Thank you to author Amanda Harvey Purse for sharing this article with us today, an article which is based on research she did for her book on the Boleyns.

Over to Amanda..

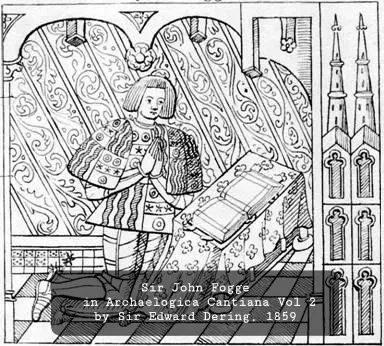

On 9th October 2019, The Anne Boleyn Files kindly published my article of research on Sir John Fogge and his connection with the Boleyn family, research from my forthcoming book, The Boleyns: From the Tudors to the Windsors – see the article here. However, this was not the first time I had heard of the name Sir John Fogge. This shows that events within history, through connections, can work in circles, often bringing a researcher back to where they had originally started from. For this particular article, I would like to discuss the full circle I have been on with the family of Sir John Fogge and the many interesting twists and turns that can connect the Boleyn extended family to the story of King Richard III, and even the story of the ‘Princes in the Tower’.

It was in 1991 that I first came across the name Sir John Fogge. This was when a local writing competition was launched, asking for people to write a compelling story. Unbeknown to me, this would be my first chance to write as a researcher and, to some extent, a historian. I can safely state that I caught the writing bug at this moment thirty years ago.

I chose to write on the story of Richard Plantagenet, known to some as Richard of Eastwell. This was the story suggested to have been mainly brought about in Francis Peck’s Desiderata Curiosa, printed between 1732 and 1735. This book came in two volumes: the first was mainly a biography of Queen Elizabeth I’s Lord High Treasurer, Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley, but the second, however, contained other interesting articles, and one was about Richard Plantagenet.

This is not the story of King Richard III, the last Plantagenet king, as you may expect from the naming of this person. I certainly was shocked to find that out at the time, but rather the story of his illegitimate son.

Richard Plantagenet of Eastwell

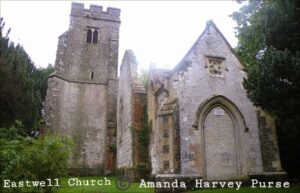

The story has its basis in a letter allegedly written by a clergyman from Wye, near Ashford, in 1733. In this story, Richard Plantagenet never knew his parents and was trained to be a bricklayer by a Kent family. In 1485, this boy was taken to the Battle of Bosworth, where he met King Richard III and was told that he was the king’s son. If King Richard won the battle, the boy would be classed his heir; however, if King Richard lost or died in battle, the son was to carry on the life he had started in Kent without uncovering his true identity. As we know, King Richard lost and died at the Battle of Bosworth and the ‘son’ is said to have travelled back to Ashford in Kent, where he later died, being buried in Eastwell Church.1

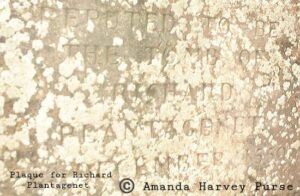

There is now, as was the case in 1991, no real evidence for this story. However, because of one single document, I was interested in finding out more at the time. This document was a church burial record for Monday 22nd December 1550. It stated that a man named ‘Rychard Plantagenet’ was buried at Eastwell Church.2 Visiting the ruins of Eastwell Church, I was also able to discover a stone tomb in its grounds. Overgrown with plant life, this tomb was not in great condition; weather and time were factors. However, there was a stone plaque placed at one end of this tomb – again not in the best condition (but has since been cleaned) – perhaps highlighting that it had been placed there a while ago, but the words could still be read. Those were: ‘Reputed to be the tomb of Richard Plantagenet, 22nd December 1550’

This could be seen as convincing proof that the story of King Richard III’s son was true. In fact, proof that this story was still believed became clear in 2013, when probably due to the popularity in the finding of King Richard’s body in a car park in Leicester through the use of DNA techniques, the BBC reported that Councillor Winston Michael, who, they stated represented Eastwell at the time, wanted the same DNA techniques used to identify King Richard to identify his purported son.3

When I looked into the history of this tomb, I found that the slab on top was once said to have depicted a husband and wife, with children, wearing clothes that were the fashion in the 1480s. However, the Richard of this story is not meant to have had a wife or children, and the clothing seemed to suggest that this tomb was for a family that had died before Richard’s death. This could also suggest that the plaque with Richard’s name on it was added much later and that Richard’s burial place has been lost.

What has this got to do with Sir John Fogge?

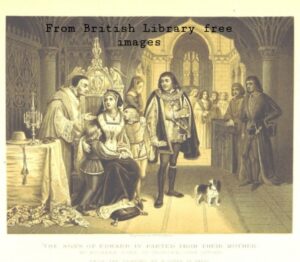

There is another theory about Richard Plantagenet. Could it possibly be that in 1483 when King Richard had left London for his Progress around the country, that an attempt was made to abduct King Edward IV’s sons, the later mentioned ‘Princes in the Tower’, during ‘Buckingham’s Rebellion’? What if this abduction was successful? Would this explain why, when King Richard was being accused of doing away with the boys, that he did not show the boys to the world to prove his innocence? Was it that he couldn’t show them because they had already been taken from his care, which wouldn’t have looked good for him?

It has been suggested that the older of the two boys, Edward, was a weak child. So, this brings a suggestion that Edward may have died, due to his ill health, while in the Tower of London, but what of the other boy, the other brother, named Richard? Did he escape, and, if so, where did he go?

It is rather interesting, although it doesn’t prove anything, that when in King Henry VII’s reign there were pretenders to his throne, the ones suggesting they were Edward seem to have been dismissed rather quickly. Still, the one suggesting he was Richard seems to have been taken at the time with more interest.

This theory goes that Richard, Duke of Shrewsbury, the boy in the tower, was sent to live with one of his abductors to live out his life quietly and secretly. What if one of the abductors was Sir John Fogge?

He was a man known to have sided with the ‘Earl of Richmond’, the future King Henry VII, rather than King Richard. More importantly, he had been previously loyal to King Edward IV and had been given the role of Chamberlain to the Prince of Wales, Edward, the older boy in the tower. So, it is possible that he would have known King Edward IV’s boys very well indeed. Could this suggest a man willing to rescue King Edward IV’s boys while King Richard was away?

In ‘Buckingham’s Rebellion’, when the Duke of Buckingham had tried to gain support to overthrow King Richard, most of Buckingham’s supporters came from Kent. Sir John came from Ashford in Kent, and he owned many lands within that county.

We also know that Sir John had married for the second time to Alice Haute in 1458. This marriage is important for two reasons; firstly, the couple had three daughters, Anne, Elizabeth and Margaret Fogge. Margaret Fogge later married Sir Humphrey Stafford. They had met through her father, Sir John, as Humphrey Strafford was Sir John’s ward. Margaret and Sir Humphrey would have six children in total, three sons and three daughters. The second son of this couple was William Stafford. As the second son, William was not seen as a man of high status, so became a soldier for King Henry VIII and later became one of the king’s bodyguards.4

The Boleyn Connection

In 1532, William was one of the soldiers who travelled to France with the king. The reason for this event was for the king to show off his new wife-to-be, Anne Boleyn, and hopefully get the King of France’s support for King Henry’s annulment of his first marriage.

Anne’s sister, Mary Boleyn, was also on this trip. This could be the moment where William Stafford and Mary Boleyn met and fell in love. Being the daughter of Thomas Boleyn, the niece of Thomas Howard, two important men within the English Court and the sister to the next Queen of England, Mary must have seemed to have had excellent marriage prospects for William.

Although William had his own connections to the royal family – he was, after all, the second cousin of King Henry VIII’s grandmother – the connection wasn’t close, so William was considered a commoner, certainly in the eyes of the Boleyn family anyway.

The Woodville (or Wydeville) Connection

The second reason why the marriage between Sir John Fogge and Alice Haute could be deemed as important is that it gave Sir John family connections to the Woodville (also known as Wydeville) family too. Alice was the first cousin of Elizabeth Woodville, mother of the Princes in the Tower. Alice had also been in Elizabeth’s service during her time as King Edward IV’s queen, so there is a possibility that the boy Richard would have known Alice already. Could we suggest the boy was taken into the care of Sir John Fogge in Ashford so that the boy could live quietly and secretly with his mother’s side of the family?

Sir John Fogge was well-known in Ashford. He helped build Ashford College, a building that still stands today, but is now a part of Ashford’s museum. He is also remembered in our modern-day minds with the naming of a road, Sir John Fogge Avenue. Fogge also built St Mary’s Church, the main church in Ashford’s town centre today, and his resting place is found there. Would anyone question this man taking on a ward, paying for his education or even paying for a career in bricklaying, a job that may not be normally classed for a royal but a job that would have seen the boy financially settled?

With the burial record of a ‘Richard Plantagenet’ of Eastwell Church being known and with Eastwell not being that far away from Ashford in Kent, could we imagine a possibility that instead of the record suggesting King Richard III’s illegitimate son, it was a record of one of King Edward VI’s sons? One of the ‘Princes in the Tower’? Of course, being King Edward’s son, he too would be a Richard Plantagenet?

The thought that one of the ‘Princes in the Tower’ had survived is very tempting to believe. However, at the same time, it is still very debatable, with a DNA test on the bones that were found at the foot of the stairs of the White Tower in the Tower of London not being possible at the moment. Maybe one day we will know, and, in turn, know what, if any, involvement Sir John Fogge, Mary Boleyn’s future grandfather-in-law, had in the matter.

Sir John Fogge passed away on 9th November 1490, and because he had built the main church within Ashford town, St Mary’s, he was buried beneath a grand altar-tomb in that church. Sir John’s tomb was situated in what is now called St Nicholas’ Chapel, however, it was referred to as Repton Chapel in previous years, named after the place in which Sir John Fogge spent his final days: Repton Manor, on the outskirts of Ashford.

If you were to look closely in this church, you might just be able to see a jousting helmet on the wall near his tomb. The helmet once belonged to Sir John Fogge, and he is also celebrated in a memorial window. Sir John’s family still plays an important role within Ashford, as everyone who is baptised at the church uses the font that the Fogge family bought for St Mary’s Church.

This font is quite interesting to look at, now we know a little more about the background of Sir John Fogge. Built within the Tudor period, when codes and symbols meant everything, the font is decorated with the Fogge family’s coat of arms entwined with Tudor roses. This may give us a clue to the connection the Fogge family may have believed they had with the Tudor royal family. This maybe because of Sir John Fogge’s connection to the royals through King Henry VIII through his grandmother, as mentioned within this article, or it may be through another, more later, suggested connection…

The Parr Connection?

Although documents are limited, there is a suggestion that Sir John Fogge and Alice Haute gave birth to another little girl in Ashford in 1469. This would have been eleven years after their marriage and at a time when Sir John had been given the manors of Tonford in Thanington and Dane Court in Boughton under Blean, as well as being presented with a knighthood. Sir John was also given the office of Keeper of the Writs and was the Treasurer of the Household to King Edward IV.5 He, as mentioned before, was also given the role of Chamberlain to the young Prince of Wales Edward. It is possible that the family could indeed afford to give another child a good childhood and education. As the dates of birth for John and Alice’s other children, Anne, Elizabeth and Margaret Fogge differ in different sources, it is difficult to know if this particular baby girl was older or younger than them.

Nevertheless, it is suggested that this child was named Jane, and it is this Jane that married Thomas Greene in 1483 in Norton, Northamptonshire. The couple are said to have had ten children, six sons and four daughters. One of these daughters was Maud Green (or Greene) . This Maud Green is the Maud that was lady in waiting to Katherine of Aragon, King Henry VIII’s first wife, from 1509. It is said that these two ladies got on so well with each other that when Maud gave birth to a baby girl, she named her child Catherine after the queen and Queen Katherine was her godmother. This Catherine, grew up and married four times. One of her husbands was King Henry VIII . This Catherine was Catherine Parr.

If it’s true that the Jane Fogge who married Thomas Greene in 1483 was a child of Sir John Fogge, then not only was his grandchild a lady in waiting to a Tudor queen consort, but his great-grandchild would become a Tudor queen consort herself. This is an interesting concept to think about when we think back to the font paid for by the Fogge family, that has their coat of arms entwined with Tudor roses.

Again, it is all very debatable, with documents being limited to us so far, but what is perhaps most interesting is that through one single marriage, that of Sir John Fogge and Alice Haute, we have family connections to the Woodville and Boleyn families, and, quite possibly, to Catherine Parr. All powerful families that have their own rooted connections that seem to knot themselves around the Tudor Rose of the Tudor dynasty.

About the author

Notes

- D. Baldwin, The Lost Prince – the survival of Richard of York. Stroud 2007.

- Ibid.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-kent-21366578

- The Mistresses of Henry VIII by Kelly Hart. The History Press 2009.

- Elizabeth, England’s Slandered Queen – Arelene Okerlund.

- Douglas Richardson. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study of Colonial and Medieval Families. 2nd Edition 2011.

This is a very interesting article but there’s actually no evidence that any abduction attempt actually happened. The sources are very vague and all they tell us is that certain persons were being punished for an alleged plot to remove the illegitimate sons of Edward iv from the Tower as well as there being rumours that his daughters would be moved from sanctuary. Richard wrote a letter asking for the Great Seal to be given to him in order to act in an emergency and in this letter we learn about these rumours, the possibility of this plot and of the arrest and punishment of those involved in a conspiracy. However, we don’t know if an actual attempt was made on the Tower or that the conspiracy was stopped in its tracks. The entire affair is very odd and mysterious. However, Fogge is one named in this and the Sanctuary Plot and was pardoned by Richard iii. The Sanctuary Plot was of course the plot outlined in Croyland regarding the conspiracy between Margaret Beaufort and Elizabeth Woodville to put Henry Tudor on the throne, via some kind of odd link to the so called Buckingham Rebellion. Margaret was Attained for treason but spared and given into the care of her husband and lost her property. This whole thing was possibly a subplot but again its not clear that any attempt to spring the boys was made..

One thing we do know is that security was increased in London and around the Tower. At least one source places the Princes still in and around the White Tower during the later Summer and early October. Others have them last recorded in August 1483 and one mistakenly said they died while Edward iv was still alive. Mancini dates a change of custody to August and they were then moved further into the Tower compound, which makes sense if in July an attempt at abduction was made or that planned. They were definitely given new servants at the time that Richard left on progress, July 1483, those whom he trusted and their old servants pensioned off. By this time of course they were both illegitimate and Richard was King, so had no right to live in the main Royal Palace. However, the Apartments in the White Tower were perfectly adequate and its here they would have moved to for security, not a dungeon. Its afterwards that the mystery began.

Anyone who claims to actually know what happened to Richard of Shrewsbury and the former Edward V are kidding themselves, because nobody does. Hence the 1001 theories and two dozen suspects. The last person recorded as seeing the Princes alive was Dr John Argentein. He was still visiting them for several weeks at least after they moved out of the Royal Apartments and was one of Mancini’s sources. He tells us Edward was ill, but was it a physical or psychological illness or both and he feared death. Was he depressed, in pain or both? Richard, a complete stranger to his brother, was completely the opposite and apparently untroubled by his surroundings. Where they in any real danger and if so, who from? When they vanished from human sight, what happened to them?

Well of course one theory is that they were moved North and then out of the country. Another was that one remained in the country and assumed a new identity, surviving Bosworth, Henry Vii and even well into the reign of Henry Viii. The mystery of Richard of Eastwell has always had this connection with the Princes, one of whom came to Bosworth, then lived this mysterious and well educated life as a craftsman and was buried as Richard Plantagenet. Was he the son of Edward iv or was he an illegitimate son of Richard iii as he is also referred to? We simply don’t know and we don’t really know how much verification can be given to the story. The Society used to hold regular visits to Eastwell but haven’t done so now for several years. The grave unfortunately, is not in the best shape, but the remains within may well be. With DNA from Elizabeth Woodville’s sisters being sequenced and the known DNA from Richard and his sister Anne, etc, it is now possible to compare the bones, if any exist, at Eastwell and to identify the bones in Westminster. I very much doubt, however, that the bones in Westminster are any relation to any member of the Plantagenets.

The idea of an actual abduction being a success and either Edward or Richard being removed into the custody of Buckingham or a supporter is fascinating, but there is also the tragic possibility that in such an attempt they lost their lives or were killed by an abductor. Did, as has recently been suggested, their bodies vanish as well, which is why they were never shown in public? The possibilities of a successful removal from the Tower of London, either by abduction or the King, are endless. This is why historians like Matthew Lewis believe they survived. They could have been kidnapped, killed in the Buckingham Rebellion, smuggled abroad and returned as a future claimant or been raised under a new identity.

Fogge himself is an interesting character, if a bit shady and his own connections to the important families of the later fifteenth century and the Tudor era are certainly worth reading further. He probably deserves a biography of his own.

It would be great if Queen Elizabeth were to give permission to have the bones in the Westminster urn examined for any DNA connection to the Plantagenets, but I feel she is of the opinion that it is such an old story a medieval whodunnit, and the bones whoever they belonged to should rest in peace, personally I have always found the theory that both princes were spirited away to be very far fetched, they were after all very important prisoners and held in the most impregnable fortress in the land, security would have been very tight.

Hi, Christine, yes, the security arrangements made it impossible almost, although in 1460 the Tower was attacked and the mob got in in 1381, got into the Queen Mother’s apartments and dragged the Archbishop of Canterbury outside to behead him. It wasn’t totally impossible to get inside and it was a busy place, hundreds of people coming and going all day long and even during the night. However, Richard put people he could trust in charge of them before he left, so he obviously tightened things up. If they were moved at all, they were moved by his men and moved North. Richard had his main affinity in the North, he owned plenty of fortresses like Middleham and Pontefract, Carlisle, Knavesborogh, Nottingham, etc, which although luxurious, were also formidable and they could be moved there very easily. A number of documents were destroyed by Henry Vii when he took the throne but there are actual financial accounts which refer to robes and clothing for the Lord Edward and Lord Bastard that may refer to the former Edward V, whose title would now be Lord and not Prince. There were other royal children at Middleham and Pontefract and Sheriff Hutton in the Midlands which are all set up for the care of such children. Elizabeth of York and her sisters were sent to Sheriff Hutton before Bosworth. There are all kinds of hints as to the provision of suitable accommodation and meeting the needs of unnamed special guests or important hostages or privileged young people being made in these places during 1484 and into the reign of Henry Vii. Their identity is being cleverly hidden but its very tantalising as to who they may refer to. I doubt they would be spirited away, although obviously this alleged plot intended to break in and do just that, but moving the boys to a secure but more remote location as a response to an attempt to break them out, that is a definite possibility as is moving them into the more secure parts of the Tower.

The Medieval Royal Palace was against the outer ward with the Saint Thomas Tower being the only surviving part and the White Tower was the secure fortress. Edward I built a Great Hall and the Byward Tower formed part of the other end of several corridors and rooms etc. This was completely altered by the Tudors and replaced and the Garden Tower and White Tower, Great Hall, four Chapels and Queens and Kings Apartments being interlinked and taking up much of the modern green as well. In addition to this there was the armoury, a mint, zoo, private dwellings, workshops, cells, fortifications, etc, gardens, kitchens, the wardrobe, the jewellery house, the wardens house and so on. The Tower was the hub of the City. Dozens of water gates served the great giant and it has outlets to the shore and the sea. It hasn’t always been as careful about comings and goings as it is today. In the fifteenth century it was as much a home as anything else and it’s reputation certainly hadn’t even begun. The Tudors would soon change that but in 1483 there was hardly anything sinister about royal children, legitimate or otherwise living within its walls. The White Tower was the most secure part, its heart, with a massive Norman Church built inside and apartments that were both luxurious and secure. Any real attempt to move the boys would surely meet with resistance, being more likely that any movement was sanctioned and up river, then North and if necessary, abroad to the Netherlands.

Yes the Tower only became a much feared prison in Tudor times before that it was a royal residence, when William the Conqueror began building it it was as a fortress to withstand attacks from invaders, however even though theTudors gave it a sinister and feared reputation, it was still used as a royal residence as they stayed there before their coronations, hence the beautiful lodgings of Queen Anne Boleyn, in the reign of Richard 11 the archbishop Sudbury was beheaded and several prisoners have managed to escape from there, Roger Mortimer for one and others, but the two little princes were very important high ranking individuals therefore I think the stories of them being smuggled out are quite far fetched, it does have a grim history, Henry V1 was murdered there and there are the chambers where the instruments of torture are kept, Scavengers Daughter The Little Ease for example, amongst others and the most feared one of all – the rack, but yes it was also an armoury and still today houses the Crown Jewels, although I have heard that they maybe replicas, there was a scare when Captain Blood managed to steal them in the rein of Charles 11, but that most benevolent and merciful of monarch’s pardoned him saying if he was clever enough to steal them, then he should not be punished, Charles really was a unique monarch! It has also been a managerie and there are illustrated prints dating from Victorian times showing crowds visiting the exotic animals in their cages, in fact one of the animals, the ghost of a bear has been reported being seen down the years, today a visit to the Tower makes a nice day out, I have been twice once with my parents after I’d come out of hospital when I was seventeen, and then years later with my sister who told me she had always wanted to go there, it does make me laugh though, listening to the beefeaters when they regale the crowds of the blood thirsty executions that used to take place there, as they always embroil them somewhat, and in fact the plaque that marks the scaffold site is not correct, it stood some way away, it’s such a pity that Anne Boleyn’s lodgings were pulled down because it would be wonderful to visit them, sadly many places of historical importance have vanished down the years.