In today’s post, Teri Fitzgerald continues her examination of the family of Thomas Cromwell, the protagonist of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, by looking at Cromwell’s nephew Richard Cromwell. Thank you to Teri for a wonderful series of articles, I know I’m enjoying them.

Richard Williams alias Cromwell, was born around 15101 in the parish of Llanishen, Glamorgan,2 to Morgan Williams and Katherine Cromwell, daughter to Walter Cromwell and the elder sister of Henry VIII’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell.3 Richard’s father Morgan Williams, a brewer with holdings in Putney by 1495 and Greenwich in 1517, was the son of William Morgan ap Howell of Whitchurch near Llandaff, Glamorgan, who had been a gentleman of the Privy Chamber to Henry VII.4 When Thomas Cromwell made his will in July 1529 his nephew, whose parents were now dead, was included among his kinsfolk.5 Richard was then in the service of Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset (father of Henry Grey, and grandfather of Lady Jane Grey). Following Dorset’s death in October 1530, Richard joined his uncle’s household at Austin Friars and while in his service was introduced at Court. He adopted the name of Cromwell and for the next ten years, as Richard Cromwell alias Williams, he acted as a trusted agent for the minister, often joining with him in offices and grants. He was appointed joint keeper of Marwell park, Hampshire in 1533, keeper of Orwell park, Cambridgeshire in 1534 and was given a place on the commission of sewers in Huntingdonshire in July 1534. He was constable of Berkeley castle, Gloucestershire (jointly with his uncle) from 1535 to 1540 and solely from 1540 to 1544; sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire from 1536 to 1537 and again in 1541; justice of the peace for Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire from 1538 to 1544. By 1539 he had been made a gentleman of the privy chamber.6

His uncle’s plan in 1533 for his marriage to Catherine St. Leger, the widow of George Courtenay, appears to have been thwarted by her kinswoman Queen Anne Boleyn.7 Sir William Courtenay, her father-in-law, had naturally been cautious when the match was proposed to him by Thomas Cromwell:

“I desire you to obtain the King’s letters of request to me therefor to be directed, in the avoiding of her Grace’s displeasure.”8

The young widow would instead marry John Zouche, a younger son of John Zouche, 8th Baron Zouche and kinsman of George Zouche who was married to Anne, Lady Zouche (née Gainsford), a favourite lady-in-waiting of the Queen. Within a few months, however, Thomas Cromwell had successfully negotiated with Sir Thomas Denys for a marriage between Richard and his step-daughter. By 8 March 1534, Richard had married Frances Murfyn (c.1519 – c.1543), the daughter of Thomas Murfyn and his second wife, Elizabeth Donne. Thomas Murfyn, an alderman and former Lord Mayor of London, had died in 1523 and his widow subsequently married Sir Thomas Denys, a friend of Thomas Cromwell, in 1524. His wife’s ample dowry included houses in St. Helens Bishopsgate and Stepney. The couple had two sons: Henry, (c. 1537 – 1604) and Francis (c. 1541 – 1598).9

“A right hand man of the mauler of the monasteries.”10

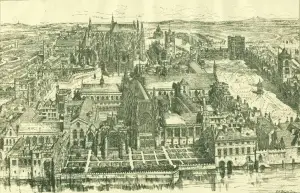

In 1534 he escorted the beleaguered Thomas More, then in the custody of the abbot of Westminster, to the Tower of London.11 Richard’s zeal in visiting and suppressing monasteries made him a target for the rebels of 1536. His involvement in the suppression of the Pilgrimage of Grace commended him to the king as it certainly had with the Duke of Suffolk and Sir William Fitzwilliam and he was suitably rewarded for his loyalty with royal grants. By the end of the Northern revolt and its aftermath, Richard had begun to take a more prominent role at court and its ceremonials. He and his cousin Gregory carried banners in the funeral procession of Queen Jane in November 1537. He bought Sawtry abbey from the crown for £1,700 in 1537 and then added further monastic property, including Ramsey abbey for which he paid nearly £5,000. It was Hinchingbroke priory, which he leased in March 1538 that he was to make his home. His son and heir, Henry, would later divide his time between the two properties, using Ramsey as a summer residence. At Hinchingbrooke he pulled down the convent and built a house, using materials from Barnwell Priory. It was here that he was knighted by Elizabeth I after her visit in 1564. Henry was known as ‘The Golden Knight’ because he threw coins from his coach to the people in the streets as he moved from Hinchingbrooke to Ramsey for the summer months.12

A tournament was held at the palace of Westminster in May 1540 where Richard would distinguish himself in the presence of the King.13 The jousts had been proclaimed in France, Flanders, Scotland and Spain for all who would come up against the challengers of England: Sir John Dudley, Sir Thomas Seymour, Sir Thomas Poynings, Sir George Carew, Anthony Kingston and Richard Cromwell (who would both be knighted on the second day of the jousts). The forty-six defendants, who jousted against them on May Day were led by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey and included: Lord William Howard, Edward Lord Clinton (later Earl of Lincoln) and Richard’s cousin, Gregory Lord Cromwell. The jousts, which also involved a great deal of feasting at Durham Place, commenced on May Day and ran over the course of several days. The English competitors were richly dressed, their horses trapped in white velvet and their attendants dressed in white velvet and sarcenet. On the second day of the tournament Richard defeated two foreign knights and so impressed the king that he knighted him on the spot, exclaiming:

“Formerly thou wast my Dick, but hereafter shalt be my diamond.”

His Majesty then dropped his diamond ring for him and thereafter Sir Richard Cromwell and his descendants adopted as their crest a lion rampant holding up a ring in his right paw.14 (see image below – WILLIAMS alias CROMWELL, of Hinchingbroke in Huntingdonshire, Knight. Sable, a lion rampant Argent, holding in his dexter paw a ring Or. Crest, a demi lion rampant Argent, holding a ring as in the arms. Motto. SUDORE NON SUPORE. By activity not sloth.15)

Sir Richard went on to unhorse Mr Palmer on the third day and he defeated the soon-to-be infamous Thomas Culpeper, gentleman of the Privy Chamber on the fifth day of the tournament. On the seventh of May the challengers were all rewarded by the king with an annual income of a hundred marks, granted out of the dissolved monastery of Stamford, and with houses to live in.

“I never more desired anything than, since your departure, to see you, nor thought time longer in your absence.” – Richard Cromwell to his uncle, 153916

From the mid-1530s he had begun to establish himself as a major landowner and power in the county of Huntingdonshire and by 1539 his position in the shire would have needed little reinforcing by his uncle and which gave him precedence over his fellow-knight Oliver Leder, a dependant of the minister. Richard was joined in the House of Commons in 1539 by his cousin Gregory Cromwell, with whom during summer of 1540 he had to witness the attainder and execution of their kinsman. He and his cousin had been particularly close to the Earl of Essex and benefitted greatly from his rise to power. However, both men would emerge from this catastrophe relatively unscathed and would remain on very close terms. After his uncle’s death Richard reinvented himself as Richard Williams alias Cromwell, a wise decision given the circumstances. In 1541 Richard was appointed sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire for the second time. He would continue to accumulate property and by the time of his death was one of the wealthiest men in England with land holdings in several counties.

During the last four years of his life Richard consolidated his Huntingdonshire estates and sold off property elsewhere. He was again elected first knight of the shire in the Parliament of 1542 and in the summer of 1543 he served in the campaign in the Netherlands, where he saved the life of the commander, Sir John Wallop. He was in England again early the following year but in the summer of 1544 he accompanied the King’s expedition to France.17

Richard’s wife, Frances was still living in June 1542,18 but had died before he made his will on 20 June 1544. He died on the 20 October at Stepney and was buried at St Helen’s Church, Bishopsgate.19 He had been in ‘most health’ before his departure for France, and his death may have been the result of the French campaign which had ended a month earlier. After providing for his sons and leaving horses to the King, Sir John Williams and his cousin Gregory Cromwell, he had instructed his executors to settle his debts amounting to £3,000 with the income from the remainder of his property. His kinsman Sir Edward North acquired the wardship of his seven year-old son and heir Henry, who was to become the grandfather of the Protector, Oliver Cromwell.20

Click here to read our other Real Wolf Hall articles.

References

- Robertson, Mary Louise. Thomas Cromwell’s servants: the ministerial household in early Tudor government and society [PhD thesis]. Los Angeles, 1975. p. 474.

- Leland, John. The itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543. [ed.] Lucy Toulmin Smith. London, 1906. vol. III, p. 17.

- Hofmann, T. M. Cromwell, alias Williams, Richard (by 1512-44), of London; Stepney, Mdx. and Hinchingbroke, Hunts. [ed.] S. T. Bindoff. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558. 1982.; Noble, Mark. Memoirs of the Protectoral House of Cromwell … 3rd edn. London, 1787. vol. I, pp. 238-40.

- Nicholas, Thomas. Annals and antiqities of the counties and county families of Wales … London, 1872. vol. II, pp. 589-90.

- Merriman, Roger Bigelow. Life and letters of Thomas Cromwell. Oxford , 1902. vol. I, pp. 56-63.

- Hofmann.

- Ives, Eric. The Life and death of Anne Boleyn: the ‘moost happy’. Oxford, 2005. p. 210.

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII. vol. 6, 837.

- Hofmann.

- Nicholas, p. 589.

- Roper, William (2003). Wegemer, Gerard B.; Smith, Stephen W., eds. The Life of Sir Thomas More, c.1556, 2003, pp. 42-3

- Fuidge, N. M. Cromwell, alias Williams, Henry (c.1537-1604), of Hinchingbrooke and Ramsey Abbey, Hunts. [ed.] P. W. Hasler. The history of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558-1603. 1981.

- Wriothesley, Charles. Hamilton, William Douglas, ed. A chronicle of England during the reigns of the Tudors: from A.D. 1485 to 1559. London, 1875. vol. I, pp. 116-9.

- Cox, John Edmund. The Annals of St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate. London, 1876. p. 242.

- Motte, Philip de la. The principal, historical, and allusive arms, borne by families of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with their respective authorities. London, 1803. p. 498.

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII. vol. 14, pt 2, 290.

- Hofmann.

- A history of the county of Huntingdon. Page, William, [ed.]. London : Victoria County History, 1932, vol. 2, pp. 198-201, fn. 52.; Cox, p. 243. Date of death is incorrect. Frances was still living in 1542.

- The New England historical and genealogical register. 1897, repr. 1998, vol. 51, p. 211. Frances was still living in June 1542. Richard died in 1544 not 1547.

- Hofmann.