“Judging by the reactions to the BBC’s six-part adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s ‘Wolf Hall’ and ‘Bring Up the Bodies’, the contest over the legacies of More and Cromwell is as bitter as ever and damaging to serious widespread engagement with this crucial period as ever.”

_ Paul Lay, editor of History Today magazine1

In the BBC’s visual feast, Wolf Hall, Thomas Cromwell is portrayed by Mark Rylance as a gentle family man and Thomas More (played by Anton Lesser) as a nasty piece of work. This stunning reversal of their traditional roles has generated a great deal of behind the scenes sniping, which is almost as entertaining as the series itself. In an interview with Radio 5 Live, David Starkey, historian and television presenter, who “knows history”, and despite not having read Hilary Mantel’s books (Wolf Hall, Bring up the Bodies) or seen the series, claims that Mantel’s depiction of Thomas Cromwell as a loving father is “total fiction.” Thomas More, he says, “really did have these affectionate relations with his children… in other words, as I understand it, it is based on a deliberate perversion of fact.”2

Simon Schama, while not denying the possibility that Thomas Cromwell was “a good family man” asserts that this didn’t have any bearing on his character: “Sure, he was a good family man. So was Himmler.”3

It would seem that that the propagandist historians have done their work well! Even Holbein’s unflattering portrait of Cromwell in the Frick Collection provides ‘evidence’ that Cromwell was a complete rotter, at least according to art historian and television presenter, Waldemar Januszczak.4 It should be noted that in this author’s opinion More’s portrait in the Frick collection isn’t too pretty either!

“The problem with historical fiction is that it needs heroes. History doesn’t.”

According to David Starkey, “Both men believed in the idea of enforcing ideas on others by persecution and execution. They only disagreed which ideas.”5 In a curious parallel, each of their sons has been lampooned by successive writers in an attempt to discredit their fathers: John More has been described as “little better than an idiot”6 and Gregory Cromwell as “almost a fool”7 despite evidence to the contrary. Thomas More’s friend, Erasmus, described John More as “a youth of great hopes”, adding “that it is no use either to exhort him to the study of letters or the practice of virtue, since he was himself so well disposed…”8 Thomas More himself, in a letter to his daughter in 1534, described Cromwell’s son, Gregory as “a goodly young gentleman, and shall I trust come to much worship,”9 and the Duke of Norfolk assured Gregory’s father in 1536 “Be sure you shall have in him a wise quick piece.”10

Why should one man always be lauded and the other vilified? Both men had admirable qualities as well as flaws. It’s time to let go of the usual stereotypes and adopt a more balanced approach in the assessment of historical figures. The hagiographic depiction of Thomas More in Robert Bolt’s A Man for all Seasons played by Paul Scofield has “ruled the roost for 30 or 40 years now,” says Diarmaid MacCulloch, professor of church history at Oxford University, who is working on his own biography of Thomas Cromwell, and it’s time for a different view. 11

Is the depiction of Thomas Cromwell and his family in Wolf Hall “total fiction” as David Starkey claims? Was Cromwell the loving husband and father portrayed by Hilary Mantel, or does Thomas More alone merit the description as the good family man? It appears that Hilary Mantel is on the money, and David Starkey’s assumption that there is no evidence that Cromwell was a loving father or that his son Gregory had an education that was at least equal, if not superior to that of Thomas More’s son, John doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. No letters from Cromwell to his son have survived, however a number of affectionate letters from Gregory to his father, as well as letters from those appointed to supervise the boy’s care and education during his youth, support Mantel’s depiction of Cromwell as a devoted father and outline Gregory’s extensive education, which included Latin, French, history, mathematics and music.12

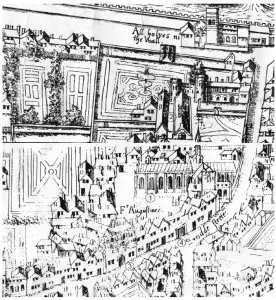

1 – Church and churchyard

2 – Cloister wings

3 – Thomas Cromwell’s house

4 – Main gate

By the 1520s, Thomas Cromwell was a successful merchant and lawyer living with his family in an imposing home surrounded by gardens in Austin Friars. Monastic houses in London often leased land within their precincts to secular tenants, and Austin Friars was no exception. Several tenements were built on the western side of the precinct and the friary also owned a number of properties just outside the precinct, adjoining Throgmorton Street, which included the Swanne and Bell inns. The larger tenements were rented to important officials and dignitaries; in the first half of the sixteenth century their tenants included Thomas Cromwell, the wealthy Italian merchant John Cavalcante, the Holy Roman Emperor’s ambassador Eustace Chapuys, the French ambassador, and Erasmus, who left without paying his bill.15

Elizabeth Cromwell (played by Natasha Little) was the daughter of John Wyckes of Putney, and his wife Mercy (played by Mary Jo Randle.17 Probably in late 1514 or early 1515, she married Thomas Cromwell, who had recently returned to England from Antwerp. By 1528 Thomas and Elizabeth had three children: Gregory (played by Tom Holland), Anne (played by Emilia Jones), and Grace (played by Athena Droutis).18

The only surviving letter from Cromwell to his “well beloved” wife in 1525 suggests a normal, happy marriage.19 The letter reveals a dutiful husband, not only requesting news, but also providing meat for the table, a “fat doe” that he had shot himself while out hunting.20

Elizabeth died towards the end of 1528, followed by her daughters Anne and Grace, not long after her husband made his will. That Thomas Cromwell never remarried suggests that he felt his wife’s loss deeply.

Cromwell’s sister-in-law Johane (played by Saskia Reeves) appears to have died not long after Cromwell made his will. Her husband, John Williamson acted as his agent until 1540. There is no evidence to suggest that Cromwell had an affair with his sister-in-law, although it’s an intriguing storyline.

Cromwell’s mother-in-law, Mercy (played by Mary Jo Randle) married firstly Henry Wyckes (Elizabeth’s father) a well-to-do clothier from Putney and later wed John Pryor.23 Mercy and her second husband were living in Cromwell’s household at Austin Friars by 1524, although he had died before July 1529.24

A respected member of the community, the widowed Mercy was still living in the early 1530s and it was one of her servants, Ellen Mitchell, whom Cromwell’s secretary, Ralph Sadler would marry. Unusually for the times, he married for love, not personal advantage, and this impetuous decision would have unfortunate consequences.25

By the time of his death in 1551, he was one of the wealthiest landowners in the Midlands. Richard Cromwell, a favourite of Henry VIII and admired for his military skill and gallantry, held several lucrative posts under the Crown and, by 1539, had been made a gentleman of the privy chamber.26 When he died in 1544, he was one of the wealthiest men in England, with land holdings in several counties. Ralph Sadler, an able and trusted royal servant, although never ennobled, amassed a vast fortune and was at his death in 1587, reputedly the “richest commoner in England.”

Notes and Sources

- P. Lay, “No More Heroes: Thomas Cromwell and Thomas More,” History Today, 26 Feb. 2015.

- “Starkey on Wolf Hall: ‘a deliberate perversion of fact’,” BBC Radio 5 Live: In Short, 26 Jan. 2015.

- S. A. Harris, “Wolf Hall’s Thomas Cromwell was really a ‘bullying monster’ says Simon Schama,” Express, 14 Feb. 2015.

- W. Januszczak, “The true face of the Tudors,” The Sunday Times, 21 Dec 2014.

- P. Stanford, “Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner,” The Telegraph, 20 Jan. 2015.

- E. W. Brayley, Londiniana: or, Reminiscences of the British metropolis …, vol. iv, London: Hurst, Chance, and Co., 1829, p. 62 (footnote *).

- H. Robinson, Ed., Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation, vol. i, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1846, pp. 202-3.

- Brayley

- E. F. Rogers, Ed. “St Thomas More: Selected Letters,” p.222, 1961

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, vol xi, 233.

- V. Thorpe, “Thomas More is the Villain of Wolf Hall. But is he getting a raw deal?,” The Guardian, 18 Jan. 2015.

- H. Ellis, Ed.“Original Letters Illustrative of English History. third series,” vol. i, pp. 338-343, 1846.

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, vol. iv, 5772.

- R. B. Merriman, Life and letters of Thomas Cromwell, vol. I, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1902, 56-63.

- N. Holder, The Medieval Friaries of London: A topographic and archaeological history, before and after the Dissolution (PhD thesis), London: Department of History, Royal Holloway, University of London, 2011, pp. 157-160.

- Ibid., p160

- J. Phillips, “The Cromwell Family,” The Antiquary, vol. ii, p165, 1880.

- Merriman, pp. 56-63

- P. Van Dyke, Renascence Portraits, London: Archibald Constable and Co., 1906, pp. 140-146.

- Merriman, p.314

- Van Dyke, pp. 140-146.

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, iii,3015; iii, 5034; iv, 1385.

- Merriman, p12.

- Ibid.

- “Family of of Sir Ralph Sadler,” The Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. IIII, pp. 260-264, Jan. to Jun. 1835.

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, vol. xi, 31.