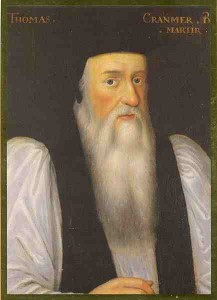

On this day in history, 21st March 1556, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer was executed, he was burnt at the stake as a herectic, one of the Protestant martyrs of Mary I’s reign and one of the three famous “Oxford Martyrs”.

This article has been split into two parts – The Life of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and the Execution of Thomas Cranmer.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer Bio

Born: 2nd July 1489 in Aslockton, Nottinghamshire, England.

Died: 21st March 1556, executed at Oxford by being burnt to death. Cranmer was one of the Oxford Martyrs along with Bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley who were burnt at the stake in Oxford on the 16th October 1555. The burnings took place to the north of the city of Oxford where the present Broad Street is now located.

Memorial: A cross-shaped cobbled area just outside the front of Oxford’s Balliol College marks the spot where the Oxford Martyrs were burnt at the stake and the Martyrs’ Memorial located at the southern end of St Giles’, at the intersection with Beaumont Street and Magdalen Street, commemorates the deaths of Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley. It was designed in 1838 and was completed in 1843, and is a spire with statues of the three men who died. The inscription on the memorial reads:-

“To the Glory of God, and in grateful commemoration of His servants, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Prelates of the Church of England, who near this spot yielded their bodies to be burned, bearing witness to the sacred truths which they had affirmed and maintained against the errors of the Church of Rome, and rejoicing that to them it was given not only to believe in Christ, but also to suffer for His sake; this monument was erected by public subscription in the year of our Lord God, MDCCCXLI”.

Family Background: Thomas Cranmer was the son of Thomas Cranmer and his wife Agnes (nee Hatfield). He had an older brother, John, and a younger brother, Edmund.

Education: When Cranmer was 14, after the death of his father, he went to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he studied for a Bachelor of Arts degree, which took him 8 years. His degree consisted of logic, philosophy and classical literature, and he followed it with a Masters degree studying the humanists. After obtaining his Masters degree in 1515 he was elected to a Fellowship of Jesus College.

Marriage: Cranmer married his wife Joan after completing his Masters degree and was forced to relinquish his fellowship, due to his marriage. He therefore became a reader at one of the other Cambridge colleges. Sadly, Joan died in childbirth.

Cranmer met and married his second wife, Marguerite, in July 1532 when he was working as ambassador to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Cranmer was friends with Marguerite’s uncle (by marriage), Andreas Osiander, a Nuremberg reformer. Although Cranmer was a priest, he did not take Marguerite as his mistress, instead he decided to set aside his vow of celibacy and marry her.

Early Career: After the death of Joan, Jesus College reinstated Cranmer as a Fellow and Cranmer began studying theology at the college. In 1520 he went into holy orders and in 1526 he was awarded a Doctorate of Divinity.

From 1527, as a reputable university scholar, Thomas Cranmer was involved in assisting with the proceedings to get Henry VIII’s first marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled and it was he who suggested to Edward Foxe and Stephen Gardiner, in 1529, that they should canvass the opinions of university theologians throughout Europe, rather than just relying on a legal case in Rome. The King liked the plan and Cranmer was chosen as a member of the team to gather these opinions. Under Edward Foxe, the team at Rome produced the Collectanea Satis Copiosa (“The Sufficiently Abundant Collections”) and The Determinations, which supported, both historically and theologically, the idea that Henry VIII as king exercised supreme jurisdiction within his realm.

In 1532, Thomas Cranmer was appointed as ambassador at the court of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and it was in this role that he saw the effects of the Reformation in cities like Nuremberg and met his wife, Marguerite. He was, however, unable to persuade Charles V to support Henry VIII’s annulment from Catherine of Aragon, the Emperor’s aunt.

Cranmer’s Influences: In his Bachelor of Arts degree, Cranmer studied the works of Erasmus and Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples. In 1531, Cranmer became friends with Simon Grynaeus, a humanist based in Basel, Switzerland, and it was this friendship which led to Cranmer’s later contacts with Continental Reformers from Strasbourg and Switzerland. He became friends with Martin Bucer, a continental reformer, through 18 years of correspondence, finally meeting when Bucer fled to England from Strasbourg in 1549.

Archbishop Cranmer: In the Autumn of 1532, while in Italy, Thomas Cranmer received a letter dated the 1st October 1532 informing him that he was the new Archbishop of Canterbury, due to the death of William Warham, the former archbishop. Cranmer was ordered home to England to take up his new position, one which had been arranged by Anne Boleyn and her family. Cranmer arrived back in England in January 1533 and was consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury on the 30th March 1533, after the arrival of papal bulls which were needed for his promotion from priest to Archbishop.

The Annulment: The new archbishop worked closely with his King on the annulment proceedings. Anne Boleyn was already pregnant and the couple had secretly married in January 1533 so the annulment was now considered urgent. On the 10th May 1533, Archbishop Cranmer opened court for the annulment proceedings. Catherine of Aragon did not attend and the King was represented by Stephen Gardiner. On the 23rd May, Cranmer ruled that the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon was against the will of God, the marriage was declared null and void. 5 days later, on the 28th May, Cranmer declared the marriage between Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn valid and on the 1st June he crowned Anne Boleyn Queen of England and in September 1533 he had the pleasure of baptising the couple’s daughter, Elizabeth, and becoming her godfather.

Cranmer and Cromwell: Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister, was forced to intervene when Bishops Gardiner, Longland and Stokesley complained about Cranmer’s role and power. Cromwell became Vice-gerent, the deputy supreme head of church affairs under the King, thus putting himself ahead of Cranmer and pleasing the other bishops.

The Fall of Anne Boleyn: It seems that Cranmer was unaware of Anne’s fall and the King’s interest in Jane Seymour until Anne was arrested on the 2nd of May 1536. Cranmer wrote to Cromwell in support of Anne but his letter did no good, her fall was a foregone conclusion. On the 16th May, Cranmer heard Anne’s confession at the Tower of London and on the 17th May he declared that her marriage to the King was null and void. Anne Boleyn was beheaded on the 19th May 1536.

The Fall of Anne Boleyn: It seems that Cranmer was unaware of Anne’s fall and the King’s interest in Jane Seymour until Anne was arrested on the 2nd of May 1536. Cranmer wrote to Cromwell in support of Anne but his letter did no good, her fall was a foregone conclusion. On the 16th May, Cranmer heard Anne’s confession at the Tower of London and on the 17th May he declared that her marriage to the King was null and void. Anne Boleyn was beheaded on the 19th May 1536.

The Ten Articles: In the summer of 1536, Archbishop Cranmer’s “Ten Articles” were finally published, after much debate between the conservatives and reformers. These Ten Articles defined the beliefs of the new Church of England, the Henrician Church which had been established after the break with Rome. The first five articles explained that the new church recognised only three sacraments, those of baptism, the eucharist and pennance, and the second five articles were concerned with the roles of purgatory, saints, rites and images, and were more conservative in flavour to balance out the reformist first five articles. It was these articles that caused the Northern uprising known as The Pilgrimage of Grace.

The Bishops’ Book of 1537: This book, also known as “The Institution of the Christian Man” was written by a team of 46 divines headed by Cranmer to rectify the inadequacies of the earlier “Ten Articles”. It set out the religious reforms of Henry VIII and established the new Ecclesia Anglicana, the Church of England.

The Act of the Six Articles: This Act of 1539 reversed some of the reforms and reaffirmed traditional Catholic doctrine on transubstantiation, the withholding of the communion cup from the laity, clerical celibacy, the vows of chastity, permission for private masses and the importance of auricular confession. As a result of this Act, Cranmer was forced to send his wife and children abroad for safety.

Cranmer and the Downfall of Catherine Howard: In June 1541, Henry VIII left Cranmer, Thomas Audley and Edward Seymour in charge as a council while he went on a royal progress with his fifth wife, Catherine Howard to the north of England. It was during the King’s absence that the council became aware of Catherine’s colourful past and possible extramarital affairs. Audley and Seymour chose Cranmer to be the one to tell the King and Cranmer did so by giving the King a letter during mass. Catherine Howard was executed in February 1542.

1543-1547: Cranmer survived a plot by clergymen in 1543 and the King gave him his full support. When Cranmer was arrested in the November, he was supported by the King and the two of the ringleaders of the plot were sent to prison and Stephen Gardiner’s nephew, Germain Gardiner, who had been heavily involved, was executed.

In 1544, on the 27th May, Cranmer’s Exhortation and Litany was published, the first officially authorised liturgy in English which is still part of the Book of Common Prayer today.

On the 28th January 1547, Henry VIII died. While he was dying, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer held his hand and gave the King a reformed statement of faith instead of the usual last rites. Cranmer showed his grief for his master, the King, by growing a beard which was also a symbol of his rejection of the old church and its ideas.

The Reign of Edward VI: Thomas Cranmer was one of the executors of Henry VIII’s will and so was an important of the Lord Protector’s (Edward Seymour’s) administration. In August 1547, each parish was instructed to obtain a copy of “The Homilies”, a book of twelve homilies, four of which were written by Cranmer. The 1549 Act of Uniformity established “The Book of Common Prayer”, which set out the new legal form of worship in England. It was made compulsory in June 1549 which led to the Prayer Book Rebellion, a series of revolts in the south-west of England which then spread into the east of England. The rebels called for the rebuilding of abbeys, the restoration of the Six Articles, the restoration of prayers for souls in purgatory, the policy of only the bread being given to the laity and the use of Latin for the mass. On the 21st July, Cranmer preached a sermon at St Paul’s Cathedral defending the church line and the Book of Common Prayer.

Although the Prayer Book of Rebellion was squashed, it did have a negative effect on the Lord Protector’s administration and in October 1549, despite Cranmer supporting Seymour, John Dudley took over Seymour’s role. Cranmer was unaffected by this change in government and he continued to work with his friend Martin Bucer on the Ordinal, the liturgy for the ordination of priests, which was published in 1550. Cranmer also went on to publish “The Defence of the True and Catholic Doctrine of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ” in 1550 and in 1552, despite a breach between Cranmer and Dudley caused by the execution of Edward Seymour, Cranmer worked on revising the Prayer Book and canon law and also forming a statement of doctrine. His canon law bill came to nothing but the 1552 Act of Uniformity replaced the Book of Common Prayer with a more Protestant Book of Common Prayer and The Forty-Two Articles were issued on the 19th June 1553. However, the Forty-Two Articles were never properly authorised as some bishops opposed them. Cranmer was working on getting bishops to subscribe to them when King Edward VI died and scuppered all of these plans.

1553-1556: On the 6th July 1553 Edward VI died leaving his throne to Lady Jane Grey who he had appointed his successor in his “Device for the Succession”, which also excluded his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, as heirs to the throne. Thomas Cranmer had opposed the documents but had reluctantly signed them when Edward had asked him to respect his will. Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed Queen after Edward’s death but her throne was seized by Mary I in mid July. Although John Dudley and other members of council were imprisoned, Cranmer was not and on the 8th August 1553 he performed the Protestant funeral rites as Edward VI was buried in the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey. While other reformed clergy fled the country now that the Catholic Mary I was in control, Cranmer chose to stay but after proclaiming that “all the doctrine and religion, by our said sovereign lord king Edward VI is more pure and according to God’s word, than any that hath been used in England these thousand years”, he was ordered to stand before the Queen’s council on the 14th September in the Star Chamber. He was then sent to the Tower of London.

Continued in “The Execution of Thomas Cranmer”.

Sources

- Wikipedia – article on the life of Thomas Cranmer

- http://englishhistory.net/tudor/pcranmer.html – An account of the burning of Thomas Cranmer by an anonymous bystander

- Wikipedia – article on Death by Burning

- YouTube Channel of littlemisssunnydale