Thank you to author Amanda Harvey Purse for sharing this article with us here today. Over to Amanda…

‘Sir Christopher Hales’ is perhaps one of those names that may feel as if they briefly pop up as a part of a historical Tudor fact within a Tudor event and then goes away again. However, the person behind that name in reality rarely does. Sir Christopher was the Attorney General in many of the famous Tudor trials that were formed mainly because of King Henry VIII’s anger and/or mistrust.

But what of the man that sat in the courtrooms, facing these famous Tudor people of King Henry VIII’s court that were at one point high ranked?

Christopher Hales had his family roots set firmly in Norfolk, just like the Boleyns, with Roger de Hales, sometimes called Ralph de Hales, gaining property in Norfolk in the reign of King Henry II. However, before the end of King Edward III’s reign, the Hales family had moved down to Kent in a similar fashion to what the Boleyns would do later. The Boleyns would, in fact, later own many properties around the Hever area, whereas the Hales would situate themselves in the nearby town of Tenterden in Kent (Hales, Sir Christopher Master of Rolls by J. M. Rigg. Dictionary of National Biography 1890).

With this known, can we now wonder if, through a distant connected way, the Hales and Boleyn had known each other for many years? With this questioned, would this have made a future event that will be mentioned later, even more poignant to Christopher?

Christopher was born to Thomas and Alicia Hales by the late 1400s. He went straight into a legal career, learning his trade at Gray’s Inn. By 1516 he was an ancient and became a member of the learned counsel in the Cinque Port town of Rye in East Sussex, one year later. In 1520, after John Hales, his cousin, was Baron of the Exchequer, Christopher became solicitor general before gaining his cousin’s seat in the House of Commons for Canterbury in 1523 (Rye Chamberlains accounts. 3, f.52v; Cinque Ports White and Black Books. Kent Archives).

Christopher became the attorney general to the Duke of Buckingham as well as being the appointed resident counsellor for Princess Mary, the future Queen Mary I. Although he was appointed ‘resident’, there are doubts whether he actually travelled to Ludlow Castle or was her council from afar. As attorney general, he appeared for the king in many famous trials such as those of Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher, who refused the oath of Supremacy, to name but a few.

Christopher became closely linked to Thomas Cromwell, a temporary supporter of Anne Boleyn, when he married Elizabeth Caunton, the sister of Cromwell’s servant, Nicholas Caunton. There was also correspondence later between these two men about the Lincolnshire Rebels of 1536 (Letters and Papers Henry VIII – xiii SP1/29 f.179; Elton, Policy and Police 295, 311, 404).

Christopher would take over Cromwell’s previous role as Master of Rolls on 10th July 1536, before gaining a knighthood within the same year, he would keep this role for the last remaining years of his life. As well as having a high ranked friend in Thomas Cromwell, Christopher would also work later within his life, with Thomas Cranmer, Lord Chancellor Rich, and other well-known men within Henry VIII’s court on the remodelling of the foundation of Canterbury Cathedral in 1540. This included removing the monks that were living there, for a clergy that was not bound by religious rule. All in all, Christopher did profit largely from the Dissolution of the Monasteries, gaining many lands within Kent because of it (Hales, Sir Christopher Master of Rolls by J. M. Rigg 1890).

It would be through Christopher’s daughter, Elizabeth, that his family would have links to the famous Elizabethan courtier, Sir Frances Drake of the Golden Hind fame. This would be because his daughter Elizabeth would go on to marry Sir George Sydenham and have a child, also called Elizabeth. This Elizabeth would then become the second wife to Sir Francis Drake. Christopher would also have two other daughters, Mary and Margaret, and one son, who they named John Hales, sadly this John Hales was to pass away at the young age of fourteen in 1546.

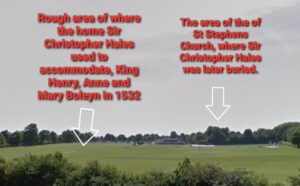

Being closely linked to Kent, having been a steward of Canterbury and Rochester, he had many properties within this county, one of which, at Hackington near Canterbury he had allowed to be used as somewhere to rest for King Henry, Anne, and Mary Boleyn as they travelled down from London to Dover, before crossing the English Channel to France in the October of 1532. The Royal party had already visited Canterbury Cathedral at this point and if this event was to help Anne Boleyn to become popular in the eyes of the public, this point at Canterbury, made the trip a disaster. As King Henry and Anne entered the cathedral, a nun called Elizabeth Barton, who had become famous of her prophecies and who King Henry himself had visited twice before, shouted that if he was to marry Anne, the king would die within months, this caused a scandal and enhanced many of the public’s suspicions of Anne. Elizabeth was executed over a year later; the lateness of the execution was due to the popularity of her claims.

The place Christopher could have used to house King Henry, Anne Boleyn, and her sister, would dip in and out of his family’s hands after his death in 1541, with the estate passing into the hands of Christopher’s wife as directed in his will. However, she was to later marry John Culpeper, and the Culpepers went on to sell it. Eventually, the estate fell back to a Sir Edward Hales in 1675, and Edward knocked the whole place down to build a Palladian styled building, before the property was eventually demolished. The area where Christopher’s home was once located, is now a part of the local school’s playing field with St Stephen’s Church, Hackington in the background (Letters and Papers Henry VIII, xvii).

This church would have been known to Christopher, as it once held a statue of him inside. However, there is a suggestion that Christopher had convinced the king to take it from the archdeacon and probably gained a temporary grant of it afterwards for Christopher to have it for himself (The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 9. W Bristow, Canterbury 1800).

On 15th May 1536, the strangest event occurred within Christopher’s career. He walked into the King’s Hall within the Tower of London (no longer there) and took up his role as Attorney General for the King of England at a trial like no other. Christopher had to preside over a trial of treason. The criminal? None other than the Queen of England, King Henry’s wife, Anne Boleyn.

One wonders how Christopher truly felt over this moment?

Of course, we will never know for sure, Christopher would certainly not have been allowed to show any thought of his own in this matter and in all probability, he had possibly been told what would happen.

However, now knowing his background. Knowing that he may have had a connection to the Boleyn family, knowing that he had once given one of his homes for Anne and her sister to stay in. Knowing his closeness to Thomas Cromwell, who at one time was a supporter of Anne but now was probably the architect, from orders higher than himself, of this whole event. Knowing all that, one wonders how Sir Christopher Hales felt when he stared into the eyes of Anne Boleyn on this day in May 1536.

In this vast room, Christopher was with the Mayor of London, Sir John Aleyn, the French ambassador, diplomats, members of the public and the panel of judges that were considered to have been Anne Boleyn’s ‘peers’, however it’s debatable whether Anne viewed them as such.

The panel included the Earl of Sussex and Charles Brandon, who were King Henry’s best friends and no supporters of Anne; the king’s friends, Lord Grey of Powys, Lord Monteagle, Lord Sandys and Lord Windsor; and the Marquis of Exeter and Lord Montague, both of whom were supporters of Lady Mary, daughter of King Henry and Katherine Aragon, and so by definition, no supporters of Anne.

There was also the Earl of Northumberland, Henry Percy, the man Anne had wanted to marry before the king took an interest, but he was too ill to sit for the full trial. There was Ralph Neville, an already proven loyal servant to the king; the Earl of Worcester, whose wife had given evidence against Anne; the Earl of Rutland and the Earl of Huntingdon, who were not only loyal to the king but were related to him; Lord Dacre, who had previously been accused of treason himself and only just survived, so would have been on good behaviour for the king; Lord Cobham, who quite possibly had a wife who gave evidence against Anne, and Lord Clinton, who was the step-father of King Henry’s illegitimate, and, at that time, only son, so he had an invested interest in getting Anne out of the way.

Finally, two people who really sit uncomfortably to be considered as Anne’s ‘peers’ to be able to judge her, and they, themselves probably did sit uncomfortably within the courtroom at the time too. These were Lord Morley, father-in-law to Anne’s brother, George Boleyn (also on trial that same day), and Lord Wentworth, who, believe it or not, was actually related to Jane Seymour, whom King Henry would marry within days of Anne Boleyn’s death! One could say… this trial was a one-sided affair (Letters and Papers of Henry VIII).

Nevertheless, the room was packed. Everyone was watching every move, every action that was made, and of course, the king had ears and eyes everywhere, even if he wasn’t in the actual room. What pressure Christopher must have felt at this point?

There was one person we have not mentioned who was within this room too, and it would be this person who read Anne’s sentence out – her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk.

He stated out loud ‘Because thou hast offended against our sovereign the King’s Grace in committing treason against his person, and here attained of the same, the law of the realm is this, that thou hast deserved death, and thy judgment is tis: that thou shalt be burned here within the Tower of London on the Green, else to have thy head smitten off, as the King’s pleasure shall be further known of the same’ (Spelman Reports i.71 as Quoted in The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn by Eric Ives. Wiley-Blackwell 2005).

It has been suggested, through Sir Henry Norris’s manservant, that as the Duke of Norfolk read out this sentence to his niece, tears had coursed down his face.

Was he the only one to show emotion?

Would Christopher have shown emotion, whether it be through physical tears or a lump in his throat? Sadly, we will probably never know. What we do know is, that at this point of hearing Anne’s sentence, the Earl of Northumberland, Anne’s past sweetheart, collapsed and had to be taken out of court, showing the deep emotion many people could have possibly had at the time (The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn by Eric Ives. Wiley-Blackwell 2005).

Anne herself was described later as being calm. Ambassador Chapuys wrote, ‘The Concubine was condemned first, and having heard the sentence, which was to be burnt or beheaded at the King’s pleasure, she preserved her composure…’ (Letters and Papers Henry VIII).

Would this have helped others in the room to find their feet, to focus on the task at hand? Would this have helped Christopher in his role? Or make the situation more special, more poignant for him?

After being found guilty, Anne Boleyn was escorted out of the room and taken the short distance back to the Queen’s Royal Apartments (no longer there) within the Tower of London, where she had been held as a prisoner. Later that same day, Christopher would be in the King’s Hall again to hear the sentence of Anne’s brother, George Boleyn.

How did Christopher feel over this most strange of events? Did he let the emotion of the day drain him? Did he care? Or did he see this as another moment within his career, that pushed his importance within the Tudor court? Sadly, we will probably never know.

Christopher was to pass away in the June of 1541, being buried within the church that was close to the property that Christopher had provided for the king, Anne Boleyn and her sister to use to rest in 1532, at Stephen’s Church, Hackington, near Canterbury.

Written by author and historian Amanda Harvey Purse.

Amanda, a member of the Royal Historical Society, has worked with many museums and television programmes on a range of subjects from the Tudors to the Victorians. She has written many historical books such as Martha, the life and times of Martha Tabram, a suggested victim of Jack the Ripper. Jack and Old Jewry: The City of London Policemen who Hunted the Ripper and the award-winning, Inspector Reid: The Real Ripper Street.

This article is a part of her research for her next book, titled The Boleyns: From the Tudors to the Windsors, published by Amberley Publishing and due out in 2021.