatic and her militant catholicism is accountable for those crimes against humanity which happened during her reign. What’s clear for me is that such people should not be allowed to have power.

I quite agree with you, but whether she was fit to rule wasn’t up for debate, she was heir through birth and law, named by her father after Edward. She had absolute power, and the divine right of Kings, although this was beginning to be questioned around Mary’s reign it took Oliver Cromwell to wrestle this from the crown…that’s if I’ve got my history right!

To be quite honest I don’t think Mary was any worse than Monarchs that preceded or followed her, there were many atrocities committed by most of them be it on religious or other grounds…Look how many were killed in the crusades by Richard 1st, that went into the millions.

Maybe she is judged more harshly because she was a women, who knows!

Yet another senseless murder in Thomas cranmer,They ,starting with henry viii were nothing but a bunch of power hungry corrupt people who murdered anyone who did not agree with their very flawed sense of ideals,They had a ridiculously lavish ,really over the top,lifestyle ,not one of them im sure thought anything about the poor and hungry in their country,while “they”spent huge amounts of money on themselves and their cronies ,surely no one can think or associate respect with these psychos.

Things not changed that much then….sounds like most of the worlds top politicians/leaders to me… 🙂

Of course, Mary I was not the only ruler in history who committed atrocities. Is she judged more harshly because of her sex? Personally I think, women must be kinder than men. They give birth, give life. And when they want to take away this life, to hurt and torment other people… to me it seems unnatural. But I don’t support male dictators also, especially those of modern times.

I have read and saw a documentary about women that commit violent crimes ages ago, can’t think what they were called now, but this was discussed…’the gentler sex’, she who gives life, nurtures, protects etc., and how she is held as more abhorrent than a man who commits the same crime.

In the past, and up to not long ago, and there is documented evidence,, that shows a sentence a woman received for a violent act, which are usually seen as men’s crimes, were harsher…and the only logic that can be put behind that is our preconceived ideas on what a woman is, yet there has been female warriors throughout history, but we choose to ignore this…

The human race can have a very contradictory views on what is right and wrong, and I know I’m diversifying here a little but look at what women did in WW2, they did hard physical, manual labour ‘men’s work’, raised the family on rationed food etc. When the men came home, attitudes reverted back to type, Men’s work and women’s work, and this prejudice carried on to not to long ago. In the 1990’s I learnt to drive my husbands articulate, 38 ton lorry, then his motor bike, much to the disgust of many males, particularly those of my age and younger…it is a mind set that is still ‘bred’ into us even in these modern times.

It’s one area I feel that’s not yet reached equality in the acceptance that women can actually behave as men,.and should not be judged more harshly for it, even when they step into the realms of brutality. And I have been guilty of this myself …but my views have changed over time, it’s not what sex you are, it’s what’s going on inside the mind thats the issue. Sorry for rattling on 🙂

I fully agree with you.