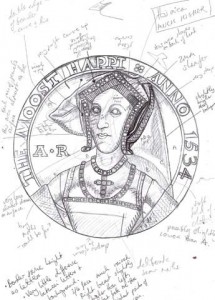

Lucy Churchill has just started selling replicas of Anne Boleyn’s 1534 Moost Happi Medal, so I thought it would be good for Lucy to explain how this beautiful replica came to be made. Over to Lucy…

The original Moost Happi medal is a single issue lead prototype of what is believed to be a commemorative coin. It was made in 1534, the year after Henry VIII and Anne’s marriage, her coronation as Queen of England, and the birth of their daughter Elizabeth. Pregnant again, it was confidently presumed that Anne would give birth to a son. However, the pregnancy failed and Anne’s position became increasingly difficult until, in May 1536, she was beheaded at the Tower of London. This small (38mm in diameter) lead disc is a lasting testimony of the time when Anne was at her most secure and triumphant.

My background, and how I became interested in the Moost Happi medal

I began my career working in museums. Daily contact with ancient, beautiful and interesting artifacts gave me itchy fingers and I was inspired to retrain as a stonecarver. Staying close to my roots I specialised in making historically accurate recreations for restoration work. This is both challenging and satisfying as you must learn to read visual clues from eroded or broken fragments. It is also crucial to subdue your own artistic impulses to recreate the authentic style of the object, whether it be Classical, Gothic, or Victorian Gothic (there is a discernible difference, believe me). Furthermore, we are trained to work to an accuracy of quarter of a millimeter.

Working with ancient buildings encouraged my love of history, and in recent years this became increasingly focused on the Tudors – particularly the controversial figure of Anne Boleyn. I was fascinated to learn that there was only one portrait of Anne Boleyn remaining that was made during her lifetime, and whose identity was undisputed: ‘The Moost Happi. Anno 1534’ medal. (British Museum’s Coins and Medals Collection). However, as a portrait its value was dismissed by many historians because of it damaged condition; the soft lead has been compressed and worn in parts. Most noticeable is that one of Anne’s eyes is obscured, and her nose has been flattened. This makes the portrait seem clumsy and gives Anne an ugly appearance.

I inspected the medal in great detail and realised that beneath the superficial damage there remains a great quantity of finely observed and modeled detail. For example, having studied the pattern of the jewels on the billiment of the gable hood and the diamond weave of the cloth, it was possible to identify the very same headdress and necklace (with a different pendant) in Holbein’s portrait of Jane Seymour. The matching necklace, worn by Anne in the medal with a jeweled cross, can also be found in portraits of Catherine Howard and Katherine Parr. It is also the same necklace worn in the disputed Nidd Hall portrait of Anne. With my professional training and personal interest, I felt compelled to take on the challenge of reconstructing the damaged features and issue the medal of Anne Boleyn as she had wanted to present herself.

My research for the medal reconstruction

I made an appointment to view the object at the British Museum where it is now kept in storage. In the meantime I enlarged the photograph of the medal which is on the museum’s database. Using a light-box I traced those features which could still be seen, resulting in an accurate template of the coin in its current state. I took multiple copies of this line drawing with me to the British Museum, plus measuring equipment such as calipers, dividers and sinking squares – and a very powerful magnifying glass. With the original medal in my hand I annotated copies of the line drawings with written measurements, shading and numerous notes to record its three-dimensional appearance.

Holding the lead medal in my latex-gloved hand was a powerful and moving experience; Eric Ives wrote ‘Such a piece can only have been prepared on royal authority.’ (‘The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn’, Chap 3, pg 31). It is possible that Anne never actually saw this lead version of her portrait. However, knowing that she paid meticulous attention to detail regarding her public presentation, it is plausible that she would have inspected this prototype of the medal. I felt very conscious that I had to do my very best with the reconstruction – not just to record the details in a professionally accurate manner, but to capture the spirit of its original, so that it would be seen as Anne intended.

The reconstruction process

Armed with first hand information, I set about recreating the object. I decided to reconstruct the medal at four times the original scale, so as to display its features more clearly. At this stage I was motivated solely by personal curiosity and had no intention to make copies to sell. Therefore it was a personal decision based on what would look best on my desk, or mounted nearby on the wall. In this my original intention has been fulfilled and while I do my deskwork, Anne’s smiling face inspires me daily.

Using a needle to prick holes along the traced lines of the medal, I was able to accurately transfer the information onto a rolled out disk of modeling wax. This gave me a ‘footprint’ which I could then build onto using tiny wooden and metal sculpting tools and my fingers. I referred to the notes and sketches I had made at the British Museum to guide me regarding the relative height of the modeled features. Despite working at a larger scale than the original sculptor, it was a challenging task. Unlike the original sculptor, I had the advantage of being able to work with powerful magnifying equipment. However, the heat of the lamp softened the wax so I had to take care not to inadvertently touch (and damage) areas that were already complete.

When the reconstruction was finished I took it to Steve Cole at Articole Studios – www.articolestudios.co.uk – who coated the wax model with silicon rubber. This made a negative form which captured every detail of the modeled form, so that copies could be made in a more durable material. It was incredibly exciting to come back a few weeks later and to be able to hold the reconstruction, now cast in bronze resin, in my hands.

Critical responses to the Moost Happi reconstruction

I was elated that historians such as Alison Weir and David Starkey praised the authenticity of my reconstruction. However, the response that meant the most to me came from the late historian Eric Ives; “Lucy Churchill’s brilliant achievement has brought us as close to the real Anne Boleyn as we shall ever be able to get.”

I hope very much that Anne would approve and be satisfied that her Moost Happi medal has been issued at last.

Lucy Churchill, BA (Hons)

November 2012

Cambridge, England.

Lucy’s replica medal is available at – http://www.lucychurchill.com/MoostHappyBuynow.php.

I would LOVE to have this in a smaller size on a pendant! *hinthint*

I know that Lucy has been looking into doing it in a smaller size.

It’s beautiful, it’s on my Christmas shopping list!

An excellent reconstruction!

Mine is hanging on the wall in front of my writing desk.

What an achievement! It really is wonderful–congratulations for such an excellent recreation. Yes, it’s on my wish list!

This is wonderful! What an accomplishment.

Is anyone else amazed also by the resemblance of this medal to the Holbein sketch? The chin, lips, cheeks, forehead…I believe we may be closer than ever to the real Anne.

https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/17017/the-holbein-sketch-is-it-anne-boleyn/

Leslie, I had the exact same thought when I first viewed the medal reconstruction.

How amazing to see the medal in detail and interesting to read about the necklace which was obviously part of the ‘queens jewels’. I always wondered if Anne had ever worn that necklace.

It’s definitely on my Christmas list!

Beautifully done, and fascinating to hear about the reconstruction process. On a side note, I always thought it interesting that Anne is portrayed as wearing a gable hood in this medal, and it’s even moreso if it’s the same hood Jane Seymour is wearing later on. Of course, clothes were valuable property and there’s nothing especially shocking about them being transferred from one queen to the next, but since Anne is usually portrayed with a French hood it’s still surprising. Perhaps the designers thought that English people would prefer a coin of their queen in English fashions?

Sonetka, I think you are right – Anne was very concious that this. She also chose to wear a gable hood on the day of her execution, when once again she wanted to emphasis her position as the rightful Queen of England.

Wow, Ms. Churchill did a beautiful job! I always wondered what that medallion originally looked like when it was newly struck.

Now we have confirmation, drawn from a source within Anne’s own lifetime, what she really looked like. I wish there were a medallion to be found of Kathryn Howard.

I second Morgan – Ms. Churchill, PLEASE make a pendant sized version of this lovely work available to the world at large!

Anne certainly looks happy in this medal. I remember that she was bearing her second child at that time. And her breasts also showed her condition. A nice recovery!

It’s true Eva, Anne’s breasts were very much emphasised in the medal though previously they had been described as ‘not much raised’. Clearly she wanted to emphasis her femininity and her fecundity :>) It is interesting to note that while Anne is wearing the necklace and gable hood that Jane Seymour later wore, Anne is not wearing the matching dress which was adorned with the same jewel sequence. The dress in the medal has a simply a double row of pearls as a border. Presumably the matching dress was too tight for Anne in her pregnant state :>)

Leslie and Lisa – David Starkey is very much of the same opinion, and he intends to rewrite an earlier article which he wrote with John Rowlands, with reference to this reconstruction of the medal. For the original article, see ‘An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein’s Portrait of Queen Anne Boleyn’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 125, No 959 (Feb 1983) pp88 +90-92

Morgan and Miladyblue – I promise you that I am looking into this possibility as I too would love to be able to wear the Moost Happi medal as a brooch or pendant….It might take some time to achieve, but watch this space… :>)

Hi Lucy,

Thank you for the information, that article was interesting indeed! I anxiously await the revised article that will reference this reconstruction.

The similarities between the medal and sketch are uncanny. I personally don’t agree with the “goiter” theory from the sketch, however. I would like to think that Anne was pregnant with Elizabeth I in this sketch, hence the extra weight/full chin/full busom. This could also be a reason for the familiarity of dress (nightgown, cap, etc) – she was more confined to her chamber while expecting, allowing Holbein to draw her in this condition. That’s just my theory 🙂

She looks just the the Holbein Jane Seymour portrait in the medal! Haha

on a separate portrait note, it always amazed me how much Anne looked like Elizabeth in the NPG famous portrayed that was created after an original in Elizabeth’s reign….then i realized DUH, that may be WHY it looks so much like Elizabeth.

Any insight or thoughts on this?

A lot of people have remarked the similarity between Anne and Elizabeth in portraits.

Based on the depiction of Anne in the medal, they appear to have shared many features, such as the arch of the eyebrow, the high cheekbones and the pronounced chin. This is not surprising given that half of Elizabeth’s genes came from Anne.

However it also makes sense that 50 or 60 years after Anne Boleyn’s death artists would have looked to Elizabeth when depicting her mother. It is highly likely that they did share many features, and to acknowledge this would have double the compliment of the posthumous portrait.

As for the similarity between Anne in the Moost Happi medal and Jane Seymour in Holbein’s portrait, this is understandable given that they are wearing the same costume. However, if you look closely at the two depictions, I think Jane’s stance is not as confident and bold as Anne’s (note the angle of the shoulders and the jut of the chin). It must have been a curious sensation to wear the same gable hood, aware of the recent fate of it’s previous owner.

All I can say Lucy is, WOW…what a labour of love.

You command high praise indeed. You are a true artist.

Thank you :>) Yes, it was a labour of love…nerve-wracking, but full of joy too!

This is brillant! Lucy should feel very proud of herself. She did a great job on restoring this valuable medal of Annes! (By the way i heard that the late joanna denny said that, because Anne is wearing a gable hood, there “is some doubt of authenticity” of the medal.) When reading her biased book i saw what she said about the medal and it really annoyed me! What about you, Claire did it annoy you?

I think this is great news is the medal image of Anne the same as the one from Queen Elizabeths ring that had an image of Anne

Although this post is a couple of years old now I have only just read it in the context of the posts about the Nidd Hall portrait. I was particularly interested in the comments about the jewellery. In particular I was astonished at how Lucy was able to identify the jewels on the billiment of the gable hood. Not only is this jewellery to be seen on portraits of Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Catherine Howard and Catherine Parr but I believe that it is also the jewellery worn by Catherine of Aragon in the circular portrait with the blue background. In that portrait Catherine’s pendant is a jewelled cross such as appears in the “Moost Happi” medal. Is this “the Queen’s jewels” that Henry ordered Catherine to hand over for Anne to wear?

You may well be right Sheila, the jewels that feature in the medal are seen in portraits of Catherine, and Henry’s subsequent wives. Therefore they must have been an important part of the Queen’s (whichever reigned at the time) jewelery collection.

Jaina, Joanna Denny’s strange conclusion is truly bizarre. Contemporary accounts report that Anne wore a gable hood on the morning of her execution. Anne seems to have been very conscious of the power of presentation and chose to wear an English Gable Hood when she wished to stress her legitimacy as the annointed queen of England (for example, on the day of her execution and in this celebratory medallion when she confidently expected to give birth to the next king of England.