As I wrote in “The Early Life of Anne Boleyn Part Two – The Court of Margaret of Austria”, Anne Boleyn was sent to the court of Margaret of Austria in the Low Countries in 1513 to finish her education. However, she only remained at Mechelen for around 15 months because, in August 1514, Anne Boleyn’s name was on the list of attendants chosen to accompany Mary Tudor to France for her marriage to King Louis XII.

Anne Boleyn Summoned to France

On the 14th August 1514, Thomas Boleyn1 wrote to his great friend, Margaret of Austria, asking her to release Anne and send her back to England with a chaperone sent by him. It seems that Anne had been chosen due to her fluency in French and, as Thomas Boleyn wrote to Margaret, it was a request that “I could not, nor did I know how to refuse.”2 Although it is clear from Thomas Boleyn’s letter that Anne had been chosen to attend the new Queen of France, the records are not exactly clear as to which Boleyn girl travelled to France with Mary and where Anne joined her new mistress. Eric Ives writes of how the list of ladies paid for the period October to December 1514 shows the name “Marie Boulonne”, but not Anne, so it may be that Mary Boleyn attended Mary Tudor on her crossing to France, for the wedding which took place on the 9th October 1514 at Abbeville, and that Anne caught up with the royal party in Paris when Mary was crowned queen on the 9th November. Ives hypothesises that Margaret of Austria may not have got Thomas Boleyn’s letter in time to send Anne home to England, because she was visiting the islands of Zeeland at the time, so Anne travelled directly to France.

What we don’t know for sure is whether the “Madamoyselle Boleyne” mentioned by King Louis XII in his “Names of the gentlemen and ladies retained by the King (Louis XII.)3 to do service to the Queen” refers to Mary or Anne, but what we do know is that Anne Boleyn did, at some time, arrive in France to serve the new queen.

On the 1st January 1515, less than 3 months after his marriage to his 18 year old bride, the 52 year old Louis XII died. It was said that he had been worn out by sexual relations with his younger wife. Louis had no son and Salic Law prevented his daughter, Claude, from becoming queen so when it was clear that Mary Tudor was not pregnant, Claude’s husband, who was also Louis’s first cousin’s son, Francis, inherited the throne and became Francis I of France. Mary Tudor had never wanted to marry the ageing Louis XII as she had already set her heart on Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk, so when her brother, Henry VIII, sent Brandon to bring her back home to England, she followed her heart and married Brandon in secret on the 3rd March 1515 in France. Although this was an act of treason and Henry VIII was furious, he eventually forgave the couple and they were officially married on the 13th May 1515 at Greenwich Palace, having been fined for their disobedience.

Even though Anne Boleyn was one of Mary Tudor’s attendants, she did not travel back to England with Mary in 1515, but, instead stayed on in France and served the new queen consort, Queen Claude. How and why, we just don’t know, but it’s possible, as Ives ponders, that the 15 year old Claude had taken a liking to Anne when she had served her stepmother and so offered her a place at her court when Mary returned to England in April 1515. Claude and Anne were of a similar age and Anne was fluent in French, and it is possible that Anne had acted as an interpreter between Claude and Mary Tudor. Anne went on to serve Queen Claude for seven years and, as Eric Ives points out, it is a period of Anne’s life which we know relatively little about.

The French Legends and Traditions Regarding Anne Boleyn

French tradition links Anne Boleyn with Briare, a town on the river Loire, and also the village of Briis-sous-Forges where there is even a tower called the Tour d’Anne Boleyn. According to one French website4, this tower is the only remaining part of a medieval castle which was once stayed in by Anne, before her marriage to Henry VIII, because her parents were friends of Du Moulin, the owner of the castle. This story is backed up by the work of French historian, Julien Brodeau (1654)5, who wrote that Anne Boleyn was educated in the home of nobleman Philippe de Moulin de Brie, a relation of her parents.

Nicholas Sander, writing in the reign of Elizabeth I, wrote that Anne Boleyn was sent to France at the age of 15 after she had “sinned first with her father’s butler, and then with his chaplain” and was placed “under the care of a certain nobleman not far from Brie”. Sander also writes that “soon afterwards she appeared at the French court where she was called the English Mare, because of her shameless behaviour; and then the royal mule, when she became acquainted with the king of France”6, which makes me wonder if he was confusing Anne with her sister, Mary Boleyn, who was the mistress of King Francis I and who was, apparently, referred to by the King as an “English Mare” and “una grandissima ribalda, infame sopra tutte” (a great and infamous wh*re).

Alison Weir, in one of her recent talks on Mary Boleyn, quoted historian Sarah Tytler (1896) as saying that Anne Boleyn went to a convent school at Brie to finish her education. However, Weir wonders if historians have confused the two Boleyn girls and hypothesises that the Boleyns, upset at Mary’s bad behaviour at the French court, could have entered her into a French convent for educational purposes.

Eric Ives writes that the link between Anne Boleyn and Briare could have some foundation because “the town was well placed in relation to the movements of the court of Queen Claude, where Anne’s duties kept her.”7 Claude was constantly pregnant, giving birth to seven children between 1515 and 1523, and she tended to spend her pregnancies in the Upper Loire area, at Amboise and her palace in Blois, and Anne would obviously have accompanied her there.

The French Court

Eric Ives writes of how “waiting on the queen of France could not have been markedly different from waiting on the regent of the Low Countries, and it is clear that Anne continued to soak in the sophisticated atmosphere around her.”8 He quotes Lancelot de Carles, “she knew perfectly how to sing and dance… to play the lute and other instruments” and Nicholas Sander, who, in his book “Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism” said of Anne “She was handsome to look at, with a pretty mouth, amusing in her ways, playing well on the lute, and was a good dancer. She was the model and mirror of those who were at court, for she was always well dressed, and every day made some change in the fashion of her garments.”9 It is clear that Anne had learned music, dance and style during her time in France.

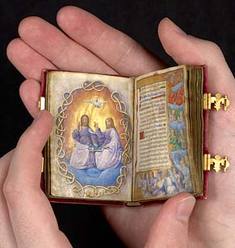

I mentioned in Part Two that Anne Boleyn’s love of illuminated manuscripts had begun at the court of Margaret of Austria, who had a vast collection of them, but if it began in the Low Countries it blossomed in France because Queen Claude also loved illumination, as is clear when we examine her Prayer Book and Book of Hours from 1517. Roger Wieck, curator of the Morgan Museum, has done a wonderful video about Queen Claude’s prayer book, where you can see the exquisite illuminated pages – see http://www.themorgan.org/collections/multimedia/claude/default.asp.

Anne Boleyn went on to have her own illuminated manuscripts and books and they were made in the Renaissance style, which had been popular in France and used by Claude, rather than the style she had seen in the Low Countries. Like Margaret of Austria, Claude was also an art lover (she was a patron of the miniature) and Eric Ives comments that as Leonardo da Vinci settled at Cloux, near Amboise, in 1516, it is likely that Anne met him. In the Low Countries and in France, Anne was surrounded by art and culture, she couldn’t help but be influenced by this amazing experience.

Some people seeking to blacken Anne Boleyn’s name say that Anne must have been influenced by the loose morals and sexuality of the French court, but we have to remember that Anne Boleyn was serving Queen Claude, a woman known for her piety and a woman who was often away from court due to her annual pregnancies. Anne was serving in a morally strict household, not one of scandal. As well as her day-to-day duties, as a maid-of-honour, Eric Ives writes that Anne may well have accompanied Claude and her mother-in-law, Louise of Savoy, on their journey to Lyons and Marseilles to welcome back Francis I in October 1515 after his victory at the Battle of Marignano in Italy. While the women were in the area, they went on a pilgrimage to Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume to see the alleged tomb of Mary Magdalene. The story behind this tomb is that on the 12th December 1279 a sarcophagus proclaimed to be that of Mary Magdalene was found in the crypt. It was said that Mary Magdalene had fled the Holy Land on a boat with neither rudder nor sail, landed at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer and then travelled to Marseilles where she converted the locals. According to legend, she retired to a cave in the mountains of Sainte-Baume later in her life and was buried in Saint-Maximin. The basilica of Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume was built in the late 13th century and early 14th century and the crypt was consecrated in 1316.

Anne Boleyn would also have probably taken part in the coronation of Queen Claude at St Denis in May 1516 and her triumphant entry into Paris, and also her entry into Cognac in 1520. Queen Claude was also present at the banquet given in honour of the visit of the English diplomats sent to negotiate a marriage between the Dauphin and Henry VIII’s daughter, Mary, at the Bastille on the 22nd December 1518, and also at the Field of Cloth of Gold in June 1520, just outside Calais. Claude was accompanied by her ladies at both events and it is likely that Anne would have been useful as an interpreter. Eric Ives writes that Queen Claude and her ladies made quite an impression at the joust at the Field of Cloth of Gold:-

“She [Claude] wore cloth of silver over an underskirt of cloth of gold and rode in her coronation litter of cloth of silver decorated with friars’ knots in gold, a device which she had taken from her mother. Her ladies rode in three carriages similarly draped in silver and, no doubt, were dressed to match the queen.”10

Ives also writes of how Queen Claude played the hostess when the two kings, attended by the gentlemen and ladies of the French and English courts dressed in masque costume, changed places. Anne must have been there and she must have seen her future husband, Henry VIII; however, it was Mary Boleyn, not Anne, who was catching the eye of the King at this time. Anne must have also seen her sister, brother and father at this event – a Boleyn family reunion. I wonder if they were impressed by Anne, if they even recognised the accomplished woman who stood before them. She was no longer a Kent country girl, albeit a courtier’s daughter, she was now an educated and cultivated Renaissance woman.

But it wasn’t just the Renaissance culture of France which had influenced Anne Boleyn and made her the woman she was when she returned to England in 1522, it was also the women she met and spent time with, women such as Louise of Savoy, Marguerite of Angoulême, Queen Claude, Renée of France and Diane de Poitiers. I will be writing about them in Part Four.

Notes and Sources

- The Youth of Anne Boleyn, article by Hugh Paget, p166

- The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, Eric Ives, p27

- LP i.3357

- http://fr.topic-topos.com/tour-danne-boleyn-briis-sous-forges

- The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn, Retha Warnicke, p 246

- Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism, Nicholas Sander (1585), p25-26

- Ives, p29

- Ibid.

- Sander, p25

- Ives, p32